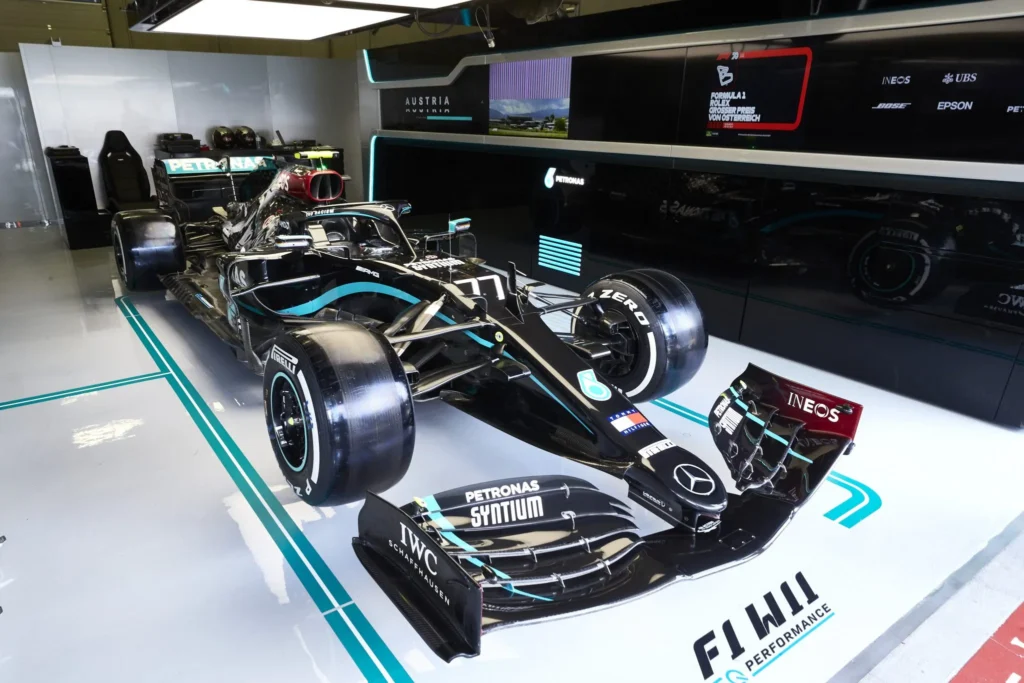

The history of Formula 1 is often written in the margins of the rulebook, defined by moments where engineering ingenuity outpaces regulatory oversight. In February 2020, during the winter testing sessions at the Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya, the Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula One Team unveiled a system that would define the technical narrative of the season: Dual Axis Steering (DAS).

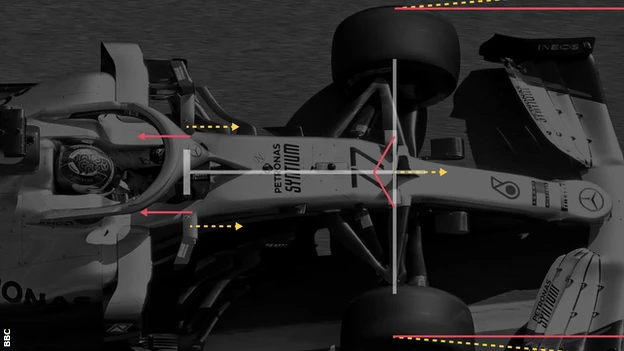

The discovery of DAS was not the result of a press release or a technical briefing. It was uncovered through the vigilance of onlookers and the forensic analysis of onboard camera footage. On the second day of testing, keen-eyed observers noticed a peculiar behavior in the cockpit of Lewis Hamilton’s Mercedes W11. As the six-time World Champion exited the chicane and accelerated onto the main start-finish straight, he did not merely hold the steering wheel steady; he physically pulled the entire steering column toward his chest.

This longitudinal displacement—a movement along the Z-axis of the car, perpendicular to the rotational input required for steering—was immediately flagged as an anomaly. Coinciding with this retraction of the steering column, the front wheels of the W11 were observed to visibly realign. The conventional “toe-out” angle, a staple of racing suspension geometry where the leading edges of the tires point outward, appeared to neutralize, bringing the wheels into a parallel alignment relative to the chassis centerline. As Hamilton approached the braking zone for Turn 1, he pushed the steering wheel forward, returning the column to its standard position and restoring the toe-out required for corner entry.

The revelation sent shockwaves through the paddock. In a sport where suspension geometry is rigidly controlled and active suspension has been banned since 1994, the ability to dynamically alter wheel alignment while the car was in motion appeared, at first glance, to be a flagrant violation of the technical regulations. Yet, the confidence with which Mercedes Technical Director James Allison addressed the media suggested otherwise. When questioned, Allison revealed the system’s name—”Dual Axis Steering”—and casually noted, “This isn’t news to the FIA, it’s something we’ve been talking to them about for some time”.

This report provides an exhaustive engineering analysis of the DAS system. It explores the theoretical physics of tire management that necessitated its creation, the mechanical architecture that made it possible, the fierce regulatory battles that ensued between Mercedes and Red Bull Racing, and the ultimate banning of the device. It serves as a definitive technical retrospective on one of the most audacious innovations in the modern era of Grand Prix racing.

Theoretical Framework: The Physics of Suspension Geometry

To comprehend the magnitude of the DAS innovation, one must first deconstruct the fundamental compromises inherent in open-wheel vehicle dynamics. The DAS system was not designed to make the car faster in a straight line through sheer power; it was a device designed to manipulate the thermal thermodynamic cycle of the Pirelli tires and the aerodynamic drag coefficients of the front axle.

The Compromise of Static Toe Angle

In automotive engineering, “toe” refers to the symmetric angle that each wheel makes with the longitudinal axis of the vehicle.

- Toe-In: The leading edges of the tires point toward each other.

- Toe-Out: The leading edges of the tires point away from each other.

Formula 1 cars almost universally operate with static toe-out on the front axle. This geometric setup is crucial for cornering performance but detrimental to straight-line efficiency.

The Necessity of Toe-Out for Cornering

The primary function of toe-out is to enhance turn-in response and mid-corner stability.

- Yaw Initiation: When a driver initiates a turn, the inside wheel—which is already angled slightly into the turn due to toe-out—creates an immediate yaw moment. This helps “pull” the nose of the car toward the apex, reducing the sensation of understeer and making the car feel more responsive to initial steering inputs.

2. Slip Angle Optimization: As the car loads up laterally in a corner, the outside tire carries the majority of the load. Due to weight transfer and suspension compliance, the wheels naturally undergo dynamic toe changes. Starting with static toe-out ensures that when the car settles into the corner, the loaded outside tire and the unloaded inside tire are operating at optimal slip angles relative to their respective loads.

3. Stability: Toe-out provides a stabilizing effect by creating a “pre-load” on the tires. This prevents the front end from wandering or feeling “nervous” on turn-in, giving the driver confidence to attack the corner entry.

The Penalty of Toe-Out on Straights

While indispensable for the 15-20 corners of a Grand Prix circuit, static toe-out is a parasite on the straights.

- Scrub and Rolling Resistance: Because the wheels are not parallel to the direction of travel, they are constantly “scrubbing” across the asphalt. This lateral friction generates rolling resistance, which manifests as a reduction in top speed and an increase in fuel consumption.

2. Aerodynamic Drag: A wheel angled relative to the airflow presents a larger frontal area and creates a more turbulent wake structure than a wheel aligned parallel to the flow. This turbulence can disturb the airflow downstream, potentially affecting the efficiency of the bargeboards and floor.

3. Thermal Degradation (The Critical Factor): The most significant penalty is thermal. The friction generated by the scrubbing effect creates heat. Specifically, it heats the inner shoulder of the tire tread significantly more than the outer shoulder. This uneven heating creates a thermal gradient across the tire surface. On long straights (like those in Baku, Monza, or Spa), the inner edge of the tire can overheat and blister, while the outer edge cools down below its operating window. This thermal imbalance compromises grip in the subsequent braking zone and shortens the lifespan of the tire compound.

The DAS Solution: Dynamic Optimization

The Dual Axis Steering system was Mercedes’ answer to this century-old compromise. By decoupling the cornering geometry from the straight-line geometry, the W11 could effectively exist in two distinct mechanical states.

Parameter | Conventional F1 Car | Mercedes W11 with DAS |

Cornering State | Toe-Out (Fixed) | Toe-Out (Push Mode) |

Straight-Line State | Toe-Out (Fixed) | Parallel / Zero Toe (Pull Mode) |

Tire Scrub on Straights | High (Inner Edge Wear) | Minimal (Even Wear) |

Front Tire Temperature | Uneven Gradient (Hot Inner / Cold Outer) | Homogenous Distribution |

Aerodynamic Profile | High Drag / Turbulent Wake | Lower Drag / Cleaner Wake |

By pulling the steering wheel, the driver could neutralize the toe-out, aligning the wheels perfectly parallel to the direction of travel. This eliminated the scrub, reduced the drag, and, most importantly, allowed the heat to distribute evenly across the entire width of the tire carcass.

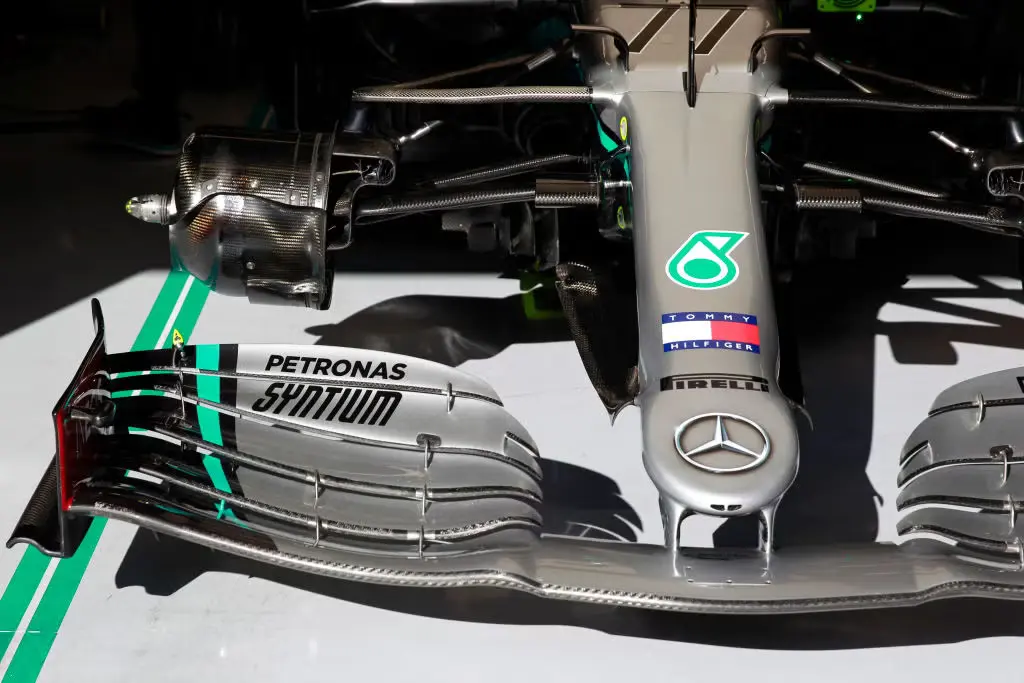

Mechanical Architecture: Inside the W11 Bulkhead

The implementation of DAS required a radical rethinking of the steering assembly. While the concept of variable toe is simple in theory, executing it within the restrictive framework of the FIA Technical Regulations—and within the tight packaging confines of an F1 chassis—was a feat of engineering brilliance.

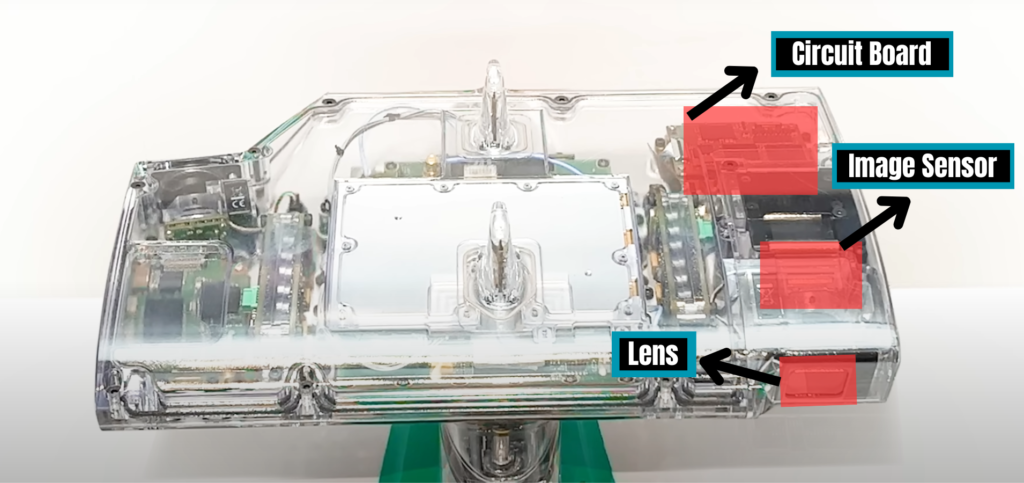

The "Fully Mechanical" Constraint

A critical aspect of the system’s legality was its actuation method. Formula 1 regulations strictly prohibit power-assisted suspension adjustments. Any system that alters the suspension geometry (like toe) must be purely mechanical and operated uniquely by the driver. There could be no electronic motors or programmed actuators managing the transition.

While the W11, like all modern F1 cars, utilized a hydraulic power steering assist to reduce the rotational load on the driver, the DAS mechanism itself had to be initiated by physical displacement. The energy used to alter the wheel alignment came directly from the driver’s muscles pushing and pulling the steering column.

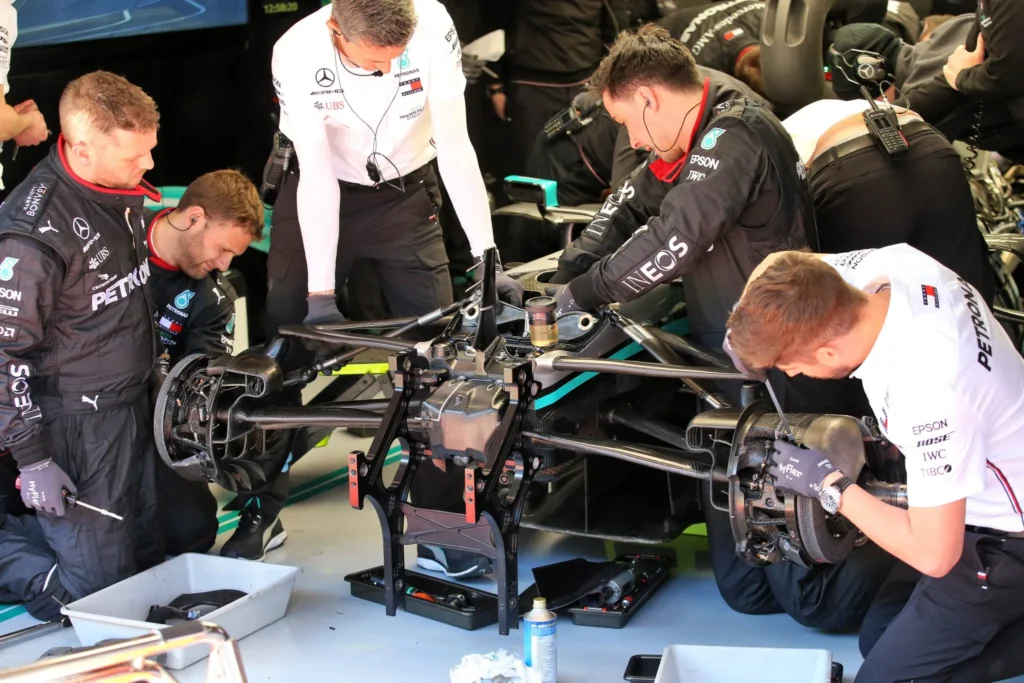

The Actuation Mechanism: Opposing Pinions and Sliding Splines

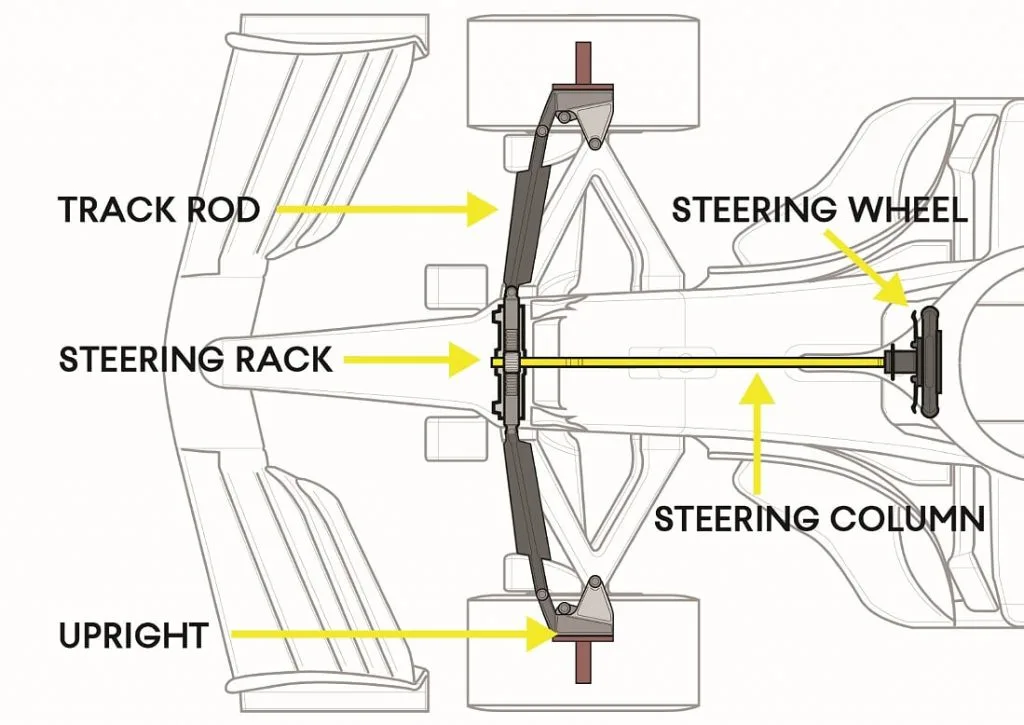

Detailed technical analysis suggests that the DAS system relied on a complex interaction between the steering column and the steering rack.

The Telescopic Column

The steering column of the W11 was modified to allow for longitudinal travel. This required a splined interface that could transmit torque (for turning left and right) while simultaneously sliding axially (for DAS activation). The precision required here was immense; any “play” or looseness in this spline would result in vague steering feel, which is unacceptable to a precision driver like Lewis Hamilton.

The Rack-and-Pinion Interface

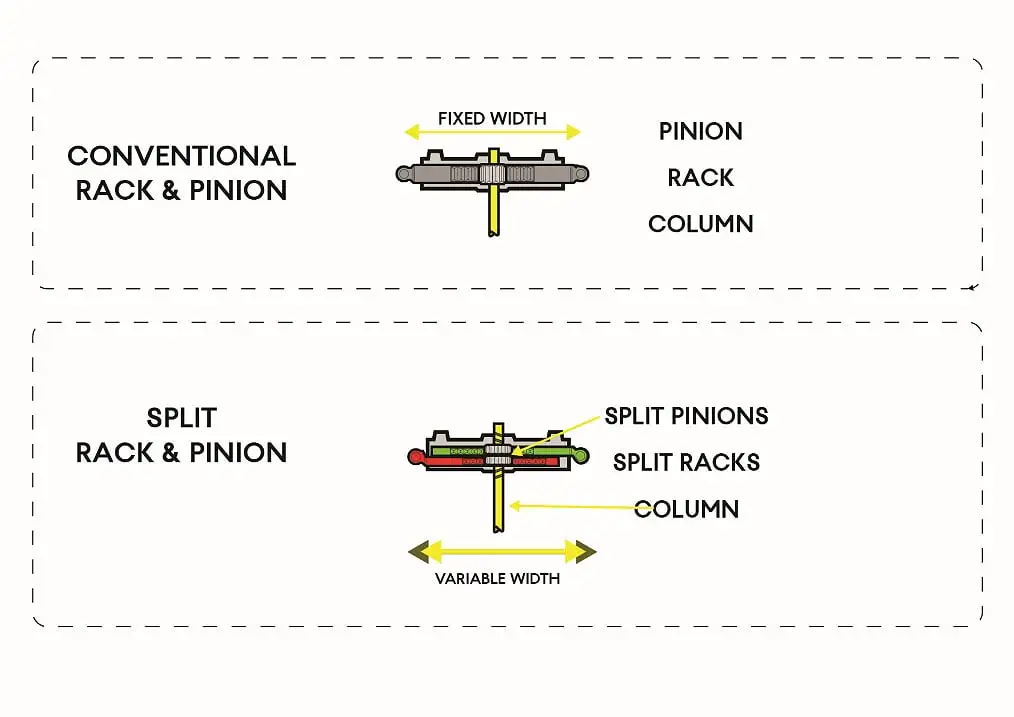

The core of the mechanism likely resided within the steering rack housing. Technical analysts posit the use of a variable rack geometry or an opposing pinion design.

- Standard Operation: In a standard rack, a single pinion gear engages with the rack. Turning the pinion moves the rack left or right.

- DAS Operation: The DAS system likely utilized a mechanism where the longitudinal movement of the column acted upon a secondary lever or a helical gear arrangement. One prevalent theory is that the steering rack was “split” or possessed movable mounting points for the track rods. When the column was pulled back, the mechanism would effectively “shorten” the distance between the inner track rod pivots.

- Geometric Result: Shortening the effective rack length pulls the steering arms inward. Because the track rods connect to the trailing edge of the wheel uprights (in a front-steer configuration) or the leading edge (in a rear-steer configuration), this inward movement alters the toe angle. In the case of the W11, pulling the wheel back reduced the toe-out, bringing the wheels to parallel.

Hydraulic vs. Mechanical Actuation Debate

During the initial discovery, there was significant debate regarding whether the system utilized hydraulic amplification.

- The Hydraulic Hypothesis: Some observers speculated that pulling the steering wheel pressurized a hydraulic master cylinder, which then sent fluid to actuators on the track rods.

- The Mechanical Reality: However, a hydraulic implementation would have faced severe regulatory hurdles. Article 10.2 explicitly bans powered suspension devices. If the hydraulic pressure was generated by a pump, it would be illegal. If it was a closed hydrostatic system (like a brake pedal), it might be legal but heavy.

- Verdict: The consensus, supported by the FIA’s eventual clearance, was that the system was predominantly mechanical. The “monotonic function” requirement in later bans suggests the FIA viewed the DAS input as a direct mechanical linkage. The driver’s physical effort provided the work required to overcome the self-aligning torque of the tires and the friction of the mechanism.

Ackermann Geometry Integration

Beyond simple toe adjustments, the DAS system had profound implications for Ackermann steering geometry.

Ackermann geometry defines the difference in steering angle between the inside and outside wheels during a turn. Ideally, the inside wheel should turn sharper than the outside wheel to trace a smaller radius.

- The F1 Compromise: F1 cars often run “Anti-Ackermann” or parallel steering geometry to maximize the slip angle of the outside tire. This compromises low-speed rotation.

- The DAS Advantage: By having a variable toe system, Mercedes could effectively run a more aggressive Ackermann setup for corners (improving rotation in tight hairpins like Monaco or the final sector at Barcelona) without suffering the drag penalties on the straights. The system allowed them to “reset” the geometry on the fly, optimizing the car for the specific radius of the corner ahead.

Weight and Packaging

The inclusion of DAS was not free. It incurred a weight penalty, estimated to be between 2 kg and 5 kg.

- Placement: This mass was located high in the chassis bulkhead (the steering column assembly), which raises the Center of Gravity (CoG)—a detriment to handling.

- Context: In 2020, Mercedes (and many other teams) were struggling to get down to the minimum weight limit of 746kg. Adding 2-5kg of optional mass was a significant strategic decision.

- Implication: The fact that Mercedes chose to run DAS despite the weight penalty and the CoG disadvantage serves as undeniable proof of the system’s performance value. The lap time gained from better tire usage clearly outweighed the lap time lost from the additional mass.

Thermal Dynamics and Tire Performance Analysis

To fully appreciate why Mercedes invested heavily in DAS, one must look at the data generated by advanced simulation tools. The interaction between the rubber and the road is the single most important variable in Formula 1 performance.

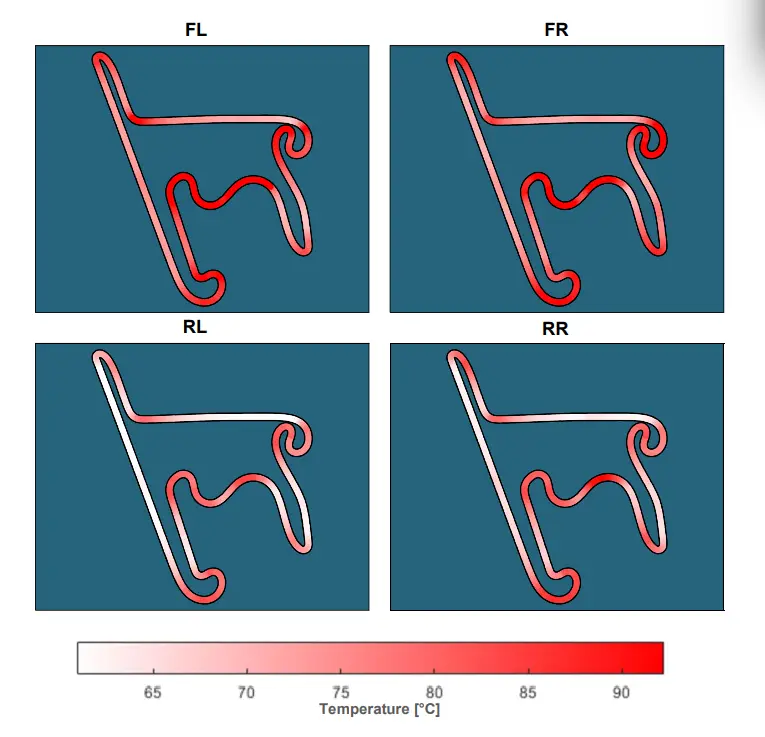

Simulation Data: The RIDEsuite Model

A study utilizing the RIDEsuite multi-physical tire model, co-simulated with a VI-CarRealTime vehicle model, provided a quantitative breakdown of the DAS effect. The simulation modeled a generic Formula 1 vehicle utilizing a DAS control system in a Simulink environment to measure thermal evolution over a race stint.

Friction Power and Slip Angles

The core finding of the simulation was a reduction in friction power. Friction power is the energy dissipated as heat when the tire slides across the track surface.

- Without DAS: The static toe-out creates a constant slip angle even when driving straight. This generates continuous friction power, heating the tire surface.

- With DAS: Activating the system reduces the slip angle to near zero on straights. The simulation confirmed a direct correlation: the decrease in slip angle during DAS activation phases led to a measurable drop in friction power.

Thermal Evolution Results

The analysis showed that DAS led to a lower thermal level in the tires over the course of a stint.

- Heat Rejection: By eliminating the heat generation source on the straights, the tire is able to reject heat to the surrounding air more efficiently. This allows the bulk temperature of the tire to drop, resetting the thermal cycle before the next corner.

- Homogeneity: Crucially, the system prevents the formation of “hot spots” on the inner shoulder. The simulation highlighted that DAS allows the driver to act on the “energetic flux from the contact patch to the whole tire,” optimizing the grip balance.

Strategic Deployment Modes

Telemetry analysis and driver interviews revealed that DAS was not just a “straight-line speed boost” button; it was a versatile thermal management tool used in three distinct scenarios.

Scenario A: The Warm-Up (Qualifying Out-Lap)

Getting heat into the front tires is notoriously difficult for modern F1 cars, especially on smooth tracks or in cool conditions.

- Usage: Drivers were observed pushing and pulling the DAS vigorously on out-laps.

- Mechanism: By rapidly cycling between toe-out and toe-in (or extreme toe-out), the drivers could intentionally induce high levels of scrub. This friction generated heat, waking up the tire carcass and preparing it for the flying lap. James Allison noted that DAS was “very useful in giving us the ability to get some heat into the tyres on out-laps and allow the front to wake up nicely for a qualifying lap”.

Scenario B: The Cool-Down (Race Stint)

This was the primary use case.

- Usage: On main straights during the race.

- Mechanism: Pulling the wheel to parallel alignment reduced scrub, cooling the tires and extending their life. This allowed Mercedes to run softer compounds for longer stints or push harder on the same compound without suffering from thermal degradation or blistering.

Scenario C: Safety Car Restarts

Under Safety Car conditions, tire temperatures plummet, leading to dangerous lack of grip on restarts.

- Usage: Similar to the qualifying out-lap, drivers used DAS to scrub the tires while driving slowly behind the Safety Car. This allowed Hamilton and Bottas to maintain optimal tire temperatures while driving at 80 km/h, giving them a massive grip advantage over rivals when the race restarted.

The Development Timeline: Origins of Innovation

The creation of DAS was not a sudden epiphany but the result of a structured innovation culture within the Mercedes team.

The "Performance Group"

James Allison attributed the idea to the team’s “Performance Group,” a collective of engineers and strategists tasked with identifying areas of the car where performance was theoretically left on the table.

- The Genesis (2018): The concept was first proposed in 2018. The group posed the question: “Would it be possible for us to be able to have the front toe directly steerable by the driver as well as the left-right aspect of the steer?”.

- The Engineering Hurdle: While the aerodynamicists and vehicle dynamicists loved the idea, the mechanical designers initially balked at the complexity. It took two years to refine the mechanism from a concept to a reliable component that could fit inside the cramped front bulkhead of the chassis.

Key Personnel

- James Allison (Technical Director): Allison championed the project, shielding it from cancellation and managing the delicate regulatory dialogue with the FIA. He later described the 2020 version as “relatively crude,” implying that a “DAS 2.0” with finer control was already in the minds of the engineers before the ban.

- John Owen (Chief Designer): Owen was instrumental in the mechanical packaging. The “fizzing mind” of the Chief Designer was credited with solving the spatial puzzle of integrating a sliding steering column into a crash-safety-critical structure.

The Human Element: Ergonomics and Adaptation

The introduction of DAS fundamentally changed the driver’s interaction with the machine. For decades, steering a car had been a two-dimensional task: rotate left, rotate right. DAS introduced a third dimension: the Z-axis push-pull.

The "Unnatural" Sensation

Lewis Hamilton was candid about the strangeness of the system. In interviews, he described the feeling of the steering wheel moving toward him as “weird” and “unnatural”.

- Muscle Memory: Drivers spend thousands of hours conditioning their reflexes. The steering wheel is their primary anchor point in the cockpit. Having that anchor point move, especially under heavy braking forces (up to 5G), required a significant rewiring of their muscle memory.

- Safety Concerns: There were initial concerns about whether the movement would compromise the driver’s control during a crash or sudden snap of oversteer. However, the mechanism was designed to be rigid in the rotational axis regardless of its longitudinal position, ensuring that steering control was never lost.

Driver Workload and Distraction

Valtteri Bottas noted that the team had to learn “whichever situations we think we might get the benefit,” indicating that deployment wasn’t automatic; it required cognitive processing.

- Task Saturation: F1 drivers already manage brake bias, differential settings, engine modes, and radio communications. Adding a manual suspension adjustment on every straight increased the cognitive load.

- Adaptation: Despite the “weirdness,” both drivers adapted quickly. Bottas dismissed the distraction element, joking, “Not that there were so many things to do anyway on the steering wheel,” and called it a “nice little extra tool”. By the Austrian Grand Prix, the movement had become second nature, integrated seamlessly into their lap routines.

The Legal Battlefield: Regulatory Analysis and Protest

The technical brilliance of DAS was matched only by the legal controversy it ignited. The system sat at the precise intersection of two conflicting articles in the FIA Technical Regulations: Article 10 (Suspension) and Article 10.4 (Steering).

The Regulatory Grey Area

The crux of the legality argument revolved around the definition of the system’s primary function.

- Article 10.2 (Suspension Geometry): This regulation explicitly states that “no adjustment may be made to any suspension system while the car is in motion.” Since toe angle is a suspension parameter, changing it dynamically is, prima facie, a breach of Article 10.2.

- Article 10.4 (Steering): This regulation allows for “the realignment of the steered wheels,” provided that this realignment is “uniquely defined by the driver”.

The Mercedes Argument: Mercedes argued that DAS was a steering system, not a suspension system. Since the steering wheel’s primary function is to re-align the front wheels, and DAS re-aligned the front wheels via the steering wheel, it fell under the protection of Article 10.4. The fact that it changed the toe angle was a secondary consequence of steering the wheels.

The Red Bull Argument: Red Bull Racing, led by Christian Horner and Helmut Marko, argued that DAS was a “moveable aerodynamic device” and an illegal active suspension system. They contended that since the primary purpose was to alter the toe (a suspension setting) for thermal and aerodynamic gain, it violated the spirit and letter of Article 10.2.

The Austria 2020 Protest

The tension culminated at the season-opening Austrian Grand Prix in July 2020. After seeing Mercedes use the system in Free Practice 1 and 2, Red Bull lodged a formal protest against the Mercedes W11 cars (specifically Car 77 of Valtteri Bottas and Car 44 of Lewis Hamilton).

The Stewards' Verdict

After hours of deliberation and hearing arguments from both sides, the FIA Stewards rejected the protest, declaring DAS legal for the 2020 season.

The Ruling: The stewards concluded that “the DAS system is physically and functionally a part of the steering system.”

The Logic: They accepted the Mercedes argument that the steering system is allowed to re-align the wheels. They noted that the regulations did not specify that the steering wheel could only rotate. Therefore, the longitudinal movement was a legitimate input method for a steering system.

The Exception: Because it was classified as steering, it benefited from the “implicit exceptions” to the suspension regulations. Essentially, steering is a method of changing suspension geometry (steering angle) that is explicitly allowed. The stewards ruled that DAS fell into this same category.

This decision was a landmark ruling in F1 jurisprudence, confirming that if a mechanism is part of the steering assembly and controlled by the driver, it can legally alter wheel alignment, even if that alteration resembles a suspension setup change.

The Ban: Closing the Loophole

Despite winning the legal battle for 2020, Mercedes lost the war for the future. The FIA moved swiftly to outlaw the device for the 2021 season.

The 2021 Regulatory Amendment

To ban DAS, the FIA did not declare it “illegal” retrospectively; instead, they rewrote the rules to narrow the definition of steering.

- New Article 10.5: The 2021 Technical Regulations introduced a specific clause stating: “The realignment of the steered wheels… must be uniquely defined by a monotonic function of the rotational position of a single steering wheel“.

- The “Smoking Gun” Phrase: By specifying “rotational position,” the FIA explicitly banned any system that relied on sliding, pushing, or pulling. This effectively legislated the sliding steering column out of existence without banning the concept of steering itself.

Rationale for the Ban

The decision to ban DAS was driven by three factors:

- Cost Cap Economics: Formula 1 was entering a new era of financial regulations with the introduction of the budget cap. The FIA feared that if DAS remained legal, every team would be forced to spend millions developing their own versions, triggering a costly arms race that added little value to the spectator experience.

- Safety: While Mercedes had engineered a robust system, the FIA was concerned that other teams, rushing to copy the design mid-season, might produce less safe iterations. A failure in a sliding steering column could be catastrophic.

- Complexity Reduction: The FIA generally seeks to limit driver aids that move the sport toward “active vehicle dynamics.” DAS was seen as a step too far toward active suspension, even if it was manually operated.

Strategic Impact and Competitive Response

The presence of DAS on the W11 had a psychological impact on the grid as potent as its physical one.

The "Copycat" Threat

Following the rejection of their protest, Red Bull openly discussed developing their own DAS system. Christian Horner stated, “Red Bull could roll out its own version if it’s convinced it is legal”.

- The Difficulty: However, copying DAS was not simple. It required a complete redesign of the front bulkhead, steering rack, and suspension geometry. In a condensed season affected by the pandemic, finding the resources to reverse-engineer such a complex system was nearly impossible for rivals.

- The Result: No other team successfully raced a DAS system in 2020. Mercedes enjoyed an exclusive monopoly on the technology for the entire season.

Performance Dominance

The W11 is widely regarded as one of the fastest F1 cars in history. It took pole position in 15 of the 17 races in 2020. While DAS was not the sole reason for this dominance, it was a key contributor to the car’s tire management superiority.

- The Nürburgring Example: At the Eifel Grand Prix, cold conditions made tire warm-up critical. While rivals struggled with graining and lack of grip, the Mercedes drivers used DAS to generate heat on the formation lap, maintaining their advantage into Turn 1.

Legacy: DAS in the Hall of Fame

The Dual Axis Steering system takes its place alongside the sport’s most legendary innovations—devices that were legal for a brief, shining moment before being legislated into history.

Comparative Innovations

- The Brabham BT46B “Fan Car” (1978): Like DAS, the Fan Car exploited a definitional loophole (arguing the fan was for cooling, not downforce). It was banned after one race.

- The McLaren F-Duct (2010): Like DAS, the F-Duct required “unnatural” driver intervention (using a knee or hand to cover a hole in the cockpit) to stall the rear wing and reduce drag. It was banned the following year.

- The Tyrrell P34 Six-Wheeler (1976): A radical mechanical departure designed to reduce drag, similar to the drag-reduction goals of DAS.

The Mercedes Statement

Ultimately, DAS served as a declaration of engineering supremacy. At the height of their dominance, Mercedes did not play it safe. They authorized a high-risk, expensive, and complex R&D project to gain a marginal advantage. As James Allison reflected, the system was “a very unusual” product of a team culture that encourages engineers to ask, “What if?”.

The image of Lewis Hamilton pulling the steering wheel on the straights of Barcelona remains the defining visual of the W11—a machine that was not just faster than its rivals, but smarter. DAS proved that even in an era of stifling regulations, the grey areas of the rulebook remain fertile ground for those bold enough to explore them.

Great Post.