In the hyper-regulated, high-velocity ecosystem of Formula 1, the Safety Car serves as the ultimate arbiter of track safety, a dynamic regulatory instrument that bridges the gap between full-course racing and race suspension. Far more than a mere vehicle, the Safety Car is a mobile command center, a high-performance track weapon, and a strategic variable that can alter the outcome of World Championships. Its role is paradoxical: it must neutralize the race to ensure safety while maintaining a velocity high enough—often exceeding 280 km/h—to preserve the operational integrity of the delicate, temperature-sensitive machines trailing in its wake.

This report provides a comprehensive examination of the Formula 1 Safety Car, tracing its evolution from the chaotic ad-hoc deployments of the 1970s to the integrated, dual-manufacturer fleet of the modern era. It analyzes the mechanical specifications of the current Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series and Aston Martin Vantage, dissects the onboard telemetry and marshalling systems provided by EM Motorsport, and details the complex regulatory frameworks governing its deployment, including the controversial unlapping procedures reformed post-2021. Furthermore, it explores the human factors of the permanent driver and co-driver team, and the strategic ripple effects—thermodynamic and mathematical—that deployment imposes on race strategies.

Historical Genesis: The Evolution of On-Track Control

The history of the Safety Car is a reflection of Formula 1’s broader journey from a dangerous, loosely organized amateur sport to a data-driven, safety-obsessed professional discipline. The concept of a “Pace Car,” borrowed from North American oval racing, was initially viewed with skepticism in Europe, leading to a fragmented adoption process characterized by inconsistency and, occasionally, farce.

The Chaotic Debut: Mosport Park 1973

The genesis of the Safety Car in Formula 1 is traced to the 1973 Canadian Grand Prix at Mosport Park. The race was conducted under torrential conditions, with heavy rain rendering the undulating track treacherous. Following a collision involving François Cevert and Jody Scheckter, race officials made the unprecedented decision to deploy a vehicle to neutralize the field rather than stopping the race entirely.

The vehicle chosen was a yellow Porsche 914, a mid-engined sports car that, while nimble, lacked the presence and performance of modern safety vehicles.1 It was piloted by Eppie Wietzes, a former Canadian racing driver. The deployment, however, was marred by a lack of established protocol and communication infrastructure. Without radio contact with the grid or clear instructions from timekeepers, Wietzes entered the track and positioned the Porsche in front of the wrong car—Howden Ganley’s Iso-Marlboro—mistaking it for the race leader, Jackie Stewart.

This error had catastrophic consequences for the race’s sporting integrity. By picking up a mid-pack runner, the Safety Car inadvertently allowed the true leaders to gain nearly a full lap on the rest of the field, while trapping other drivers a lap down. The confusion was absolute; the manual lap charts were thrown into disarray, and it took several hours after the checkered flag for officials to reconstruct the race order and confirm Peter Revson as the winner. This chaotic debut highlighted the inherent dangers of deploying a control vehicle without a robust regulatory framework and solidified the sport’s resistance to the concept for nearly two decades.

The Wilderness Years and the "Oddities" (1974–1992)

Following the 1973 debacle, the Safety Car concept was largely abandoned in favor of traditional flag signals. However, the need for a course car remained, leading to a period where local circuit organizers were responsible for providing a vehicle. This resulted in a bizarre and inconsistent array of machinery, ranging from exotic supercars to mundane family sedans, with no standardization in performance or equipment.

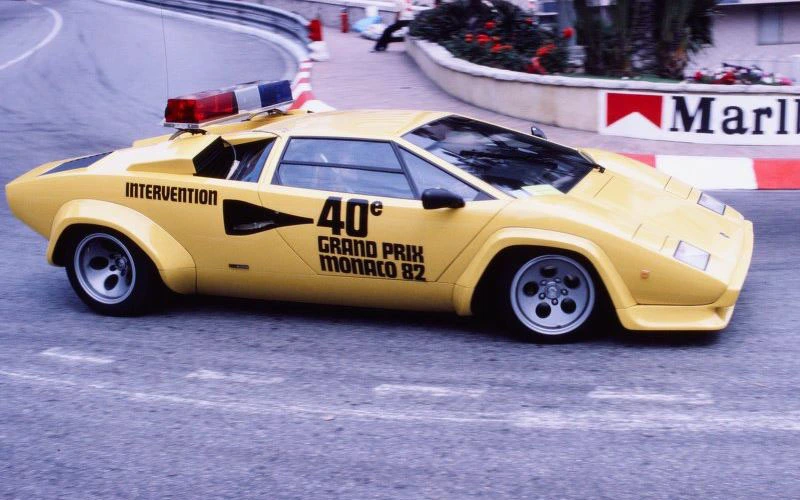

The Monaco Era (1981–1983)

The glamour of the Monaco Grand Prix demanded a vehicle that matched the spectacle of the principality. During the early 1980s, the Automobile Club de Monaco utilized a Lamborghini Countach as the intervention vehicle. With its scissor doors and V12 engine, the Countach was visually arresting but operationally flawed; its poor rearward visibility and difficult clutch made it a challenging tool for the stop-start nature of safety car duty.

The Eastern Bloc Experiment: Tatra 613

Perhaps the most unusual vehicle to ever grace the F1 grid was the Tatra 613 (specifically the T-623 R rapid response version), used at the Hungarian Grand Prix. This Czechoslovakian luxury sedan featured an air-cooled, rear-mounted 3.5-liter V8 engine. While it possessed a certain utilitarian ruggedness and a top speed of 230 km/h, the sight of a heavy, rolling limousine leading high-tech F1 cars remains one of the sport’s most incongruous images.

The Low Point: Imola 1994 and the Opel Vectra

The inconsistency of the “local supply” model had tragic implications. At the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, a standard Opel Vectra was deployed following a start-line accident involving Pedro Lamy and JJ Lehto. The Vectra, a mass-market sedan, was woefully underpowered for the task. The race leader, Ayrton Senna, famously pulled alongside the Safety Car, gesticulating frantically for the driver to increase speed. The Vectra’s inability to maintain a sufficient pace caused the tire pressures of the trailing F1 cars to drop critically, reducing ride height and grip. While the subsequent fatal accident of Senna was multifaceted, the loss of tire pressure behind the slow Safety Car is frequently cited as a contributing factor to the car’s instability. This tragedy was a catalyst for the complete overhaul of F1 safety procedures.

Standardization and the Mercedes Partnership (1996–Present)

Recognizing the critical need for a high-performance, standardized vehicle driven by a professional, the FIA established a formal long-term partnership with Mercedes-Benz in 1996.1 This agreement ensured that a suitable AMG-tuned vehicle would be available at every round of the championship, ending the era of “local oddities.”

- 1996: The Mercedes-Benz C36 AMG becomes the first official permanent Safety Car.

- 1997–1999: The CLK 55 AMG takes over, introducing greater power and coupe dynamics.

- 2000: Bernd Mayländer is appointed as the official driver, bringing professional racing experience to the cockpit.

- 2010–2014: The SLS AMG brings supercar performance, with its “Gullwing” doors becoming iconic.

- 2015–2017: The AMG GT S introduces the modern twin-turbo V8 platform.

- 2018–2021: The AMG GT R raises the bar with active aerodynamics and track-focused suspension.

In 2021, the monopoly evolved into a duality with the entry of Aston Martin, marking the first time in 25 years that two manufacturers shared the duty, reflecting the British brand’s return to Formula 1.

Technical Anatomy: The Modern Safety Car Fleet

The modern Safety Car is not a standard road vehicle with a light bar; it is a highly modified track specialist, engineered to withstand the extreme duty cycle of leading F1 cars. It must be capable of “cold start” performance—launching from a standstill at the pit exit directly into race pace—and sustaining high speeds without overheating its engine, transmission, or brakes.

The Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series (2022–Present)

The current Mercedes representative is the AMG GT Black Series, a machine that blurs the line between road car and GT3 racer. It represents the pinnacle of the Safety Car’s technical evolution.

Powertrain: The Flat-Plane V8

At the core of the Black Series is the M178 LS2 engine, a handcrafted 4.0-liter V8 biturbo unit. Unlike standard AMG engines which use a cross-plane crankshaft, this engine utilizes a flat-plane crankshaft. In a flat-plane configuration, the crank pins are arranged at 180-degree intervals, creating a firing order that oscillates between cylinder banks (1-8-2-7-4-5-3-6).

- Gas Dynamics: This design improves the gas cycle, allowing for more uniform exhaust pulses and significantly sharper throttle response—crucial for the Safety Car driver when modulating the pace to control the F1 pack.

- Performance Figures: The engine produces 730 hp (537 kW) at 6,700–6,900 rpm and 800 Nm of torque. This propels the car from 0 to 100 km/h in 3.2 seconds and to a top speed of 325 km/h.

- Transmission: Power is delivered via an AMG SPEEDSHIFT DCT 7-speed dual-clutch transaxle located at the rear axle for optimal weight distribution.

Aerodynamics: The "Light Bar Delete"

The most significant innovation of the Black Series Safety Car is the removal of the traditional roof-mounted light bar. Extensive wind tunnel testing revealed that the massive rear wing of the Black Series—essential for generating the 400 kg of downforce required for high cornering speeds—would be aerodynamically compromised by the turbulence from a roof bar.

- Integrated Signaling: To solve this, engineers integrated the signaling lights directly into the vehicle’s bodywork.

- Front: LED signaling modules are embedded into the top of the windscreen, level with the sun visors.

- Rear: The main upper blade of the rear spoiler houses 13 orange LEDs (for “No Overtaking”) and 4 green LEDs (for “Overtaking Allowed”).

- Side: Small light modules in the rear side windows display “SC” in orange to alert spectators.

This integration ensures that the airflow to the rear wing remains laminar, preserving the car’s aerodynamic balance.

Chassis and Suspension

The car features the AMG Track Package as standard, which includes a bolted titanium roll cage for driver protection and increased chassis rigidity. The suspension is a manually adjustable coil-over system with variable preload, allowing the setup to be tailored to specific circuits (e.g., maximizing ride height for the curbs of Singapore vs. stiffening for the smooth asphalt of Paul Ricard). Ceramic high-performance compound brake systems are fitted to handle the immense thermal loads of repeated high-speed stops.

The Aston Martin Vantage F1 Edition (2021–Present)

Sharing the calendar is the Aston Martin Vantage, specifically a modified version that spawned the “F1 Edition” road car. While distinct from the Mercedes, it follows the same philosophy of track-focused optimization.

Powertrain and Performance

The Vantage utilizes a variant of the 4.0-liter twin-turbo V8 (supplied by Mercedes-AMG).

- 2024 Upgrades: For the 2024 season, the Vantage received a substantial update, with power increased by 30% to 665 PS (656 hp) and torque to 800 Nm. This power hike was achieved through modified cam profiles, optimized compression ratios, and larger turbochargers.

- Cooling: The cooling system features additional vents and a reconfigured radiator setup to manage engine temperatures during the “stop-start” cycle of waiting in the pit lane and then sprinting at full throttle.

- Acceleration: The car is capable of 0–60 mph in 3.4 seconds.

Aerodynamics: The Aero-Plinth

Unlike the Mercedes, the Aston Martin retains a roof-mounted light bar. However, it is a bespoke aerodynamic design. The light bar is mounted on a carbon fiber plinth that is raised above the roofline. The profile of the plinth is sculpted to direct airflow cleanly over the bar and toward the rear wing, minimizing the drag penalty typically associated with such appendages.

- Downforce: The car features a unique front splitter and vaned grille, along with a revised rear wing, generating 155.6 kg of downforce at 200 km/h—significantly higher than the standard production model.

Comparative Technical Specifications

Specification | Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series | Aston Martin Vantage (2024 Spec) |

Engine Configuration | 4.0L V8 Biturbo (Flat-Plane Crank) | 4.0L V8 Twin-Turbo |

Power Output | 730 hp (537 kW) | 665 PS (656 hp) |

Torque | 800 Nm | 800 Nm |

Transmission | 7-Speed DCT Transaxle | 8-Speed ZF Automatic |

0-100 km/h (0-62 mph) | 3.2 seconds | ~3.5 seconds |

Top Speed | 325 km/h (202 mph) | 325 km/h (202 mph) |

Aerodynamics | Active Aero, Integrated Lights | Fixed Aero, Aero-Plinth Light Bar |

Signaling System | Windscreen & Wing Integrated LEDs | Roof-Mounted Aero Light Bar |

Downforce @ 200 km/h | ~400 kg+ (at 250km/h) | ~155.6 kg |

Weight | ~1,520 kg (DIN) | ~1,570 kg |

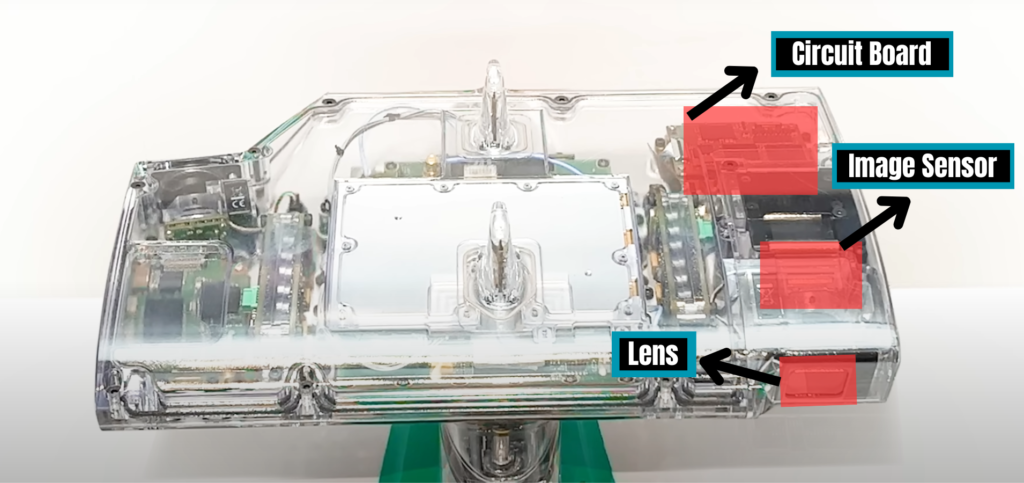

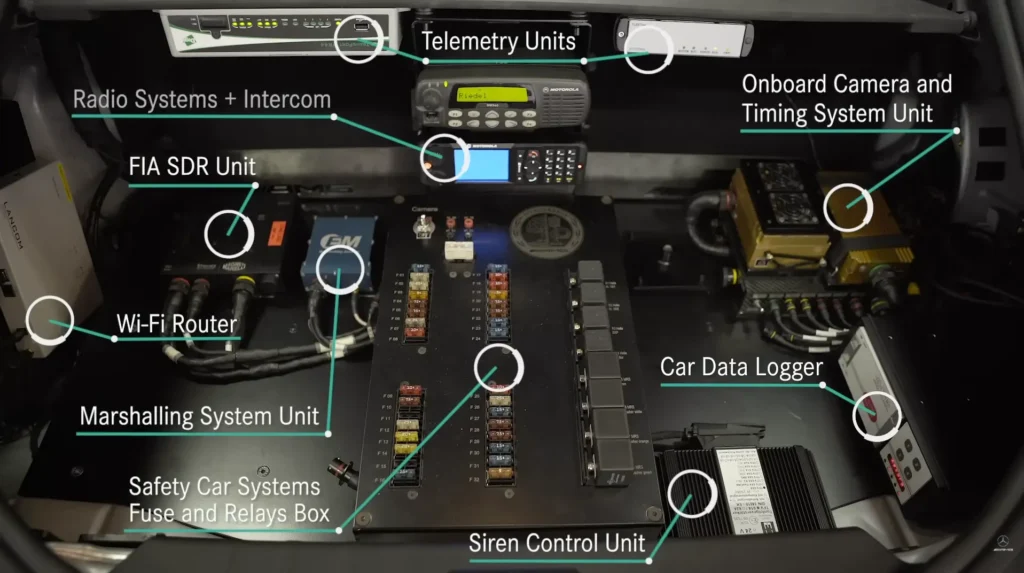

The Nerve Center: Onboard Technology and Telemetry

The interior of the Safety Car functions as a high-tech control room. While the exterior screams “race car,” the interior is dominated by the sophisticated electronic systems required to monitor the race and communicate with Race Control.

The "Office" Configuration

The standard production seats are replaced by FIA-approved racing bucket seats equipped with six-point harnesses to secure the occupants under high G-loads. The cockpit layout is designed to split responsibilities between the driver (driving) and the co-driver (operations).

- Monitor 1 (Left): This screen displays the international TV broadcast feed. This allows the co-driver to see what the television audience and Race Control are seeing—crucial for understanding the context of an accident (e.g., seeing a replay of a crash to determine if debris is scattered across the track).

- Monitor 2 (Right): This screen displays the “Timing and Scoring” page and a dynamic track map. The GPS positions of every car on the track are visualized in real-time, allowing the co-driver to identify the race leader, monitor the gaps between cars, and pinpoint the exact location of a hazard.

- “Always On” Rear View: Regardless of the rear wing’s obstruction, a high-definition digital rear-view mirror is fed by cameras mounted on the rear of the car. This provides the crew with a crisp view of the F1 cars queuing behind them, essential for judging the restart pace.

The F1 Marshalling System (F1MS)

Supplied by EM Motorsport, the F1 Marshalling System is the digital backbone of the Safety Car’s operation.

- Bi-Directional Telemetry: The system does not just receive data; it sends it. It transmits the Safety Car’s precise GPS coordinates to Race Control and to the F1 teams.

- Flag Management: The co-driver can verify the status of the digital flag panels around the circuit. The system allows the Safety Car to trigger the “SC” mode on the steering wheel displays of all 20 F1 cars simultaneously.

- G-Force Alerts: The car is linked to the medical warning system. If an F1 car experiences an impact exceeding a certain threshold (typically roughly 20G), a medical warning light flashes in the Safety Car cockpit, alerting the crew that the Medical Car (which follows the pack on the opening lap) may be required.

Connectivity and Isolation

The Safety Car utilizes a high-redundancy radio system to maintain constant voice contact with the Race Director. Crucially, the telemetry systems of the Safety Car are electrically isolated from the car’s control electronics (ECU), except for essential power and synchronization links. This ensures that the sensitive data acquisition systems do not interfere with the car’s mechanical operation—a fail-safe to prevent an electronic glitch from stalling the Safety Car in front of the pack.

The Human Element: Mayländer and Darker

The operation of the Safety Car relies on the symbiotic relationship between its two occupants: the driver, Bernd Mayländer, and the co-driver, Richard Darker.

Bernd Mayländer: The Permanent Driver

Since 2000, Bernd Mayländer has served as the official Safety Car driver for nearly every Grand Prix. A former DTM racer, Mayländer possesses a unique skillset. He is not racing to win; he is racing to maintain a specific delta.

- The “Slow” Illusion: To the external observer—and often to the F1 drivers behind him—the Safety Car appears slow. Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen frequently complain over the radio about the pace. However, Mayländer is typically driving at 98-99% of the car’s limit, often sliding through corners and attacking curbs. The perception of slowness arises from the immense performance gap: an F1 car generates so much downforce that its cornering speed is vastly higher than even the most advanced GT car.

- Routine: Mayländer’s weekend begins on Thursday with track inspections and system checks. He participates in the Drivers’ Briefing to discuss specific safety concerns. On race day, he is strapped into the car at the end of the pit lane well before the race start, ready to deploy instantly.

Richard Darker: The Co-Driver

Richard Darker acts as the navigator and operational officer. His role is to free Mayländer to focus entirely on driving.

- The Spotter: Darker constantly monitors the GPS tracker to inform Mayländer of the approaching race leader. “Leader is Verstappen, 10 seconds behind, catching fast.”

- The Operator: He physically operates the light panel switches (Orange to Green) and manages the radio communication with Race Control.

- The Second Pair of Eyes: When approaching an accident scene, Darker scans the track for debris or marshals that Mayländer might miss while focusing on the apex.

Regulatory Framework: Rules of Engagement

The deployment and conduct of the Safety Car are governed by Article 55 of the FIA Formula 1 Sporting Regulations (previously Article 40). These rules are rigid, designed to eliminate ambiguity during high-stress interventions.

Deployment Triggers and Procedures

The Safety Car is deployed under the authority of the Clerk of the Course (often at the direction of the Race Director) when:

- There is an immediate hazard to competitors or officials (e.g., a stopped car on the racing line).

- Weather conditions render the track unsafe for full-speed racing (e.g., standing water causing aquaplaning).

- Debris covers a large section of the track, requiring marshals to enter the surface.

The Pick-Up: Upon deployment, the message “SAFETY CAR DEPLOYED” flashes on official monitors. The Safety Car departs the pits with orange lights flashing. Its objective is to pick up the race leader. If it enters the track ahead of a mid-pack car, it will display green lights to signal that car to pass, waving cars through until the race leader is behind it.

The "No Overtaking" Rule

From the moment the “Safety Car Deployed” message is sent, overtaking is strictly prohibited across the entire circuit (unless a driver is signaled to do so by the Safety Car). Drivers must reduce speed and stay above a minimum time set by the ECU—the “delta time”—until they join the line behind the Safety Car.

The Unlapping Controversy and 2022 Reform

The procedure for handling “lapped cars” (cars that have been passed by the leader) became the center of a global sporting controversy at the 2021 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix.

- The Issue: Lapped cars physically sitting between the first and second place drivers prevent a direct race at the restart. Historically, the rules allowed these cars to unlap themselves (pass the SC and rejoin the back of the queue) to “clean up” the grid.

- 2021 Incident: Race Director Michael Masi allowed only the five lapped cars between Hamilton and Verstappen to unlap themselves, and then restarted the race immediately, contrary to the regulation that required an additional lap.

- The Reform (2022): Following an FIA inquiry, the rules were tightened.

- “All” vs. “Any”: The regulation was clarified to ensure that if unlapping is permitted, “all” lapped cars must do so, removing ambiguity.

- Automated Procedure: The Safety Car will now return to the pits at the end of the following lap after the message “LAPPED CARS MAY NOW OVERTAKE” is sent. This decouples the restart from the physical position of the unlapping cars, speeding up the restart process while ensuring procedural consistency.

The Restart Phase

When the track is clear, the message “SAFETY CAR IN THIS LAP” is displayed.

- Lights Out: The Safety Car extinguishes its orange lights. This is the visual signal to the race leader that they now control the pace.

- The Drop: The Safety Car accelerates away from the pack to enter the pits. It must cross Safety Car Line 1 (Pit Entry) before the race leader does, ensuring it does not impede the race start.

- The Control Line: Drivers may not overtake the car ahead of them until they cross the “Control Line” (the Start/Finish line). This prevents drivers from jumping the restart before the official lap begins.

The Virtual Safety Car (VSC)

The Virtual Safety Car (VSC) was introduced in 2015 as a direct response to the accident of Jules Bianchi at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix. It is a system designed to neutralize a race quickly without the disruption of a physical Safety Car.

Mechanics of the VSC

Unlike the physical SC, the VSC does not bunch the field together. It essentially freezes the gaps between cars by imposing a speed limit on the entire track.

- The 30-40% Reduction: Drivers are required to reduce their speed by approximately 30-40% compared to a dry race lap.

- The Dashboard Delta: The driver’s steering wheel displays a “Delta” time.

- A Positive Delta (+) means the driver is slower than the reference time (Safe).

- A Negative Delta (-) means the driver is faster than the reference time (Violation).

- Marshalling Sectors: The track is divided into 50-meter “marshalling sectors.” Drivers must maintain a positive delta at least once inside every single sector, preventing them from speeding in one section and slowing in another to “game” the system.

Strategic Implications: The Chaos Factor

The deployment of the Safety Car (SC) or VSC is the single most disruptive variable in race strategy. It creates opportunities for “cheap” pit stops and resets the competitive order.

The "Cheap" Pit Stop

Under green flag conditions, a pit stop costs a driver roughly 20–25 seconds of race time (the time spent in the pit lane relative to cars moving at full speed on track).

- SC/VSC Effect: Under the SC or VSC, the cars on track are moving much slower. Therefore, the time lost relative to them while stationary is significantly reduced—often to just 10–12 seconds.

- Strategy: Teams will often instruct a driver to “extend” a stint, keeping them on old tires in the hope that a Safety Car will be deployed, gifting them a pit stop that costs half as much time as their rivals.

Tire Thermodynamics and Hysteresis

The most critical physical challenge during a Safety Car period is tire temperature. F1 tires (Pirelli) are designed to operate in a window roughly between 100°C and 110°C.

- Cooling Danger: At Safety Car speeds, tire temperatures plummet. Rubber exhibits a property called viscoelastic hysteresis: warm rubber is soft and sticky; cold rubber is hard and brittle.

- The Restart Struggle: A driver on “Hard” compound tires (which are harder to warm up) is at a massive disadvantage at a restart against a driver on “Soft” tires. The car on cold tires will lack mechanical grip, leading to wheelspin and sliding. This thermodynamic reality was the deciding factor in the 2021 Championship: Hamilton (on old, cold Hards) was physically unable to defend against Verstappen (on fresh Softs) because his tires could not generate the necessary friction coefficient.

Conclusion

The Formula 1 Safety Car has evolved from a Porsche 914 causing confusion in the rain to a technological tour de force that underpins the integrity of the sport. The modern Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series and Aston Martin Vantage are not merely marketing exercises; they are essential safety tools, equipped with the telemetry, aerodynamics, and performance required to lead the fastest racing cars on Earth.

Through the symbiotic work of Bernd Mayländer and Richard Darker, and the rigorous application of FIA regulations, the Safety Car ensures that when the unpredictable happens—be it a crash, a deluge, or debris—the sport can pause, reset, and resume safely. It is the guardian of the grid, a machine that must be fast enough to keep the show on the road, yet controlled enough to save lives. As Formula 1 continues to push the boundaries of speed, the Safety Car will inevitably evolve with it, remaining the indispensable keystone of Grand Prix racing.

Technical Appendix

Safety Car Technical Comparison (2024 Specs)

Feature | Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series | Aston Martin Vantage F1 Edition (2024) |

Engine | 4.0L V8 Biturbo (Flat-plane crank) | 4.0L V8 Twin-Turbo |

Power Output | 730 hp (537 kW) | 665 PS (656 hp) |

Torque | 800 Nm | 800 Nm |

0-100 km/h | 3.2 seconds | 3.4 seconds |

Top Speed | 325 km/h (202 mph) | 325 km/h (202 mph) |

Light System | Integrated (Windscreen/Wing) | Roof-mounted Aerodynamic Bar |

Aerodynamics | Active Aero, 400kg+ downforce | Fixed Aero, Extended Splitter/Wing |

Weight | ~1,520 kg (DIN) | ~1,570 kg |

Table 2: Key Historical Milestones

Year | Event | Vehicle | Significance |

1973 | Canadian GP | Porsche 914 | First deployment; caused chaos with incorrect pick-up. |

1981 | Monaco GP | Lamborghini Countach | Introduction of exotic supercars; defined “glamour” era. |

1993 | Brazilian GP | Fiat Tempra | Official formalization of the Safety Car rule (Article 40). |

1996 | Belgian GP | Mercedes C36 AMG | Start of the exclusive Mercedes supply contract. |

2000 | Australian GP | Mercedes CL55 AMG | Bernd Mayländer begins his tenure as permanent driver. |

2010 | Bahrain GP | Mercedes SLS AMG | Introduction of the “Gullwing” era; massive performance jump. |

2015 | Various | (Virtual Safety Car) | VSC system introduced following Jules Bianchi’s accident. |

2021 | Bahrain GP | Aston Martin Vantage | End of Mercedes monopoly; shared supply duties begins. |

2022 | Bahrain GP | Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series | First SC without a roof bar; integrated signaling lights. |