The inaugural decade of the Formula 1 World Championship (1950–1959) represents a unique and volatile epoch in motorsport history. It was a period defined not by radical breakthroughs at its inception, but by the relentless, necessary application of sophisticated post-war engineering principles to antiquated Grand Prix concepts. Born from the rubble of World War II, F1 began as a stopgap measure utilizing existing machinery, yet by 1959, the fundamental technical template of the modern racing car had been forged and proven, setting the stage for the aerospace-driven design revolution of the 1960s.

The Genesis of Grand Prix: Starting from the Rubble (1950–1953)

The formalization of the World Championship in 1950 was directly facilitated by the geopolitical and economic consequences of the recent global conflict. The dominant forces of pre-war Grand Prix racing—the formidable German Silver Arrows of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union—were effectively sidelined. Germany was banned from international competition until 1950 due to post-war sanctions, and its manufacturing infrastructure was crippled. Mercedes-Benz faced the immense task of rebuilding its operations in a shattered economy, while the fate of Auto Union was even worse, with its factories in East Germany seized and the company largely dismantled by the Red Army. This technological vacuum provided a rare opportunity for other nations to step forward.

The revival of top-tier single-seater racing was spearheaded by Italy and France. The rules for the newly formalized championship—initially known as Formula A and officially dubbed Formula 1 by the FIA in 1950—were a continuation of pre-war Grand Prix specifications: 4.5 litres for naturally aspirated (NA) engines or 1.5 litres for supercharged (SC) engines. The early years of the championship were thus defined by the reliance on optimized pre-war designs.

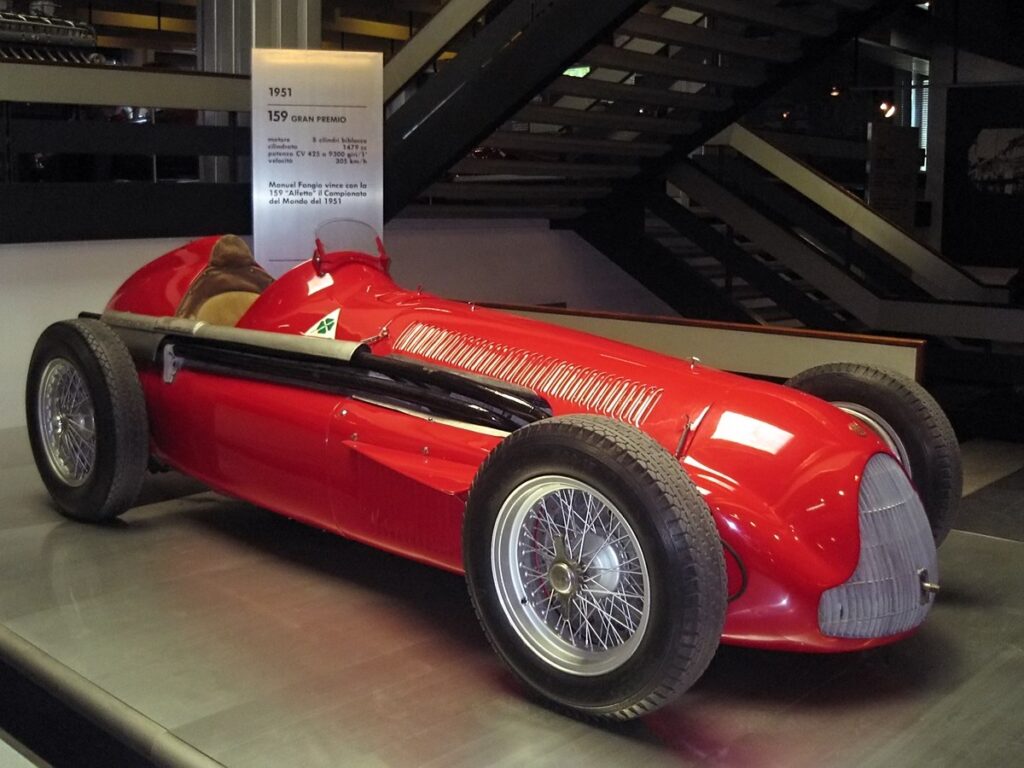

The defining machine of this initial era was the Alfa Romeo 158. This 1.5-litre supercharged marvel, which achieved championship success, was originally designed for the smaller and lighter voiturette category. The fact that a scaled-down design dominated the highest echelon of motorsport speaks volumes about the early technological landscape. The power output, although impressive for the time (some specialized SC engines reached 600 horsepower by 1953 in related series), was contained within a physically simple, pre-war style machine that typically relied on a ladder chassis and basic suspension.

The championship’s initial reliance on existing inventory meant that the earliest years of F1 prioritized reliability and the optimization of proven, if structurally rudimentary, technology rather than genuine innovation. This reliance was cemented by the economic realities of the time; in 1952 and 1953, the World Drivers’ Championship was actually contested under the less expensive Formula Two regulations, rather than the intended Formula 1 rules, further delaying the commitment of resources needed for radical F1-specific engineering development. The true catalyst for modern F1 innovation would not arrive until the regulatory reset in 1954, which coincided with the full industrial return of Germany.

The Structural Revolution: Chassis, Metallurgy, and Aerodynamics (1954–1955)

The 1954 season marked the true beginning of high-stakes technological competition in Formula 1. The FIA introduced a major regulatory reset, significantly reducing engine size. Naturally aspirated capacity was cut to 2.5 litres, while supercharged cars were limited to a tiny 750 cc. This effectively standardized the sport around the 2.5L NA format (producing around 290 hp) and ended the competitive viability of the high-strung, fuel-hungry supercharged engines for the World Championship.

This reset was perfectly timed for the return of Mercedes-Benz. The German manufacturer re-entered Grand Prix racing with the W196, a machine that immediately rendered much of the existing grid obsolete by introducing structural and mechanical sophistication derived directly from high-end, post-war research and development.

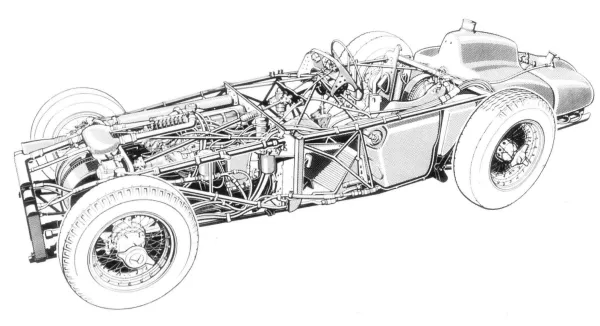

The Rise of the Spaceframe

The most critical departure from previous design philosophy was the W196’s use of the Tubular Spaceframe chassis. Up to this point, most cars relied on the heavy, robust, pre-war Ladder Chassis—a design consisting of two thick longitudinal rails connected by cross-braces, primarily valued for its simplicity and robustness, characteristics suitable for heavy load-bearing vehicles like trucks and early commercial cars.

In contrast, the spaceframe, derived from techniques developed in aerospace engineering during and immediately after World War II, utilized numerous small, triangulated tubes to create a complex, rigid, three-dimensional structure. The engineers abandoned the idea of simple durability (robustness) in favor of maximized dynamic performance (rigidity). This design provided a vastly superior strength-to-weight ratio, meaning the chassis was much lighter while offering superior torsional stiffness.

This enhanced rigidity was crucial, as it allowed the W196’s suspension components to work precisely as designed, transforming handling predictability and driver feedback—a precision that heavier, flexing ladder chassis could never achieve. Furthermore, Mercedes employed lightweight materials like Elektron magnesium-alloy for the bodywork, underscoring the direct transfer of lightweight material science from military and aircraft applications into elite motorsport. The eight-cylinder inline engine was mounted at a severe 53-degree angle within the spaceframe, lowering the car’s center of gravity and optimizing weight distribution—a radical step forward in vehicle dynamics.

Table 1: 1950s Grand Prix Chassis Comparison

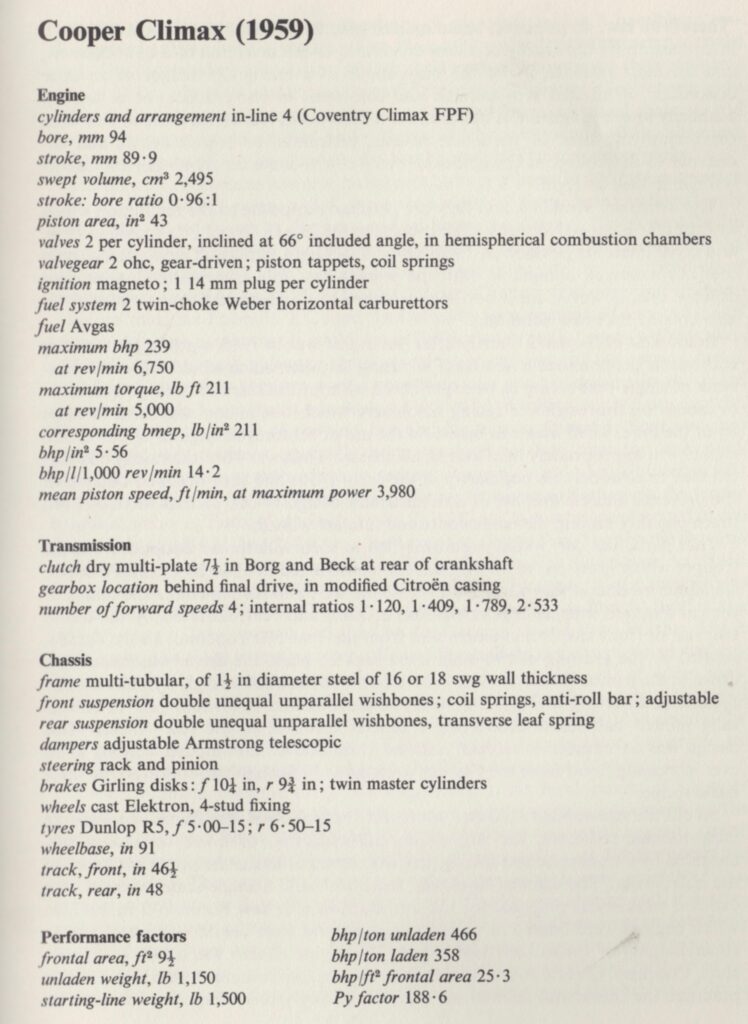

Chassis Type | Prevalence (Decade) | Key Characteristics | Primary Advantage | Key 1950s Example |

Ladder Frame (Body-on-Frame) | Early 1950s (Legacy) | Two longitudinal rails connected by cross-braces. | Simple, robust, low manufacturing complexity. | Early F1, many commercial vehicles |

Tubular Space Frame | Mid-Late 1950s | Multi-tubular, complex triangulation of stress members. | High strength-to-weight ratio, superior torsional rigidity. | Mercedes W196, Cooper T43 |

The Aerodynamic Experiment

The 1954 formula placed minimal restrictions on bodywork, leading Mercedes to consciously experiment with aerodynamics for the W196. The engineers developed two distinct body styles based on anticipated circuit requirements. For ultra-high-speed tracks like Monza and Reims, they introduced the Streamliner (Stromlinienwagen), featuring sleek, torpedo-shaped bodywork with enclosed wheels. This design minimized aerodynamic drag, maximizing straight-line speed, and proved highly successful, with Juan Manuel Fangio winning races and Stirling Moss achieving the fastest lap at the 1955 Italian Grand Prix in this configuration.

For twistier circuits where high-speed drag reduction was less critical than precise handling and driver visibility, Mercedes utilized a conventional open-wheel body. This dual approach demonstrated a pragmatic, advanced understanding that performance optimization required tuning the car’s outer shell based on the circuit’s demands—an early, conscious recognition of aerodynamics as a variable tool, not just an aesthetic feature.

The Braking Imperative: Controlling the Kinetic Energy

As cars like the W196 introduced aerospace-derived chassis rigidity and engine performance increased across the grid, the ability to decelerate reliably became the new competitive bottleneck. By the mid-1950s, traditional braking technology was fatally exposed by the cars’ kinetic energy.

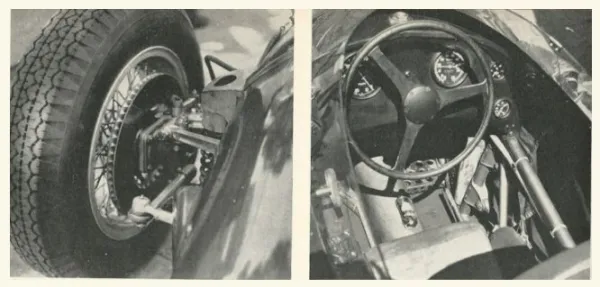

The Flaw of Drum Brakes

Early 1950s Grand Prix cars, including the Mercedes W196 (which initially used giant, centrally arranged Duplex drum brakes), relied on drum brake systems. While drum brakes could generate high initial friction—often enough to lock the narrow tires—they suffered a catastrophic weakness: heat management. Because the pads and friction surfaces are enclosed within the drum, heat is trapped. Under repetitive, hard braking required by faster lap times, this heat would cause the brake pad material to vaporize, creating tiny gas pockets at the contact surface. Worse still, the heat would often cause the brake fluid in the lines to boil, a phenomenon known as vapor lock. Since gas is highly compressible, the hydraulic system would lose pressure, making the brake pedal feel “spongy” and useless, resulting in the dreaded, unpredictable loss of stopping power known as Brake Fade. This thermal limitation forced drivers to adopt highly conservative braking points.

The Le Mans Catalyst and F1 Adoption

The critical solution originated outside of Formula 1, in endurance racing, where the need for consistent performance over 24 hours was paramount. In 1953, Jaguar revolutionized the 24 Hours of Le Mans by winning with the C-Type equipped with innovative disc brakes. Their ability to consistently decelerate faster than rivals, particularly after the high-speed Mulsanne Straight, was the decisive factor, allowing them to achieve an unprecedented average speed of 105 mph.

Despite this clear demonstration of superior consistency and stopping distance—disc brakes offer 17–33% shorter stopping distances compared to drums—F1 teams remained hesitant. There was professional skepticism regarding the disc brake system’s supposed complexity and potential reliability issues compared to the simplicity of the established drums.

The breakthrough into F1 was championed by British manufacturer Vanwall, financed by Tony Vandervell. Having adopted disc brakes since 1954, Vanwall’s engineers dedicated resources to optimizing the technology, even developing their own discs featuring internal radial drilling to improve lightness and heat dissipation. In 1957, Stirling Moss validated this persistence by claiming three World Drivers’ Championship victories in his disc brake-equipped Vanwall, including the landmark win at the British Grand Prix.

The success of the disc brake in F1 was a fundamental paradigm shift. It showed that performance enhancement was not solely about speed, but about deceleration and reliability. The disc brake’s critical advantage lies in superior thermal management; the rotor is fully exposed to outside air, allowing heat generated by friction to dissipate immediately. This prevents brake fade and ensures the driver has consistent stopping power lap after lap—a consistency that instantly became a massive competitive weapon.

Table 2: Drum vs. Disc Brakes in High-Performance 1950s Racing

Feature | Traditional Drum Brakes | Vanwall/Jaguar Disc Brakes | Impact on Racing Dynamics |

Heat Dissipation | Poor (enclosed, prone to fade) | Excellent (exposed rotor and cooling ducts) | Allowed later braking points and consistent performance over a race distance |

Wet Weather Performance | Poor (prone to trapping water) | Good (self-drying due to open design) | Increased driver confidence and reduced variability in performance |

Braking Consistency | Highly variable, prone to vapor lock | Consistent, responsive, less prone to fade | Reliable deceleration became as valuable as acceleration |

The Regulatory Constraints: Fuel, Power, and Nascent Safety (Mid-Decade Shifts)

The mid-1950s saw the FIA introduce regulatory changes aimed at commercial viability, which inadvertently created a technical challenge for engine manufacturers, alongside a stark, slow realization of the dangers inherent in the sport.

The Great Fuel Switch of 1958

Before 1958, F1 engines operated on specialized, high-performance racing fuels, often composed of alcohol blends like methanol or ethanol. Alcohol-based fuels possess characteristics—such as burning cooler—that allow high-compression engines to maximize power output while remaining reliable, yielding impressive horsepower figures from the 2.5L formula.

In 1958, however, the FIA introduced a mandate that engines must run on commercially available petrol, specifically AvGas (aviation standard gasoline with a maximum octane rating of 130). The primary goal of this change was commercial: to allow fuel companies to advertise that races were won using fuels available to the public.

From an engineering perspective, this regulation was a significant handicap. AvGas has a lower energy density and cannot tolerate the extremely high compression ratios achieved with alcohol blends without risking catastrophic pre-ignition (knocking). Consequently, constructors were forced to detune their powerful 2.5L engines, sacrificing peak horsepower to ensure reliability and prevent engine failure. This technical restriction compelled engineers to focus their research away from brute force and toward highly constrained optimization—innovating in combustion chamber design, timing, and mapping to extract maximum possible efficiency and performance from the lower-grade, regulated fuel.

The Fatal Trade-off of Safety

Contrasting sharply with the accelerating technological sophistication of the cars was the shocking indifference toward driver safety throughout the decade. When Formula 1 began, protective gear consisted of rudimentary items: a cloth skull cap (like the one used by Dr. Farina) or a basic leather helmet, cotton overalls, and leather gloves. The structural safety of the cars was equally minimal.

Perhaps the most tragic reflection of the era’s attitude was the controversial consensus regarding seat belts: they were not mandatory and often discouraged. This was based on the dangerously flawed premise that in the event of a high-speed accident and inevitable fire, a driver stood a better chance of survival if they were thrown clear of the vehicle rather than being trapped inside.

Safety improvements were glacially slow. Initial basic engineering changes included introducing the roll bar and using rudimentary fire-resistant materials. However, without mandated six-point harnesses, robust crash structures, and comprehensive medical infrastructure, the human risk associated with high-speed competition remained terrifyingly high. This lack of basic protection serves as a somber footnote to the era, highlighting that while engineers relentlessly pursued speed, the value placed on driver survival was tragically low.

The Copernican Shift: The Mid-Engine Revolution (1957–1959)

The decade’s ultimate and most enduring innovation was the physical repositioning of the engine from the front of the car to the middle (between the axles), a concept that completely redefined race car dynamics and eventually, the design of virtually all high-performance automobiles.

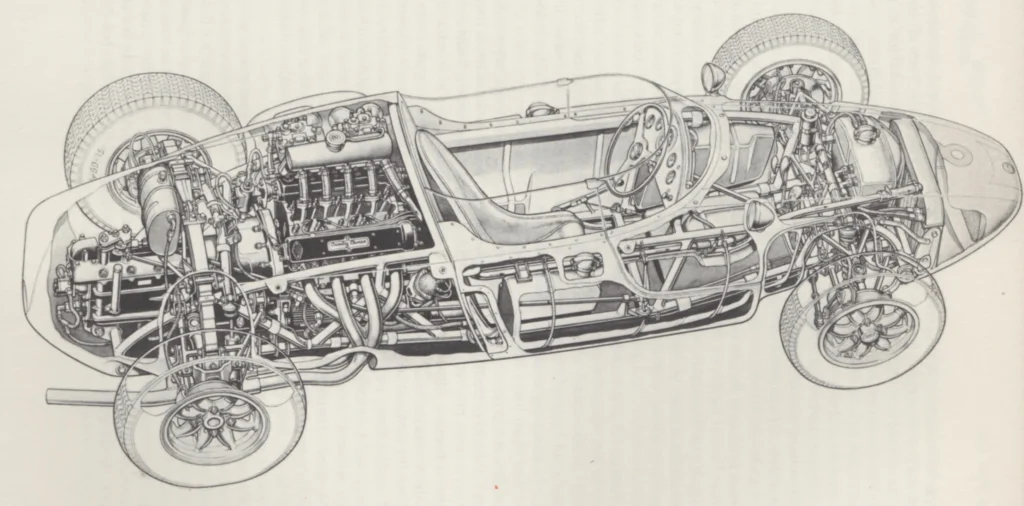

The Origin and the Physics

The conceptual father of the F1 mid-engine car was John Cooper. Working with Eric Brandon in the aftermath of World War II, Cooper began developing lightweight cars for the smaller Formula 3 category. Their philosophy dictated that superior handling and weight distribution could consistently outperform raw, heavy engine power. By placing the engine strategically in the middle of the chassis, Cooper created the seminal prototype for future success.

The technical superiority of this Rear-Mid Engine, Rear-Wheel Drive (RMR) layout is rooted in physics, specifically the concept of the polar moment of inertia. This physics term describes a body’s resistance to rotational acceleration. Traditional front-engined cars placed the heaviest mass (the engine) far forward, creating a large polar moment of inertia, making them inherently resistant to rotation into a corner.

By concentrating the mass near the geometric center of the car (between the axles), the mid-engine layout drastically reduced this polar moment of inertia. This reduced resistance meant the car required significantly less energy to rotate. The dynamic advantage was immense: it allowed drivers to “brake later to the apex and then rotate the car into the turn,” a technique often described as “squaring off the corner,” which could not be executed reliably by heavier, nose-heavy front-engined competitors. Furthermore, placing the engine mass over the rear axle improved rear-wheel traction, aiding both cornering grip and acceleration.

The Triumph of the T43

Despite the success of the mid-engine layout in lower categories like F3 (where drivers like Stirling Moss and Graham Hill gained experience in Cooper cars), established F1 giants like Ferrari and Maserati remained tied to the front-engine formula, skeptical of the radical layout.

The definitive moment arrived at the 1958 Argentine Grand Prix. Stirling Moss, driving the tiny, diminutive Cooper T43 entered by the privateer Rob Walker Racing Team, steered the mid-engined machine to victory. This was a watershed moment in the history of the sport for three key reasons: it was the first World Drivers’ Championship victory for a rear-engined car, the first for a car entered by a privateer team, and the first using an engine supplied by a third party.

The victory proved that superior chassis dynamics and low polar moment of inertia could definitively overcome the horsepower advantages held by the larger, better-funded factory teams. This fundamental shift toward agility and optimized handling established the principle that defines modern motorsport. The revolution was cemented when Jack Brabham won the 1959 World Championship driving the Cooper T51. The success of Cooper—a smaller, agile, engineering-focused “garagiste” team—signaled the inevitable obsolescence of the heavy, front-engined Grand Prix car and heralded the democratization of the sport in the 1960s.

Conclusion: The Foundation of Modern F1

The 1950s, far from being a simple footnote in F1 history, was a chaotic, experimental crucible that birthed the foundational engineering principles of modern Formula 1. The decade witnessed the complete replacement of three core pre-war technologies with three fundamental modern solutions, fundamentally changing race car design:

- Chassis: The heavy, robust Ladder Chassis was supplanted by the sophisticated, high-rigidity Tubular Spaceframe (exemplified by the W196), a structural shift that allowed suspension geometry to function with unprecedented precision.

- Braking: The thermally compromised Drum Brake system was defeated by the consistent, fade-resistant Disc Brake (pioneered by Jaguar at Le Mans and adopted by Vanwall in F1), shifting the performance focus to reliable deceleration.

- Layout: The front-engine design was rendered obsolete by the dynamic superiority of the Mid-Engine Layout (championed by Cooper), proving that handling and superior rotational dynamics were more critical to speed than raw power.

These innovations were driven by necessity, technical constraints (like the 1958 fuel mandate), and the strategic infusion of advanced material science and engineering analysis refined during the war years.

The true legacy of the 1950s lies in its shift in engineering philosophy: F1 moved from valuing simplistic robustness and raw engine output to prioritizing constrained optimization, dynamic agility, and structural rigidity. By the close of the decade, the Cooper T51’s championship victory confirmed the new template, setting the stage for the next generation of engineers, notably Colin Chapman, who debuted Lotus in 1958. Chapman, a brilliant structural engineer, would take the lessons of the mid-engine spaceframe and push them to their logical conclusion with the introduction of the even more rigid monocoque chassis in the early 1960s, a design that remains the structural heart of every Formula 1 car today. The 1950s were thus the decade when Formula 1 transitioned from relying on history to defining the future.

Pingback: Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 Signs Major Partnership with PepsiCo’s Sting Energy | F1 Mavericks