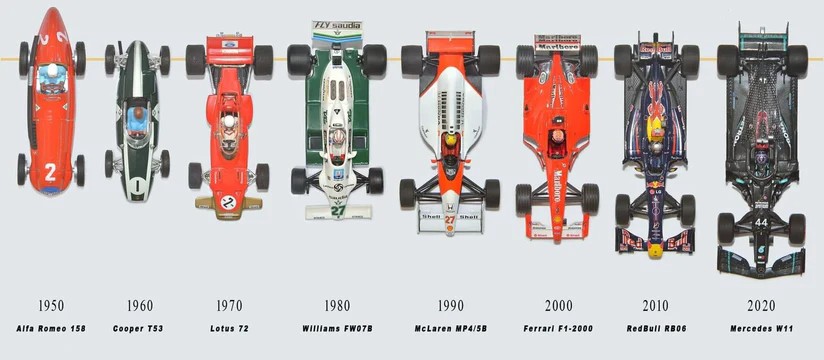

Have you ever wondered how F1 cars evolved from simple racing machines to the highly sophisticated beasts they are today? Formula 1 is a sport that thrives on innovation, and nowhere is this more apparent than in car design. From the early years of rudimentary engineering to today’s cutting-edge aerodynamics and hybrid technology, the transformation of F1 cars has been shaped by technological breakthroughs, safety regulations, and the pursuit of speed. Join us as we uncover the fascinating evolution of Formula 1 car design, revealing how aerodynamics, cutting-edge materials, and powerful engines have shaped these incredible machines.

The Early Years of Formula 1 (1950s – 1960s): Simplicity Meets Speed

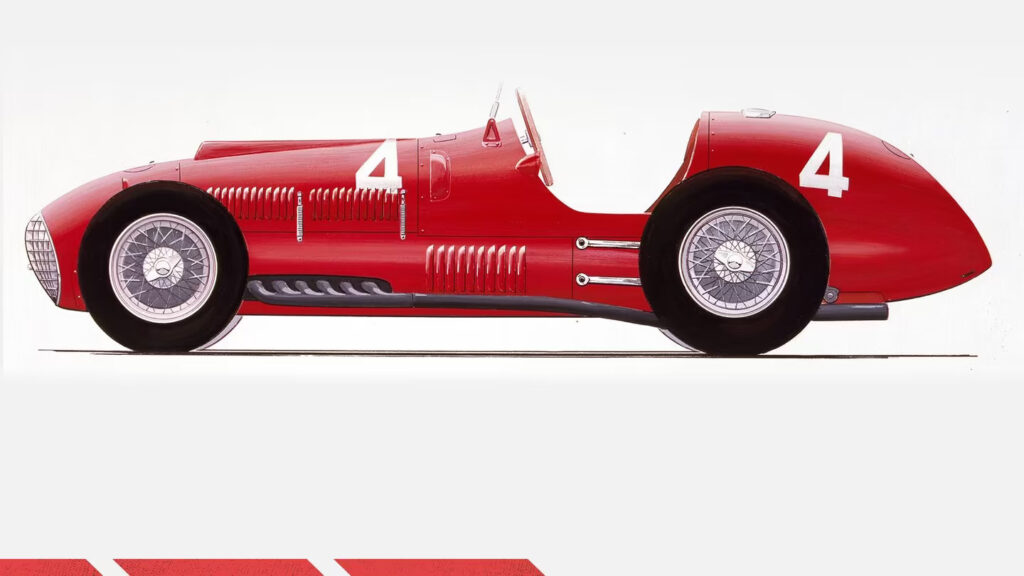

The first Formula 1 cars of the 1950s were a far cry from the highly sophisticated machines we see on the grid today. In the early years of the championship, many cars were little more than modified road vehicles, built with a focus on raw speed rather than advanced engineering. Their designs were simple and straightforward, with front-mounted engines, minimal aerodynamic considerations, and basic steel tube-frame chassis that provided only modest structural rigidity. Safety was almost an afterthought, and drivers had to rely largely on skill and bravery to keep their machines under control.

One of the defining characteristics of early Formula 1 cars was their front-engine layout, a design choice inherited from pre-war Grand Prix cars. While these engines were often large and powerful for their time, their forward placement led to significant handling challenges, especially in high-speed corners. The cars themselves were constructed using a steel tube-frame chassis, a relatively rudimentary design that offered some strength but lacked the rigidity needed for precise handling. Tires were another limiting factor—narrow and lacking modern grip-enhancing compounds, they forced drivers to rely almost entirely on mechanical grip rather than aerodynamic downforce.

At the beginning of the 1950s, aerodynamics played little to no role in F1 car design. Teams were more concerned with making their cars as fast as possible in a straight line rather than optimizing their performance through airflow management. Some early experiments with fins and spoilers emerged toward the end of the decade, but these were mostly intended to reduce lift rather than generate any meaningful downforce. As a result, drivers had to contend with cars that often felt unstable at high speeds, making cornering a true test of skill.

As Formula 1 moved into the 1960s, innovation and experimentation began to reshape the sport. One of the most significant breakthroughs was the shift from front-engine to mid-engine designs. Cooper was the first team to demonstrate the superiority of this layout, and by the mid-1960s, every competitive F1 car had adopted a mid-engine configuration. This revolutionized handling, as moving the engine behind the driver improved weight distribution, making the cars more agile and easier to control through corners. Another key advancement was the introduction of lightweight aluminium body panels, replacing the heavier steel used in previous decades. This had reduced weight, increased performance, and allowed for greater flexibility in car design.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking innovation of the era came in 1962 with the Lotus 25, designed by the legendary Colin Chapman. This car was the first to feature a monocoque chassis, a revolutionary departure from the traditional tube-frame design. By using a stressed-skin structure—similar to those found in aircraft—the monocoque chassis significantly improved structural rigidity while reducing weight. This not only made the car faster but also laid the foundation for modern F1 car construction. The Lotus 25’s success demonstrated the advantages of monocoque design, and soon, every team followed suit.

While the cars of the 1950s and 1960s may seem, primitive compared to today’s cutting-edge machines, this era was crucial in shaping the future of Formula 1. It was a time of raw, unfiltered racing, where driver skill and engineering ingenuity played an equally vital role. Every Grand Prix was an unpredictable battle, fought with machines that demanded absolute commitment from those who dared to push them to the limit. This period set the stage for the technological revolution that would follow, proving that Formula 1 was more than just a sport—it was a laboratory for innovation and progress.

The Rise of Aerodynamics (1970s – 1980s): The Science of Speed

The transition from the relatively simple Formula 1 designs of the 1950s and 60s to the highly complex, aerodynamically advanced machines of the 1970s and 80s marked a turning point in the sport. Engineers began to realize that outright speed wasn’t just about engine power—it was also about how effectively a car could stick to the track through corners. This led to the increasing use of downforce, a vertical force that pushes the car towards the ground, dramatically improving grip and stability. The pursuit of this force would lead to some of the most radical car designs in F1 history.

How Did Aerodynamics Revolutionize F1?

By the early 1970s, teams began incorporating large rear wings, inspired by the aviation industry but inverted to generate downforce rather than lift. Initially mounted high and wide for maximum effect, these wings helped increase cornering speeds by pressing the tires firmly into the asphalt. But engineers quickly realized that front-end aerodynamics were just as crucial. Smaller but increasingly sophisticated front wings emerged, carefully designed to balance the car’s overall aerodynamic profile and prevent instability at high speeds.

However, wings were only the beginning. Teams soon turned their attention to the car’s underbody, recognizing that airflow beneath the car could be manipulated to generate even more downforce. Instead of relying solely on external wings, engineers experimented with sculpted sidepods and venturi tunnels—cleverly shaped channels that accelerated airflow under the car, creating a powerful low-pressure area that effectively sucked the car to the track. This concept, known as ground-effect aerodynamics, would prove to be a game-changer.

The Ground-Effect Revolution

While early attempts at underbody aerodynamics had been made, it was Colin Chapman’s Lotus 79 that truly unlocked the full potential of ground effect in 1978. By using carefully designed skirts along the car’s floor to seal airflow and maximize the low-pressure effect, the Lotus 79 generated enormous levels of downforce without the drag penalty of large wings. The result? Unprecedented cornering speeds and a level of grip that left the competition struggling to keep up.

The dominance of ground-effect cars forced every team to adopt similar designs, and by the early 1980s, the sport had entered an arms race of aerodynamic efficiency. However, with extreme downforce came significant risks. As speeds increased, the forces acting on the cars became dangerously unpredictable, and any disruption in airflow—such as hitting a curb or losing a side skirt—could lead to sudden and catastrophic loss of grip. Concerned for driver safety, the FIA eventually banned full ground-effect designs in 1983, requiring cars to have flat-bottomed floors. This shift didn’t end the pursuit of aerodynamics, but it forced teams to explore new ways to optimize airflow within the rules.

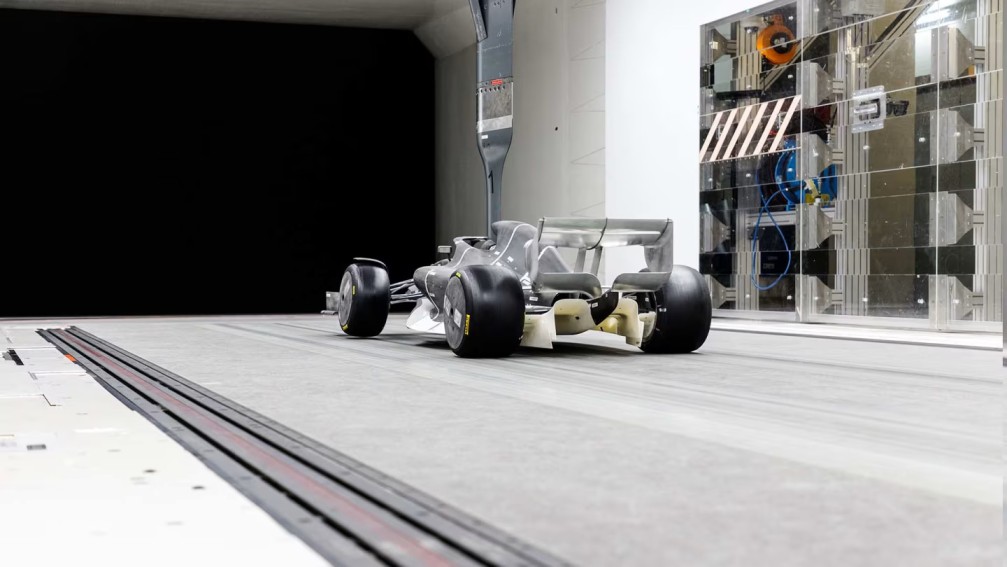

Wind Tunnel Testing Becomes Essential

One of the biggest technical advancements of this era was the extensive use of wind tunnels. Previously, teams relied heavily on trial and error when testing aerodynamic changes, but by the late 1970s, wind tunnel testing had become an essential part of car development. Using scale models, engineers could analyse how airflow interacted with various design elements, fine-tuning everything from wing angles to underbody airflow. This scientific approach to aerodynamics became a cornerstone of F1 development, a trend that continues to this day.

The Pinnacle of 1980s F1 Engineering: The McLaren MP4/4

While many incredible machines emerged during this era, one car stood above the rest: the McLaren MP4/4. Designed primarily by Steve Nichols, though often credited to Gordon Murray, this car dominated the 1988 Formula 1 season like no other before it. It was a masterpiece of aerodynamics, blending sleek bodywork with an ultra-efficient underbody design and meticulously optimized wings.

The MP4/4 was powered by the Honda RA168E, a formidable turbocharged V6 engine that delivered immense power while maintaining exceptional fuel efficiency—a crucial factor in an era of strict fuel regulations. Combined with an advanced carbon fibre monocoque chassis, the car was incredibly lightweight yet structurally strong, allowing it to extract maximum performance from its aerodynamics.

With Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost behind the wheel, the MP4/4 won 15 out of 16 races in 1988, an almost unimaginable level of dominance. Its success was not just about raw speed; it was a testament to how aerodynamics had evolved into one of the most critical aspects of Formula 1 design.

Why This Era Mattered

The 1970s and 80s were the decades in which Formula 1 fully embraced aerodynamics as a science. What started as simple bolt-on wings had evolved into a deeply complex discipline, shaping every inch of an F1 car’s design. The pursuit of downforce led to groundbreaking innovations, and even though extreme ground-effect cars were eventually outlawed, their influence never disappeared.

Today’s Formula 1 cars, with their sophisticated underfloor designs and advanced computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, owe much of their DNA to this revolutionary period. The question remains—what’s the next great aerodynamic breakthrough waiting to be discovered?

The Turbo Era & Advanced Materials (1980s – 1990s): Power, Speed, and Innovation

The 1980s and early 1990s were one of the most thrilling yet chaotic periods in Formula 1 history. It was a time of raw power, rapid technological evolution, and groundbreaking materials, all of which transformed the sport forever. The emergence of turbocharged engines redefined performance, pushing cars to previously unimaginable speed levels. In qualifying trim, these monstrous machines often produced over 1,000 horsepower, with some reports suggesting peak figures close to 1,400 hp—power outputs that remain unmatched in Formula 1 history. However, with such mind-blowing power came immense challenges, leading to some of the most spectacular racing—and technical failures—ever seen in the sport.

Turbocharged Power: The Fastest F1 Cars Ever?

Turbocharging itself was not new to motorsport, but Formula 1 engineers in the 1980s took it to an extreme. These engines used exhaust gases to spin a turbine, which compressed incoming air, increasing power dramatically. Teams like Renault, BMW, Ferrari, Honda, and Porsche (with TAG) pushed the limits of what was mechanically possible. In the height of the qualifying wars, teams turned up the boost pressure to such extreme levels that engines were built to last just a handful of laps before self-destructing.

However, turbocharging came with a significant downside—turbo lag. Because turbochargers needed time to spool up, there was a noticeable delay between pressing the throttle and the engine delivering full power. This made handling incredibly tricky, especially mid-corner, where drivers needed precise control. One moment, they had nothing, and the next, they were wrestling with an explosive burst of power, often sending them spinning off the track. Managing this power required immense skill and bravery, making this era one of the purest tests of driver ability in F1 history.

The Rise of Carbon Fiber and Cutting-Edge Technology

While turbocharged engines dominated headlines, other revolutionary advancements were also shaping the sport. One of the most significant breakthroughs was the introduction of carbon fibre composite chassis, pioneered by McLaren with the MP4/1 in 1981. Before this, cars were built from aluminium or steel, which were heavier and structurally less efficient. Carbon fibre offered a vastly superior strength-to-weight ratio, making cars not only lighter and faster but also much safer. Today, carbon fibre remains the gold standard in Formula 1 construction.

Another game-changing innovation was the introduction of semi-automatic gearboxes. Traditionally, drivers had to take their hands off the wheel to shift gears using a manual stick. However, in the late 1980s, teams like Ferrari experimented with paddle-shift systems that allowed seamless gear changes without lifting off the throttle. This not only improved lap times but also made gear shifts far more reliable under extreme racing conditions. By the early 1990s, semi-automatic transmissions had become standard in Formula 1, paving the way for the highly advanced electronic systems we see today.

The Dark Side of Turbo Power: Unreliability & Safety Concerns

Despite their insane performance, turbo engines had serious drawbacks. The immense power output put extreme stress on the engines, leading to frequent and dramatic failures. Blown turbos, overheating issues, and exploding pistons were common sights in races. The intense heat generated by turbocharging also posed significant fire risks, with many cars catching fire mid-race. The infamous reliability issues meant that while turbo cars could deliver lightning-fast lap times, finishing a race without mechanical failure was often a challenge.

As the speeds increased, so did the dangers for drivers. The combination of unpredictable turbo lag, excessive power, and fragile engines contributed to several high-profile accidents. Concerned about safety, the FIA stepped in, implementing progressive restrictions on boost pressure and fuel consumption in an attempt to curb excessive power. By 1989, turbocharged engines were officially banned, forcing teams to return to naturally aspirated engines. However, the knowledge gained from the turbo era would heavily influence future engine development.

Key Cars: Engineering Masterpieces of the Era

While turbo engines defined the 1980s, the technological advancements of the era extended beyond just power. Some of the most innovative cars in Formula 1 history emerged during this period, showcasing how teams sought to combine raw speed with cutting-edge engineering.

One of the most advanced cars of the early 1990s was the Williams FW14B, driven by Nigel Mansell. This car wasn’t defined by turbocharging but by its revolutionary active suspension system. Unlike traditional suspensions that relied on mechanical components, active suspension used electronic sensors and hydraulics to continuously adjust ride height and stiffness in real-time, optimizing grip and stability. This gave the FW14B a massive advantage, making it one of the most dominant cars ever seen in Formula 1.

Ferrari, despite struggling for championship success in this era, was another pioneer of technological innovation. The Ferrari F1-90 was among the first F1 cars to experiment with electronic driver aids, including early versions of traction control and automatic shifting systems. These electronic advancements were designed to help manage the immense power of turbo engines and foreshadowed the high-tech driver-assist systems that would become common in later decades.

Legacy: What Did This Era Teach Formula 1?

The Turbo Era of the 1980s remains one of the most extreme and exhilarating periods in F1 history. It was an era of unbridled power, fearless drivers, and relentless engineering innovation. However, it also highlighted the need for better control over performance, improved safety measures, and smarter use of materials.

Many of the advancements from this period—carbon fiber chassis, semi-automatic gearboxes, electronic driver aids, and advanced aerodynamic principles—became essential elements of modern Formula 1. The return to naturally aspirated engines in the 1990s allowed engineers to shift their focus towards efficiency, handling, and reliability, setting the stage for the next generation of F1 innovation.

The lessons learned during the turbo era continue to influence the sport today, as Formula 1 enters a new age of hybrid power units and advanced energy recovery systems. While the sheer spectacle of 1,400-horsepower monsters may never return, the relentless pursuit of performance and technological breakthroughs that defined the 1980s lives on.

The Modern Era: Aerodynamic Revolution (2000s – 2010s)

The 2000s and 2010s in Formula 1 marked a dramatic shift in how performance was extracted from a car. While aerodynamics had played a crucial role since the 1970s, this era saw teams pushing the limits of airflow management like never before. Engineers fine-tuned every inch of the car’s bodywork, designing intricate aerodynamic components that maximized downforce (to increase cornering speeds) while minimizing drag (to maintain high straight-line speeds). This relentless pursuit of aerodynamic perfection eventually became the single biggest differentiator between the fastest and slowest teams, overshadowing even engine performance in many cases.

The Shift in Engine Philosophy: A Return to Naturally Aspirated Power

Following the turbocharged monsters of the 1980s, Formula 1 entered the 2000s with naturally aspirated engines that, while slightly less extreme in raw power, were far more predictable and reliable. The early 2000s were dominated by 3.0-liter V10 engines, producing around 900 horsepower, delivering high-revving, ear-splitting performance that defined an era. However, in 2006, the FIA mandated a switch to 2.4-liter V8 engines, which, while still powerful, were slightly more restricted to curb rising costs and improve reliability.

Yet, despite this shift, engines were no longer the primary factor in lap time improvements. Teams began realizing that the key to performance gains lay in aerodynamics—how efficiently the car could manipulate air to create downforce without excessive drag.

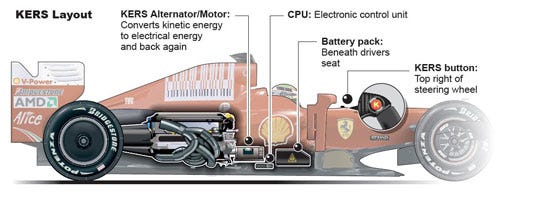

The Rise of Energy Recovery: KERS & Hybrid Beginnings

As part of Formula 1’s push towards innovation and sustainability, Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems (KERS) were introduced in 2009, offering a glimpse into the hybrid technology that would later dominate the sport. KERS allowed teams to recover kinetic energy under braking, store it as electrical energy, and then deploy it in short bursts to improve acceleration or aid in overtaking. While initially heavy and unreliable, KERS provided an extra 80 horsepower for about 6.6 seconds per lap—a crucial advantage in wheel-to-wheel racing.

Although not universally adopted at first, KERS became a stepping stone for the hybrid era, which arrived in 2014 with the introduction of the turbocharged V6 hybrid engines. But before that seismic shift, teams spent the 2000s and early 2010s obsessing over aerodynamic innovations that would define the era.

The Aerodynamic Arms Race: Sculpting the Fastest Cars in History

This period saw the most complex and intricate aerodynamic components ever designed in Formula 1. The front wing, once a relatively simple structure, morphed into an ultra-detailed multi-element masterpiece, featuring winglets, flaps, and endplates carefully designed to guide airflow around the car.

Bargeboards, once minor features, became massive sculpted aerodynamic devices, directing airflow along the sides of the car to reduce turbulence and improve overall aerodynamic efficiency. Meanwhile, rear diffusers became crucial performance differentiators, carefully engineered to control how air exited the car, generating additional downforce without the drag penalty of a large wing.

Pushing the Limits: The Controversial Innovations

As teams chased every millisecond, they often exploited loopholes in the regulations to gain an advantage. Some of the most controversial yet brilliant aerodynamic innovations of the era included:

- Blown Diffusers (2010-2011) – Teams discovered that by directing hot exhaust gases towards the diffuser, they could generate extra downforce, even when the driver was off-throttle. This meant cars stuck to the track better in corners, allowing for higher speeds. However, the FIA saw this as an artificial aerodynamic aid and eventually banned it.

- Double Diffusers (2009-2010) – Initially exploited by Brawn GP, Toyota, and Williams, this design cleverly split the diffuser into two levels, increasing downforce dramatically. The result? Brawn GP dominated the 2009 season, winning both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships, forcing the FIA to ban the concept in 2011.

- F-Duct (2010) – Developed by McLaren, the F-Duct was a driver-activated system that disrupted airflow over the rear wing to reduce drag on straights, increasing top speed without compromising cornering ability. Soon copied by rivals, this system was outlawed by the FIA in 2011.

While these innovations were brilliant examples of engineering ingenuity, they often led to fragile and over-complicated car designs. Even minor damage to a winglet or a bargeboard could dramatically impact a car’s performance, making them incredibly sensitive to racing conditions.

The Most Iconic Car of the Era: The Ferrari F2004

Among the many legendary cars of the modern aerodynamic era, one stands above the rest—the Ferrari F2004. Driven by Michael Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello, the F2004 dominated the 2004 season, winning 15 out of 18 races and securing Schumacher’s seventh and final World Championship.

Designed by Rory Byrne and Ross Brawn, the F2004 perfectly balanced power, aerodynamics, and reliability. While its V10 engine was immensely powerful, it was the car’s flawless aerodynamic efficiency that made it untouchable. The F2004’s sleek bodywork, low-drag design, and advanced front and rear wings made it one of the fastest Formula 1 cars ever built. Many of the lap records set by this car stood for over a decade, only broken by the hybrid-era cars of the late 2010s.

A New Era on the Horizon

The 2000s and 2010s were the golden age of aerodynamics, but as the technology became increasingly complex, the FIA realized that the extreme reliance on aero had made overtaking more difficult. Cars became so aerodynamically sensitive that following another car closely disrupted airflow, making it almost impossible to pass without a significant pace advantage.

By the end of the 2010s, Formula 1 faced a crossroads: Should it continue the ultra-aero approach, or shift toward regulations that promote closer racing? This question would define the next phase of the sport, leading to the 2022 regulation changes designed to simplify aerodynamics and improve wheel-to-wheel competition.

Do you think Formula 1 should continue its aerodynamic revolution, or should the sport focus on improving close racing? Let us know your thoughts below!

The Current Era (2020s – Present): Regulation-Driven Changes

The current era of Formula 1, which began in the 2020s, represents a major turning point in the sport’s history. It marks a significant shift in design philosophy, driven by a new set of regulations aimed at improving racing dynamics. In response to feedback from drivers, teams, and fans, Formula 1 recognized that the highly complex and intricate aerodynamic designs of the previous decade had made overtaking increasingly difficult and led to large performance gaps between the teams. This prompted the FIA to implement sweeping changes, transforming the way F1 cars were built and raced.

A Return to Ground-Effect Aerodynamics

One of the most significant changes in the 2022 regulations is the return of ground-effect aerodynamics, which now serve as the primary means of generating downforce. Ground effect, first introduced in the 1970s and fully realized in the 1980s, works by shaping the car’s underbody to create a low-pressure area beneath the car, effectively “sucking” the car down onto the track and improving cornering performance.

However, the current implementation of ground effect is notably more regulated and prescriptive than in the 1980s. The FIA has carefully designed these regulations to limit the creation of “dirty air”—the turbulent, swirling air that disrupts the aerodynamics of following cars, making overtaking almost impossible. As a result, front wings are now simpler with fewer complex elements, and the underbody shapes are standardized, allowing for more consistent and cleaner airflow for the following cars. The rear wings have also been reworked to ensure that they generate downforce without exacerbating the dirty air problem.

This streamlined approach to aerodynamics has created the possibility for more competitive, close-quarters racing, where cars can follow each other more closely without losing downforce, making it easier to execute overtaking manoeuvres.

Cost Cap and Financial Fair Play

Another game-changing introduction is the cost cap, which limits the amount of money each team can spend on car development during the season. This has been one of the most controversial yet transformative measures, aimed at reducing the vast spending disparities between the wealthiest and least funded teams. Prior to the cost cap, top teams like Mercedes, Red Bull, and Ferrari had a massive financial advantage, allowing them to pour endless resources into car development, resulting in performance gaps that made it difficult for smaller teams to compete.

With the cost cap in place, teams are now forced to be more strategic and efficient in their design choices, finding innovative solutions without exceeding their budgets. This not only improves financial fairness in the sport but also encourages smarter engineering and development across the board.

Hybrid Technology and Sustainable Fuel

As sustainability becomes a growing priority for the automotive industry, Formula 1’s future will be shaped by hybrid power units and sustainable fuel technologies. While hybrid powertrains have already been in use since 2014, the current era sees an even greater focus on efficiency and reducing emissions. The energy recovery systems (ERS) that convert kinetic energy into electrical energy are now a vital part of every car’s performance, providing an additional boost during acceleration and helping teams balance power with fuel efficiency.

Moreover, sustainable fuels have become a major focus for the sport’s long-term vision, with Formula 1 aiming to transition to fully sustainable fuels in the near future. This aligns with the sport’s goal to reduce its carbon footprint while maintaining the thrilling performance that fans have come to expect.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in Formula 1 is another exciting development for the sport. As teams continue to push the boundaries of performance optimization, AI and machine learning are increasingly being used for advanced simulation and data analysis. Teams can now simulate entire race weekends and model performance across different tracks, conditions, and strategies in real time. This allows engineers to make smarter decisions on car setup, tire management, and race strategy, taking much of the guesswork out of the equation. In some cases, AI-driven systems may even help adjust car settings during a race based on the evolving conditions and real-time data.

Notable Cars of the Era: Red Bull RB19 and Mercedes W13

The Red Bull RB19 from the 2023 season is perhaps the best example of the new-generation car under the 2022 regulations. Designed around the ground-effect principles, the RB19 maximized aerodynamic efficiency, giving Red Bull a significant edge in both qualifying and race pace. The car’s ability to maintain downforce even when closely following another car proved its superiority in terms of both raw performance and race craft. Red Bull’s dominance in 2023 showcased the potential of these new regulations to bring closer, more exciting racing.

In contrast, Mercedes’ W13 highlights the challenges of adapting to the new rules. Despite being a powerhouse in the previous decade, Mercedes struggled with “proposing”—a bouncing phenomenon caused by the car’s underbody interacting with the track surface. This issue affected the team’s performance early in the 2022 season and showed just how delicate the balance of aerodynamics and suspension systems is under the new regulations. Mercedes’ struggles with the W13 also underscored the complexity of understanding the intricate interplay between aerodynamics, suspension, and tire behaviour in these cars.

The Road Ahead: Formula 1's Vision for the Future

The future of Formula 1 looks towards even greater sustainability, with an increased reliance on hybrid technology and green fuels. But it’s not just about the engines—the sport is also focusing on making the racing more exciting. Future regulations will likely continue to emphasize the development of cars that allow for closer racing, further reducing the aerodynamic problems of following another car. With AI and data-driven approaches continuing to evolve, expect even smarter engineering and strategic innovations that will drive the sport into a new era of thrilling competition.

What do you think of the new era of F1? Will the changes bring the close racing fans have been asking for, or are the challenges of balancing innovation with regulations too much? Let us know your thoughts below!

At last it a journey which started from their humble beginnings as modified road cars to the cutting-edge, technologically advanced machines we see today, Formula 1 car design has undergone a dramatic transformation. This evolution has been driven by a relentless pursuit of speed and performance, with aerodynamics, materials science, and engine technology all playing crucial roles. We’ve seen the rise and fall of turbochargers, the revolutionary impact of ground-effect aerodynamics, and the increasing importance of sustainability and cost control in the modern era. As Formula 1 continues to push the boundaries of innovation, the future of car design remains an open question. Whether it involves sustainable fuels, further refinements in aerodynamics, the integration of artificial intelligence, or perhaps even a shift to alternative power sources like electric or hydrogen engines, one thing is certain: the evolution of Formula 1 car design is a continuous process, and the quest for the ultimate racing machine will never cease.

I enjoy what you guyhs are up too. This kind of clever work and exposure!

Keeep up the superb works guys I’ve included you guys to my blogroll. http://boyarka-inform.com/

Pingback: Classic F1 Glory: The Untamed Era of Vintage Racing - Not Just a Car

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is a really well written article.

I will be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post.

I’ll definitely comeback.

Greetings from Idaho! I’m bored to death at work so I decided to

browse your blog on my iphone during lunch break.

I enjoy the information you present here and can’t wait to take a

look when I get home. I’m amazed at how fast your blog loaded on my phone ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, very good blog!

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this

board and I find It really useful & it helped me

out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others

like you helped me.

I’d like to find out more? I’d want to find out some additional

information.

No matter if some one searches for his essential thing, thus he/she desires to be available that

in detail, so that thing is maintained over here.

It’s nearly impossible to find experienced people about this topic, but you seem like

you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Superb article! Is it possible to have a Q&A ;on going section mostly answered by someone who knows the answers absolutely? So, for instance are there older models that outperformed the newer models? When chassis changed was there years when old and new raced officially? Was there a time when the official rules organization insisted the same rules for the number of cylinders height, weight, types and numbers of tire changes? And like certain stock car race categories F1 considered “ anything is allowed “ ( Thinking of the STP PAXTON TURBO CAR of Indianapolis 500 races in the mid 1960’s. I vaguely recall a car that didn’t need gasoline to run which was also outlawed. If I’m not mistaking in stock car racing the unlimited class was call F X for factory experimental

Thoughts? Feedback?

Superb article! Is it possible to have a Q&A ;on going section mostly answered by someone who knows the answers absolutely? So, for instance are there older models that outperformed the newer models? When chassis changed was there years when old and new raced officially? Was there a time when the official rules organization insisted the same rules for the number of cylinders height, weight, types and numbers of tire changes? And like certain stock car race categories F1 considered “ anything is allowed “ ( Thinking of the STP PAXTON TURBO CAR of Indianapolis 500 races in the mid 1960’s. I vaguely recall a car that didn’t need gasoline to run which was also outlawed. If I’m not mistaking in stock car racing the unlimited class was call F X for factory experimental

Thoughts? Feedback?

Has F1 ever employed 4 wheel steering?