The Sepang International Circuit (SIC) was never merely a ribbon of asphalt in the jungle; it was a physical manifestation of a nation’s ambition and a punishing crucible for the world’s elite racing drivers. From its inauguration in 1999 until its emotional swansong in 2017, the Malaysian Grand Prix defined itself through two inescapable characteristics: volatility and virulence. The track experience was dominated by the oppressive equatorial climate—a furnace-like combination of blistering heat and humidity that taxed human and machine to their absolute limits.

This relentless atmosphere ensured that the Malaysian Grand Prix was fundamentally a test of physical endurance and strategic acumen, far surpassing the demands of many traditional circuits. The defining feature of the Sepang experience was the ever-present, unpredictable threat of the tropical monsoon. A clear, furnace-hot day could transition within minutes into a torrential downpour, creating conditions so treacherous and visibility so low that strategy often dissolved into chaos. This volatile climate was, in effect, a crucial element of the track design, ensuring that success at Sepang required not just speed, but unparalleled adaptability.

The circuit’s demanding nature meant that it reliably elevated the most exceptional talents in the sport. A review of the winners’ roster confirms this unique standard, showing that the sport’s greatest drivers thrived on its challenging, exhilarating stage. Champions such as Sebastian Vettel claimed four victories, while Michael Schumacher and Fernando Alonso each earned three wins during their dominant eras. The specific list of multi-time winners solidifies Sepang’s reputation as a true measure of skill, reinforcing the deeply felt nostalgia among experts who believe Formula 1 lost one of its few genuinely challenging modern venues when the race departed the calendar. The story of Sepang, therefore, is not just a history of a racetrack, but a narrative of geopolitical symbolism, architectural achievement, and, ultimately, the triumph of economics over sporting merit.

The high-stakes nature of Sepang was further magnified when the Grand Prix moved from the end of the season to the beginning of the calendar starting in 2001. Placing the race so early meant teams were still adapting to new equipment and new regulatory interpretations. Coupled with the volatile climate, this calendar placement consistently produced topsy-turvy results and amplified the drama associated with the scramble for position into the track’s tight first corner complex. Sepang rarely hosted a dull race, serving instead as a severe and complex examination right at the start of every championship campaign.

The National Project: Forging a Modern Icon (1997–1999)

The genesis of the Sepang International Circuit was rooted in a sweeping national vision. Its construction was not merely a commercial endeavor but a flagship component of Malaysia’s aggressive modernization drive, championed by then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad. The government initiated a series of major infrastructure projects throughout the 1990s, and the Sepang circuit was conceived as a highly visible, state-of-the-art facility intended to project Malaysia’s technological and administrative competence onto the global stage through the powerful lens of Formula 1.

Geographical placement confirmed the circuit’s political symbolism. Sepang was built close to Putrajaya, the newly established administrative capital of Malaysia. This proximity underscored the deliberate intention that the circuit should be viewed as an extension of the nation’s new, progressive governance structure, showcasing global capability to the world.

The Architect and the Engineering Marvel

For the design commission, the Malaysian government turned to German engineer Hermann Tilke. The selection was profoundly significant, as Sepang became the very first Formula 1 circuit designed by Tilke to be included on the F1 calendar. The project spanned an intense period from 1997 to 1999. Work officially began in December 1996, and the entire construction required just 14 months to complete, an extraordinary timeline that often necessitated over 1,000 workers on site simultaneously. The total construction cost was RM286 million (approximately 12 million USD at the time).

One of the most defining aspects of the construction was the immense geotechnical challenge presented by the chosen site. The area was composed of highly compressible soil, characteristic of swamps and marshes located near watercourses. Building a complex, high-speed circuit intended to host the highest level of motorsport on such ground required substantial consolidation work to prevent the shear failure of the fill used to establish the structure.

Engineers utilized advanced techniques, including vertical drains, to hasten the drainage of water expelled from the foundation when subjected to external pressure. These measures were critical not only for stabilizing the swampy land and ensuring stability against slides but also for shortening the time of settlement, thus preventing excessive and uneven settlement after the pavement was in place. This costly and time-consuming engineering endeavor underlines the immense political commitment and national resources invested. The circuit was not merely built, it was wrested from the marsh, a third-order display of technological and financial ambition that set the stage for its subsequent, dramatic 19-year run. The facility was officially completed in November 1998 and inaugurated by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in March 1999.

Tilke’s Finest: A Technical and Aesthetic Analysis

Sepang holds a unique and revered status among motorsport aficionados and industry professionals alike. While Hermann Tilke’s later designs often drew criticism for lacking “soul” or following a predictable “template,” Sepang is consistently cited as his finest work. This distinction rests on the track’s flowing geometry, its deliberate promotion of overtaking, and its distinctive aesthetic features.

The Flowing Layout and Overtaking Philosophy

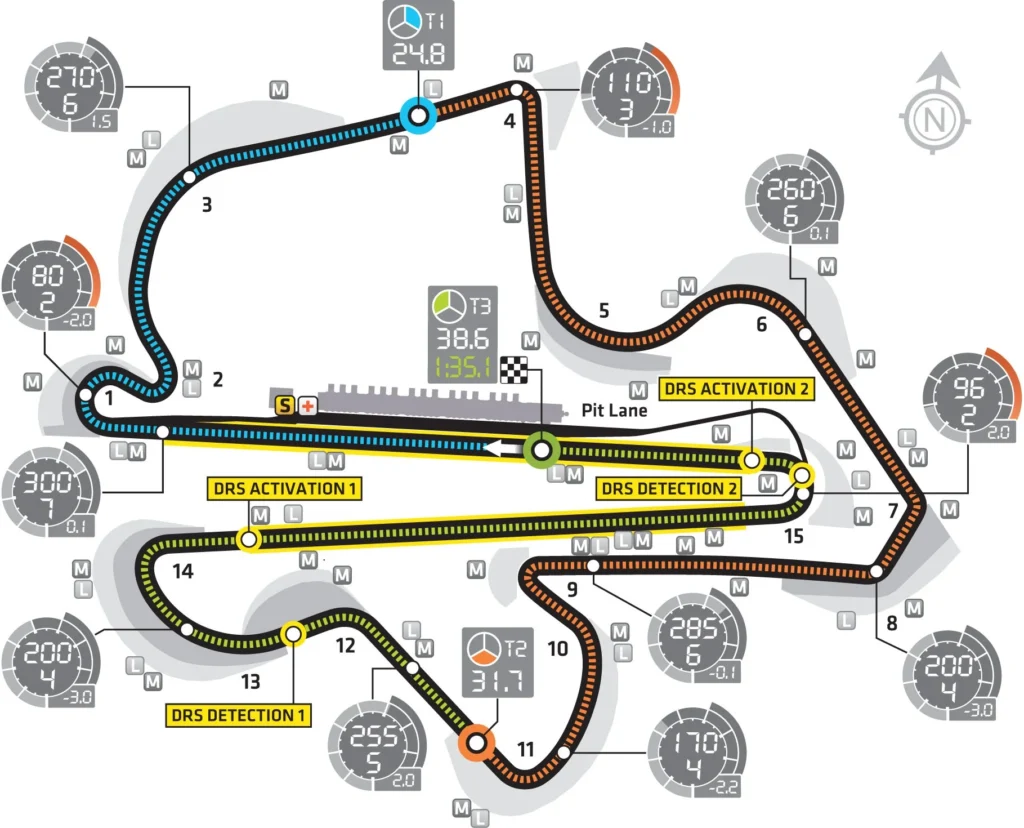

The Sepang circuit stretches 5.543 km (3.444 miles) and incorporates 15 challenging corners and eight straights. Unlike some narrower modern tracks, Sepang was built to be exceptionally wide, ranging from a minimum of 16 meters to 20 meters in certain areas. This generous width was crucial, as it allowed drivers to choose multiple racing lines through corners and offered excellent opportunities for side-by-side running, fundamentally promoting exciting on-track action.

The track was strategically designed to maximize overtaking in an era preceding the introduction of the Drag Reduction System (DRS). The layout features two extensive straights separated by a sharp, technical section. The most critical overtaking zone was the Turn 15 hairpin, which leads directly onto the main straight. Furthermore, Turns 1, 4, and 9 were also known to facilitate genuine side-by-side challenges, demonstrating a commitment to racing excitement that defined the track’s identity.

Architectural Feature | Specification/Description | Strategic Impact/Source |

Designer | Hermann Tilke | First F1 design, considered his ‘finest’ work |

Inauguration/Cost | 1999 (Construction: 1997–1999). Cost: RM286 million | Symbol of Malaysia’s geopolitical modernization push |

Length (Full Circuit) | 5.543 km (3.444miles); 15 corners, 8 straights | Meets FIA Grade 1 standard |

Track Dimensions | Minimum 16m, rising to 20m in certain areas | Contributes to flowing design and excellent side-by-side racing lines |

Key Overtaking Zones | Turns 1, 4, 9, and Turn 15 (Hairpin) | Enabled pre-DRS overtaking and high strategic complexity |

Collaboration and the ‘Soul’ of Sepang

The quality of Sepang’s layout has led to suggestions that it benefited from specialized consultation not typically available for later, mass-produced Tilke designs. It is widely circulated, though difficult to verify, that legendary driver Michael Schumacher was partially involved in consulting on the circuit’s design.

While the extent of his involvement remains debated, the theory holds credence: collaboration with top drivers was instrumental in creating the challenging “soul” possessed by historic venues like Interlagos (re-designed with Ayrton Senna’s input) or Mosport (consulted upon by Stirling Moss). If Sepang did benefit from such input, it would explain why it stood apart from the more sterile, template-driven circuits that followed. The design appeared dedicated to pushing the technical and physical limits of F1 machinery, rather than simply meeting minimum safety specifications, establishing a sophisticated benchmark for the new wave of F1 circuits.

Aesthetically, the circuit was also immediately recognizable. Its capacity for approximately 130,000 spectators was anchored by the unique double-fronted main grandstand. This distinctive structure featured the famous ‘umbrella shade’ design, intended to provide spectators with much-needed protection from the intense sun and sudden monsoon rains.

The Sepang Saga: Defining Moments of Chaos and Strategy (1999–2017)

The Sepang International Circuit immediately earned its reputation as a theatre of high drama, controversy, and brilliance. Its 19-year tenure on the F1 calendar produced some of the most memorable races of the modern era, frequently leveraging its unpredictable climate to create strategic chaos.

The Controversial Debut (1999)

The inaugural Malaysian Grand Prix instantly plunged the venue into global controversy, showcasing its ability to host political and legal drama alongside high-speed action. The race marked the highly anticipated return of Michael Schumacher following a broken leg sustained earlier that year. Schumacher dominated the proceedings, but in a masterful display of team strategy, he famously slowed to hand the victory to his teammate, Eddie Irvine, who was still locked in a fierce battle for the Drivers’ Championship.

However, the drama intensified post-race when both Ferraris were initially disqualified due to a technical irregularity concerning their bargeboards. The subsequent legal appeal and reinstatement of the results only a few weeks later ensured that Sepang’s debut race was defined by bureaucracy as much as blistering speed, setting a chaotic precedent for the years to come.

Monsoon Masterclass (2001)

The shift of the Grand Prix to the early part of the calendar in 2001 amplified the volatility of the weather. That year’s event was hit by a heavy, sudden rainstorm mid-race, transforming the track into a near-uncontrollable water chute.

The conditions led to immediate chaos. Both Michael Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello spun off almost simultaneously at the same corner. Remarkably, the two Ferraris recovered, executing a rapid, coordinated pit stop for wet tires before the field fully recognized the severity of the storm. This brilliant strategic maneuver and Schumacher’s driving mastery in the atrocious conditions allowed them to carve through the field. For a long period, they were nearly five seconds faster than anyone else on track, ultimately securing an astonishing Ferrari 1–2 finish. This strategic triumph is often hailed as one of Michael Schumacher’s greatest drives and a tactical masterstroke by Ferrari, demonstrating that Sepang rewarded adaptability above all else.

The Sunset Disaster (2009)

The 2009 race marked a critical failure stemming from commercial strategy attempting to override environmental reality. Following the runaway success of the Singapore Grand Prix—Formula 1’s first night race—Sepang’s management attempted to capture some of the spectacle by aiming to become the second night race. While this ambition was ultimately scaled back, they settled for a risky late-afternoon start time of 17:00 local time.

The decision proved disastrous. As the race progressed, heavy rainfall arrived around sunset. The low light filtering through the dense clouds, combined with the spray, rendered visibility extremely unsafe for the drivers. The race was red-flagged and ultimately never restarted. Because the race ended prematurely on Lap 33, falling short of the required 42 laps for full distance, the consequences were significant: both driver and constructor results were halved in relation to points. This publicly visible failure was a direct result of commercial pressures—the need to compete with Singapore’s novelty factor—which resulted in a scheduling choice that ignored the highly volatile tropical climate.

The Underdog Triumph (2012)

Sepang continued to provide shock results right up to its final years. The 2012 Grand Prix, also severely impacted by rain, is remembered for its underdog triumph. Fernando Alonso, driving a struggling Ferrari, claimed an unexpected victory in chaotic, drying conditions.

The critical moment came during a high-stakes duel with Sergio Pérez, who drove for the Ferrari-powered Sauber team. Pérez drove an exceptional race and pressured Alonso heavily in the late stages before a minor mistake cost him the lead. Alonso’s win was a triumph of driver skill and strategic opportunism, underscoring Sepang’s ability to level the competitive playing field, allowing exceptional talent to shine even when their machinery was not strictly dominant.

The consistency with which the sport’s greatest names capitalized on Sepang’s unique demands cemented its place in motorsport lore:

Legacy of Greatness: Multi-Time Sepang Winners (1999–2017)

Driver | Total Wins at Sepang | Years of Victory |

Sebastian Vettel | 4 | 2010, 2011, 2013, 2015 |

Michael Schumacher | 3 | 2000, 2001, 2004 |

Fernando Alonso | 3 | 2005, 2007, 2012 |

Kimi Räikkönen | 2 | 2003, 2008 |

The Erosion of Appeal and the Economic Squeeze

Despite its illustrious racing history and architectural quality, the Malaysian Grand Prix faced a steady erosion of commercial and governmental support in the 2010s, culminating in its exit from the F1 calendar after the 2017 race. The demise was a consequence of economic reality colliding with the high-cost demands of modern Formula 1 hosting.

Infrastructure Stagnation and External Criticism

Signs of decline were evident long before the final decision. As early as 2007, F1 President Bernie Ecclestone publicly voiced concerns. While he acknowledged that the circuit itself was sound, he noted that the surrounding infrastructure and environment were getting “shabby” and “a bit tired” from a perceived lack of care. This critique pointed toward a long-term failure to maintain the high level of external investment necessary to sustain the prestige the circuit held at its 1999 inauguration. The political will and funding that had forged the icon from swamp land appeared to be diminishing.

The Cost-Benefit Paradox

The ultimate decision to terminate the contract was strictly economic. Malaysian officials determined that the event was simply too costly and was failing to provide sufficient financial returns to the country.

The figures were staggering: Malaysia was committing an estimated RM300 million per year solely for the hosting fee. Simultaneously, the crucial local metric—F1 attendance and ticket sales—was demonstrably dropping. When the immense annual expenditure was weighed against declining public interest and minimal discernible tourism return, the government concluded the funds could be better utilized elsewhere, specifically for athlete development and other national sports programs. The RM300 million figure per year provided an economically rational justification for ending the prestigious contract.

Economic Factors in the Malaysian Grand Prix Exit (Post-2017)

Factor | Data/Cost Magnitude | Impact on Contract Renewal |

Annual Hosting Fee | Estimated RM300 million (approx. $70M USD) | Deemed too high; yielded “no returns” to the country 2 |

Ticket Sales/Attendance | Documented decline starting mid-2010s | Decreased commercial viability and fan interest |

Regional Competition | Success of the Singapore Grand Prix (2008 onwards) | Divided the regional F1 market; Singapore offered a unique night race spectacle |

Government Priority Shift | Redirecting funds to athlete development | Minister confirmed costs could be better spent elsewhere |

The Shadow of Singapore

The competitive dynamic introduced by Malaysia’s nearest neighbor, Singapore, was a significant accelerating factor in Sepang’s decline. Since its inception in 2008, the Singapore Grand Prix provided F1 with a unique, high-glamour, centralized night race spectacle. This created intense regional competition for F1 fans, corporate sponsorships, and tourist dollars.

Sepang, which hosted its races in oppressive daytime heat and struggled with the chaotic scheduling of the 2009 sunset race, suddenly found itself competing with an event that offered a far greater novelty factor and a centralized tourism experience in the Marina Bay area. This competition likely exacerbated the decline in Sepang’s attendance, making the high annual hosting fee even more economically unjustifiable in the face of a superior regional product offering.

The decision to end the contract after the 2017 race was not a reflection on the quality of the circuit itself, but a cold assessment of the return on investment. The cost was too high, the appeal had decreased under the shadow of its neighbor, and the funds were needed for domestic priorities.

The Final Chapter and Lingering Nostalgia

The 2017 Malaysian Grand Prix served as the final chapter in the Sepang saga. Fittingly, the race was won by a driver who would quickly define the next generation of dominance, Max Verstappen of Red Bull Racing. His victory capped 19 years of Formula 1 history at the venue, concluding an era that began with the controversial debut of Schumacher and Irvine.

The Loss of a Masterpiece

For the F1 community, the departure of Sepang was a genuine loss. Motorsport experts consistently regard the track as an exceptionally challenging layout that fostered genuinely exciting racing, unlike many of the newer circuits that prioritize safety over driver challenge. Analysts like Matt Bishop praised Sepang as Tilke’s “finest” design, noting that F1 lost a stage defined by flowing corners and excellent overtaking opportunities. The dominance of champions like Vettel, Schumacher, and Alonso throughout the Sepang era confirms that the circuit provided a rigorous and worthy examination that separated the elite drivers from the rest of the field.

The closure of Sepang offers a profound cautionary tale regarding the aggressive commercial model of modern Formula 1. Even a structurally brilliant, driver-approved circuit—one built at immense national expense as a symbol of modernity—could not sustain the astronomical hosting fees when the initial novelty faded and regional competition arrived. The failure to secure the unique niche of a night race, particularly after the 2009 disaster, was a crucial missed commercial opportunity that might have secured its uniqueness against Singapore’s later success.

Legacy and Future Prospects

Today, the Sepang International Circuit remains operational and highly regarded, primarily serving as a venue for MotoGP and other international and national racing series. Its architectural genius endures, providing an excellent platform for two-wheeled racing which arguably thrives even more on the track’s width and flowing nature.

However, the prospect of Formula 1 returning to the circuit remains distant. In 2025, the Youth and Sports Minister confirmed that there are no immediate plans to reinstate the F1 Grand Prix. The rationale remains fixed: the prohibitive annual hosting fee, estimated at RM300 million, and the current congestion of the international race calendar make a return economically unfeasible for the government. The door remains open only under one specific condition: if private or corporate sponsors step forward to underwrite the massive hosting costs.

An Acknowledgment of Inspiration

This deeply researched narrative on Sepang’s journey was conceived with inspiration from the passion of – Makai Folsom, whose engaging motorsport content and dedication to F1’s rich, often-forgotten history reignited the interest in chronicling Sepang’s remarkable, complex story.

Conclusion

Sepang’s legacy is defined by its contradictions: an architectural masterpiece built on a swamp, a geopolitical symbol undone by a balance sheet, and a challenging track that ultimately fell victim to the economic realities of a sport increasingly dominated by spectacle over substance. It remains a nostalgic monument to Malaysian ambition and a reminder of the raw, physical drama that Formula 1 sometimes sacrifices in its relentless global expansion.