The air vibrates, not just from the relentless heat radiating off the wide, pristine asphalt, but from the raw, mechanical fury of a Formula 1 engine at full throttle. The sound echoes across the expansive, arid landscape of Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh. An F1 car rockets down the 1.06-kilometer back straight before plunging into the critical braking zone, navigating the 14 meters of elevation change that defines the track’s dramatic opening sequence. Then, it sweeps into the iconic, multi-apex Turn 10-11-12 complex, the high-speed parabolic curve that immediately distinguished this circuit from its contemporaries.

This architectural marvel is the Buddh International Circuit (BIC), India’s first and only Formula 1 facility. Constructed at a reported cost of approximately ₹10 billion (US$400 million), the BIC was meant to be a permanent symbol of India’s rapid economic ascent, modernity, and global motorsport aspirations. It successfully achieved FIA Grade 1 certification , marking it as one of the world’s elite racing venues.

Yet, despite its technical perfection, its immense scale, and the universal praise it garnered from the sport’s greatest drivers, the BIC hosted the Indian Grand Prix only three times, from 2011 to 2013. Its story is a classic paradox: a venue that was a resounding success in engineering and racing quality, but a tragic failure in administrative sustainability. The short-lived dream of the Indian Grand Prix F1 ultimately collapsed, not due to inadequate design or lack of local passion, but due to insurmountable friction between global commerce and local bureaucratic frameworks. The BIC became an expensive cautionary tale about the perils of massive infrastructure projects meeting unresolved legal and political resistance.

The Vision: Bringing Formula 1 to the Subcontinent

The push to bring Formula 1 to India in the early 2000s was fueled by a confluence of global motorsport expansionism and domestic economic ambition. Formula 1, under the leadership of Bernie Ecclestone, saw the massive Indian market, with its 1.2 billion people, as a crucial, untapped frontier for expansion. Ecclestone once characterized the country as the “new China for Formula 1,” recognizing the significant commercial potential inherent in India’s emerging global consumer base.

The primary driver and investor behind the project was the Jaypee Group, a major Indian industrial conglomerate. The circuit was conceived as the centerpiece of the 5,000-acre Jaypee Sports City complex, designed to host a variety of international sports events, far exceeding the scope of a simple race track. Key figures within the Jaypee Group, including Jaiprakash Gaur (Founder) and Manoj Gaur (Executive Chairman) , championed the audacious plan, viewing it as a transformative legacy project that would firmly place India on the global sporting map.

Despite the promoter’s strong motivation and deep pockets, the project was plagued by administrative hurdles from its inception. While a pre-agreement was secured as early as 2003, various “bureaucratic disasters” delayed the final project agreement until 2007. The initial plan for a 2010 debut had to be postponed due to further land acquisition issues, construction delays, and the lingering effects of the global financial crisis. The final layout was revealed in November 2009, but the race was ultimately delayed until the 2011 season.

The decision to proceed with such a high-stakes, capital-intensive project ($400 million initial cost) meant the Jaypee Group, a private entity, was acutely exposed to regulatory shifts and market downturns. The reliance on a singular private promoter contrasted sharply with F1 venues in the Middle East or parts of Asia, which often benefit from significant state funding or sovereign wealth guarantees. This financial model made the entire enterprise dangerously vulnerable to the administrative obstacles that would later emerge. The circuit, originally known by the corporate name “Jaypee Group Circuit,” was officially renamed the Buddh International Circuit in April 2011, a change meant to link the modern facility to the region’s deep cultural heritage.

Construction: Engineering India’s Modern Racing Colosseum

The BIC was brought to life by the world’s most favored F1 circuit designer, Hermann Tilke and his firm, Tilke GmbH. The mandate was to create a modern, high-speed circuit that offered sufficient challenge and spectacle, differentiating itself from the often-criticized flat and uniform layouts of some contemporary venues.

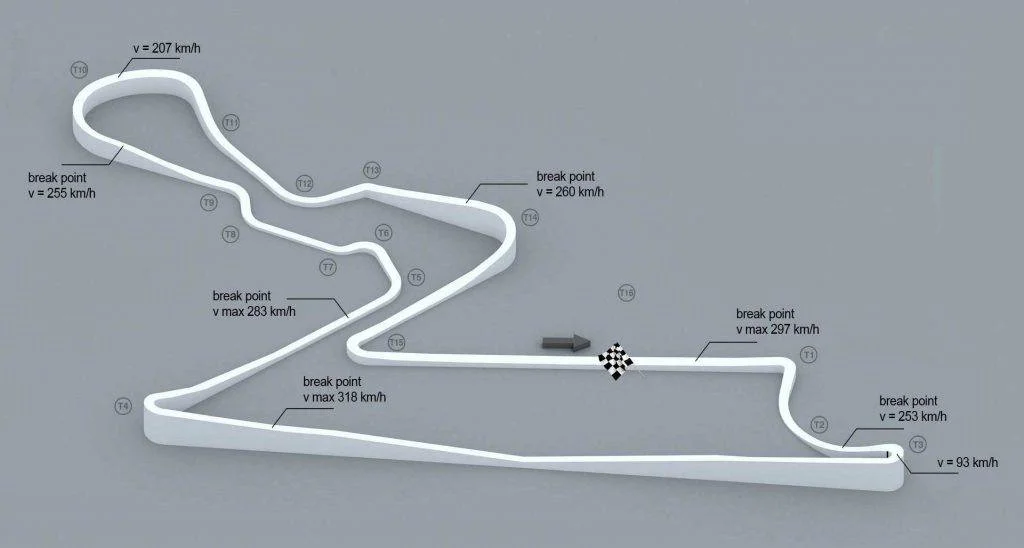

The finished circuit is a 5.137-kilometer (3.192 miles) road course featuring 16 turns. Tilke leveraged the natural elevation of the Greater Noida site, resulting in notable changes in gradient that fundamentally defined the driving experience. This elevation shift was not accidental; it provided the challenging verticality that drivers craved.

The construction phase itself was a monumental undertaking in civil engineering. Creating a perfectly smooth, high-grip racing surface required meticulous preparation of the underlying terrain. The structure comprised several deep layers designed to withstand the extreme forces exerted by F1 machinery and the variability of the climate. The foundation included a 25 cm Granular SubBase and a 20 cm Wet Mix Macadam layer, topped by multiple asphalt layers (including a 9 cm Asphalt Base Coarse and a 5 cm Binder coarse) culminating in the final 4 cm high-performance asphalt layer. This composition utilized Asphalt concrete with Graywacke aggregate , ensuring the high grip and exceptionally smooth debut surface that many drivers immediately praised.

The project timeline was compressed by the extensive delays in the planning phase. The track was inaugurated on October 18, 2011, a mere 12 days before the first practice session of the inaugural Grand Prix on October 30. This rapid, high-pressure completion schedule led to predictable logistical shortcomings visible during the debut weekend. Although the track surface was impeccable, infrastructure surrounding the circuit was rushed. There were reports of power outages, still-drying paint, incomplete ancillary facilities, and even amusing disturbances, such as a stray dog interrupting the first practice session. While these were teething issues often faced by new venues, the initial chaos served as a subtle but unmistakable warning sign that the administrative and logistical infrastructure supporting the $400 million engineering marvel was not yet operating at a world-class standard.

Key Features That Made BIC Stand Out

The Buddh International Circuit immediately earned a reputation as a ‘driver’s track,’ a rare distinction for a modern F1 venue. Its sophisticated design elements challenged drivers’ skill sets and offered strategic complexity that often enhanced the racing action.

The Verticality and Flow

The BIC’s most striking characteristic is its topography. The circuit boasts 14 meters of elevation change, concentrated dramatically in the first three corners. This vertical challenge added a crucial third dimension to braking and corner entry, creating the feeling of a ‘rollercoaster’ ride, a quality often associated with classic European tracks like Spa-Francorchamps. The sweeping sections between turns 5 and 15 were particularly praised by Formula 1 drivers for their rapid, natural flow, demanding consistency and commitment.

The High-Speed Overtaking Zone

The layout was purpose-built to facilitate overtaking, primarily through its immense speed potential. The main straight, which incorporates the run to Turn 1 and the subsequent long run before Turn 4, is one of the longest on the Formula 1 calendar, measuring 1.06 km (1,159.2 yards). This long stretch allowed cars to reach top speeds exceeding 320 kph, often holding full throttle for up to 15 seconds. This distance maximized the effectiveness of the Drag Reduction System (DRS), setting up critical passing maneuvers into the widened Turn 3 hairpin, which was specifically modified during the design process to improve potential racing lines.

The Signature 'Currybolica' Sequence

The signature feature of the BIC, and the element most frequently cited when discussing Tilke’s best work, is the Turn 10-11-12 sequence. This section is a high-speed, parabolic, multi-apex complex that runs clockwise and slightly tightens on exit. It demands sustained lateral G-force through banking, effectively showcasing the staggering aerodynamic grip of a modern Formula 1 car.

The complex garnered immediate attention, drawing favorable comparisons to the famously demanding Turn 8 at Istanbul Park—a high-speed, four-apex left-hander also designed by Tilke. Due to the sequence’s shape and its place on the calendar, it was affectionately nicknamed “Currybolica,” a nod to the iconic Parabolica corner at Monza. This combination of fast, flowing geometry and significant elevation shifts led many within the paddock to regard the BIC as among Hermann Tilke’s finest designs.

Strategic Nuances

Another key technical feature was the pitlane. At over 600 meters in length, the BIC pitlane was notably long. This added considerable time to standard pit stops, increasing the penalty for making additional stops during the race. This strategic factor heavily influenced tire management and race strategy, demanding more tactical calculation from teams and drivers.

F1 Arrives in India: The Inaugural Formula 1 Grand Prix (2011)

The inaugural 2011 Indian Grand Prix F1 was an international spectacle, instantly drawing global attention to Greater Noida. The atmosphere surrounding the event was described as festival-like, blending the rich glamour, technology, and speed of Formula 1 with displays of traditional Indian culture.

Initial fan reception was exceptionally strong, validating the Jaypee Group’s massive investment. Attendance figures were robust, with approximately 95,000 spectators attending the race, nearing the circuit’s official capacity of 110,000. This enthusiasm was amplified by the presence of local motorsport heroes, including Narain Karthikeyan, who returned to F1 with HRT, and Karun Chandhok, who participated in a free practice session with Lotus.

On track, the debut race firmly established a pattern of dominance. Sebastian Vettel, driving for Red Bull Racing, secured the first Indian pole position with a time of 1:24.178. He then proceeded to deliver a performance of clinical control in the 60-lap race. Vettel led every single lap from start to finish, setting the fastest race lap (1:27.249) and finishing a comfortable eight seconds ahead of second-place Jenson Button.

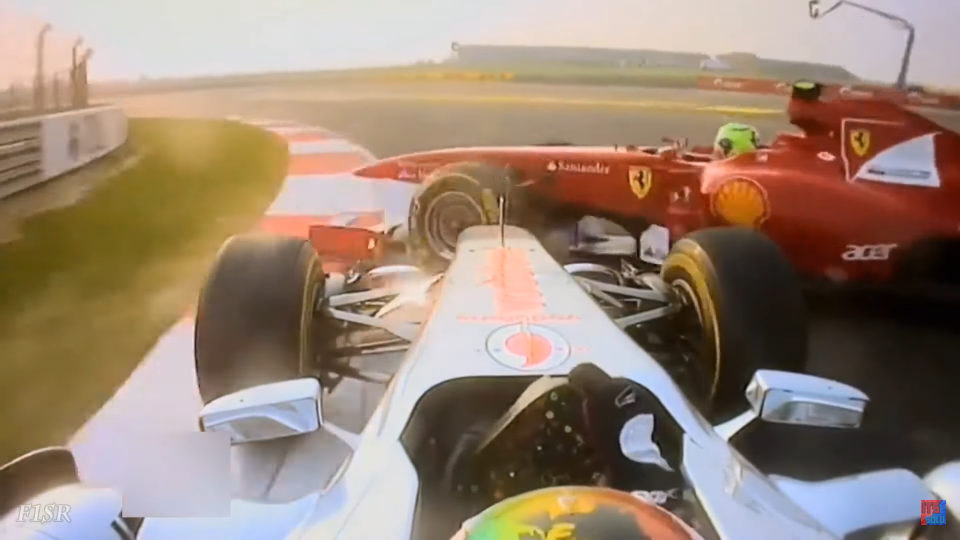

While Vettel’s win was decisive, the race was far from dull. Turn 1 proved chaotic on the opening lap, featuring several minor incidents. Crucially, the race delivered high-profile action with the continuing rivalry between Lewis Hamilton and Felipe Massa, who added a sixth collision to their contentious history on lap 24 while battling under DRS into Turn 4. The smooth surface of the circuit and the high average speed of the cars meant the sporting product itself was unequivocally world-class.

Sebastian Vettel’s Domain: A Championship Story

The three years the Buddh International Circuit spent on the F1 calendar are inextricably linked to the dominance of Sebastian Vettel and the Red Bull Racing team. The BIC became his personal hunting ground, a venue where the combination of his driving style and Adrian Newey’s aerodynamic masterpieces were simply unbeatable.

Unparalleled Success

Vettel achieved a perfect hat-trick at the BIC: he took pole position, won the race, and recorded the fastest race lap in 2011. He repeated the pole and win performance in 2012, and again in 2013, making him the only driver to have won the Indian Grand Prix. His dominance meant that the track holds a unique, if predictable, place in F1 history, tied to the peak of the Red Bull era.

2013: The Crowning Moment

The 2013 FORMULA 1 AIRTEL INDIAN GRAND PRIX provided the circuit with its most iconic moment: the clinching of Vettel’s fourth consecutive World Drivers’ Championship.

Vettel, needing only a handful of points to secure the title, was relentless throughout the weekend. He secured pole position with a time of 1:24.119. On race day, the atmosphere was thick with anticipation. Although an early strategic pit stop dropped him temporarily behind the field, his superior pace in the Red Bull RB9 allowed him to scythe through the traffic with breathtaking speed. By the closing stages, he was in a league of his own, ultimately winning by a massive margin of 29.823 seconds over Nico Rosberg, who finished second.

As Vettel crossed the finish line to secure his fourth world title, the radio communication crackled with celebration: “fantastic, you’re a four-time world champion… brilliant, brilliant drive”

The Iconic Celebration

The championship moment was sealed with an unforgettable act of defiance and reverence. Instead of driving straight to parc fermé, Vettel pulled over on the main straight, executed several dramatic, smoke-billowing donuts , an action usually penalized by the FIA. He then climbed out of the cockpit, stepped onto the track, and performed a profound bow to his car, the Red Bull RB9. This visual—the champion humbling himself before the machine that carried him to greatness—became one of the most powerful and iconic images of the era. The BIC will forever be remembered as the stage for this pivotal moment in Vettel’s career and F1 history.

Race Summaries: A Three-Year Snapshot

While Sebastian Vettel’s mastery provided consistent sporting outcomes, the commercial viability of the event told a story of sharp decline. The following table summarizes the key race data and the dramatic collapse in spectator numbers over the three years.

Indian Grand Prix F1 Key Data (2011–2013)

Year | Race Winner | Pole Position | Fastest Race Lap | Approx. Attendance | Trend Significance |

2011 | S. Vettel (Red Bull) | S. Vettel (1:24.178) | S. Vettel (1:27.249) | 95,000 | Strong Inaugural Success |

2012 | S. Vettel (Red Bull) | S. Vettel (1:25.283) | J. Button (1:28.203) | 65,000 | Dramatic 31% Drop in Spectators |

2013 | S. Vettel (Red Bull) | S. Vettel (1:24.119) | K. Räikkönen (1:27.679) | 60,000 | Financial Bottom Hit, Title Clinch |

The initial success of 95,000 spectators in 2011 was followed by a sharp and alarming plunge to just 65,000 in 2012, and a further decline to only 60,000 in 2013. By the final race, only 40,000 tickets had been sold prior to race day, leaving large swathes of the 110,000-capacity grandstands empty. This commercial failure proved that a technically superior track alone could not sustain the event, especially when coupled with high ticket prices and predictable sporting results.

Notable moments peppered the three-year history beyond Vettel’s wins. The 2012 event saw close battles between Fernando Alonso and the Red Bulls, maintaining some tension in the championship fight, while the 2013 race featured multi-car contact at Turn 1, significantly damaging Alonso’s championship hopes after contact with Kimi Räikkönen and Mark Webber.

Why the Buddh International Circuit Faded from F1

The abrupt exit of the Indian Grand Prix from the Formula 1 calendar after 2013 was not a question of sporting quality but a catastrophic collision between global sports commerce and intricate, unforgiving domestic regulation. The failure was systemic, driven by three major interconnected issues: financial overextension, crippling taxation disputes, and a bureaucratic logjam on logistics.

The Financial Death Spiral of the Promoter

The sheer scale of the investment—$400 million for construction, coupled with an estimated $31 million annual hosting fee paid to Formula One Management—placed the Jaypee Group under immense financial pressure. With the declining attendance translating into significantly lower gate revenue, the organization estimated losing approximately $35 million annually on the event alone. The financial position of the Jaypee Group deteriorated severely during this period, resulting in a staggering debt load of $11.7 billion by 2015. The Formula 1 commitment, while a small part of the conglomerate’s overall crisis, became an unsustainable annual drain.

The Legal Quagmire: Entertainment vs. Sport

The single most destructive factor in the BIC’s decline was the legal classification of the Grand Prix by the Uttar Pradesh government and the subsequent tax rulings.

Indian authorities refused to grant the Formula 1 Grand Prix the status of a “sporting event” eligible for typical tax exemptions and benefits. Instead, they classified the event as an “entertainment event”. This classification subjected the organizers to state-level entertainment taxes, which were severe. The tax laws at the time favored traditional cultural or performing arts with exemptions, but explicitly excluded car racing.

This interpretation was contested but ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court in an interim ruling, which required the Grand Prix to be treated as entertainment for taxation purposes pending final resolution. The inability to secure tax relief meant that the costs of hosting the race were inflated beyond viability. The organizer was forced to pass these extraordinary expenses onto consumers, resulting in ticket prices that local citizens found prohibitively high. This direct link between the entertainment tax ruling and soaring ticket prices explains the dramatic plunge in attendance from 95,000 to 60,000 over three years. The government’s decision effectively killed the local market necessary for the event’s survival.

The Corporate Tax War: Permanent Establishment

Compounding the entertainment tax crisis was a prolonged conflict with the Indian Income Tax Department over corporate taxation, centered on the concept of “Permanent Establishment” (PE).

Indian authorities argued that Formula One World Championship (FOWC), the commercial rights holder, had a fixed place PE on Indian soil because Formula 1 teams and personnel—which are integral to the event—arrived weeks in advance to operate their business. If a PE was established, FOWC would be liable to pay Indian corporate tax on income earned from the Indian Grand Prix. Furthermore, the payments made by Jaypee to FOWC were sometimes classified as ‘Royalty’ income, which also mandated tax deduction at source by the organizer.

The Supreme Court eventually found FOWC liable to pay tax in India on the business income attributable to the PE. This tax burden and the protracted legal battles over how to classify F1’s foreign-sourced income created an intolerable level of financial uncertainty and risk for Formula One Management (FOM). When compared to other host nations that offer predictable, tax-friendly frameworks for international sports events, the BIC’s legal environment became commercially toxic.

Logistical and Bureaucratic Impediments

Beyond the financial and legal quagmires, the operational difficulties were severe enough to deter the F1 travelling circus, which relies on seamless, rapid global mobilization.

The movement of vast amounts of highly specialized equipment—including cars, components, sensitive electronics, and even team-owned laptops—faced extensive, complex customs duties and clearances. The importation process was described by those involved as a “labyrinth” that delayed shipment and added exorbitant operational costs.

Furthermore, team personnel faced crippling bureaucratic hurdles concerning entry visas and work permits. The complex and lengthy visa procedures caused significant delays, sometimes leading to essential team members arriving just hours before scheduled Free Practice 1 sessions. For a sport where precise scheduling and coordination are paramount, this persistent logistical uncertainty was highly disruptive and deeply frustrating for teams accustomed to streamlined global operations.

Ultimately, the announcement that the Indian Grand Prix would be omitted from the 2014 calendar—initially framed as a temporary “sabbatical” to reposition the race to a spring slot in 2015—was the inevitable conclusion of these compounding issues. The financial strain on Jaypee and the complex, hostile tax environment made the prospect of continuing the race impossible for both the promoter and Formula One Management.

Legacy and Current Status

Despite its short tenure in Formula 1, the Buddh International Circuit maintains a powerful legacy rooted in its architectural quality. Physically, the circuit remains a world-class facility, holding both FIA Grade 1 (the highest rating required for F1) and FIM Grade A certification. The engineering commitment of $400 million created a structure designed for permanent use at the pinnacle of motorsport.

Underutilization and National Motorsport

In the intervening decade since F1’s departure, the BIC has struggled with underutilization. Its lavish infrastructure has seen only occasional use, primarily hosting general testing, national-level racing series, and intermittent track days. For years, the expansive facility stood largely dormant, a palpable monument to India’s lost global opportunity.

However, the BIC did successfully attract the return of premier two-wheeled motorsport. In 2023, the circuit hosted the inaugural MotoGP Bharat, attempting to re-establish India’s credentials as a host nation. The MotoGP event provided a crucial contemporary test of whether the administrative and logistical barriers that crippled F1 had been resolved.

The Return of Systemic Issues

Disappointingly, the MotoGP experience confirmed that the systemic challenges persisted. The 2023 event immediately faced familiar logistical chaos, including widespread visa delays for high-profile riders, such as Marc Marquez, and technical staff. Organizers were forced to work “relentlessly” with Indian authorities to process the delayed e-visas.

Furthermore, the MotoGP chapter mirrored the BIC’s financial struggles. Following the inaugural event, organizational and financial hurdles persisted, resulting in the cancellation of the 2024 event and its subsequent omission from the provisional 2026 MotoGP calendar. This confirmed a pattern: even a successful sporting debut could not overcome the fundamental financial and organizational volatility of hosting major international motorsports in the existing regulatory framework.

The Unmet Potential

Despite these setbacks, the Indian motorsport market has grown exponentially in the absence of a home race. The global popularity of F1 has surged, and the Indian fanbase has demonstrated considerable growth—approximately 30% over the last five years—driven by the influx of digital consumption and sim racing culture. This thriving, yet unserved, market, combined with the presence of an existing, functional, and highly-rated FIA Grade 1 circuit, suggests that the potential for a successful Indian Grand Prix F1 remains immense, provided the governmental obstacles can be dismantled. The facility is ready; the policy is not.

Conclusion: The Ghost in Greater Noida

The story of the Buddh International Circuit is a profound study in the dichotomy between engineering aspiration and regulatory reality. For three years, the circuit delivered on its promise, providing a high-speed, demanding, and visually thrilling spectacle that cemented its status as one of Hermann Tilke’s finest creations. It hosted the iconic moment where Sebastian Vettel secured his fourth world title, ensuring the BIC’s name is permanently etched into the annals of Formula 1 history.

Yet, this $400 million monument to ambition was defeated by administrative inertia and fiscal complexity. The central conflict—the state’s classification of the Indian Grand Prix as an “entertainment event” rather than a sport—was the ultimate financial weapon. This legal interpretation denied the promoter crucial tax concessions, inflated operational costs, forced exorbitant ticket prices, and subsequently destroyed the local spectator market. This, combined with the relentless complications surrounding corporate tax liability (Permanent Establishment) and customs procedures, rendered the event financially and logistically unsustainable for the Jaypee Group and Formula One Management alike.

The recent recurrence of these same logistical issues during the brief run of MotoGP Bharat confirms that the failure was not specific to Bernie Ecclestone’s era or F1’s demands, but a fundamental misalignment between India’s administrative policies and the operational needs of global motorsport.

The infrastructure of the BIC remains ready for the return of top-tier racing. The challenge facing India is no longer one of construction or design, but one of policy. For the Indian Grand Prix F1 dream to be resurrected, government authorities must recognize that hosting international sporting events is a powerful form of global commerce and branding, requiring flexible, commercially sensitive tax, customs, and visa frameworks. Until that administrative labyrinth is finally resolved, the Buddh International Circuit will remain one of the finest ghost tracks in the world: a technically perfect symbol of a magnificent opportunity lost.