Williams Racing stands as one of Formula 1’s most iconic and historically significant teams. From its humble origins, it ascended to become a veritable behemoth of the sport, rivaled only by Scuderia Ferrari and McLaren in terms of sustained success. The team has amassed a remarkable nine Constructors’ World Championships, seven Drivers’ World Championships, and an impressive 114 Grand Prix victories. This extraordinary record places Williams joint second in Constructors’ titles and third in all-time Grands Prix entered.

At the heart of this formidable legacy was the sheer brilliance and unwavering passion of its late founder, Sir Frank Williams. His indomitable spirit forged a team renowned for its resilience, engineering prowess, and a relentless pursuit of victory against all odds. However, the narrative of Williams Racing is not merely one of past glory. It is also a compelling story of evolution, adaptation, and the profound challenges faced in a sport that constantly reinvents itself. The journey from a dominant force to a team navigating the complexities of modern Formula 1 underscores that even the most celebrated entities must continuously innovate and adapt to remain at the pinnacle of global motorsport.

Humble Beginnings: Frank Williams Racing Cars (1966-1976)

The genesis of Williams Racing can be traced back to 1966, when Frank Williams, following a brief career as a driver and mechanic, founded Frank Williams Racing Cars (FWRC). His initial foray into team ownership was funded by his own earnings as a grocery salesman, a testament to his profound personal commitment to motorsport. FWRC began by running cars in Formula 2 and Formula 3 before making its Formula 1 debut in 1969. Frank purchased a Brabham chassis for his close friend, Piers Courage, who impressively secured two second-place finishes that season. Frank recognized Courage’s “serious talent,” and these early successes hinted at the potential of the fledgling operation.

However, the early 1970s brought immense hardship. A partnership with chassis manufacturer De Tomaso in 1970 ended tragically with Courage’s death at the Dutch Grand Prix. Frank was “devastated,” recalling that “life got very tough the next day”. This profound personal loss likely transformed his motivations for racing, shifting it from a purely enjoyable pursuit to a more driven, perhaps even grim, commitment to success, honoring the sacrifices made. The period was also marked by severe financial struggles. Frank was often “scraping a living,” at one point even operating his team business from a public telephone box because he “couldn’t pay the bloody bill!” and frequently relied on loans from Bernie Ecclestone. In 1972, the team’s first self-built F1 car, the Politoys FX3, designed by Len Bailey, was destroyed in a crash during its inaugural race. This relentless cycle of challenges, from financial precarity to personal tragedy, hardened Frank Williams, forging an unparalleled resilience and determination that would define the team’s character for decades.

Financial stability, albeit temporary, arrived in 1976 when Austro-Canadian oil magnate Walter Wolf acquired a majority shareholding in Frank Williams Racing Cars. While Frank remained an employee, the team no longer belonged to him, a situation he “didn’t enjoy”. The cars under Wolf’s ownership remained uncompetitive. This loss of autonomy over his racing destiny was intolerable for Frank, serving as the direct catalyst for him to sever ties and embark on a new, independent venture. His unwavering desire for control over his team’s direction would become a defining characteristic.

The Birth of a Dynasty: Williams Grand Prix Engineering (1977)

In 1977, driven by his unyielding vision, Frank Williams departed Walter Wolf Racing to establish Williams Grand Prix Engineering (WGPE). This pivotal moment was marked by the crucial recruitment of engineer Patrick Head, whom Frank convinced to join him in this audacious new enterprise. This partnership proved to be a stroke of genius, creating a symbiotic relationship where Frank’s relentless drive for funding and overall team management perfectly complemented Head’s formidable engineering capabilities. This clear division of labor, with Frank as the visionary leader and Head as the technical architect, provided the balanced leadership essential for rapid growth and success.

WGPE was officially incorporated on February 8, 1977, initially under the name LATCADE LIMITED. Their new headquarters was an empty carpet warehouse in Didcot, Oxfordshire, a testament to their humble beginnings. The team’s first Formula 1 appearance as WGPE was at the 1977 Spanish Grand Prix, where they ran a March chassis for Patrick Nève. Despite competing in 11 races that year, the new team failed to score a point, with a best finish of seventh.

Recognizing the limitations of customer cars, Williams made a strategic decision to begin manufacturing its own chassis the following year. The FW06, their first in-house car, debuted at the 1978 Argentine Grand Prix. This commitment to self-sufficiency and technical independence, largely driven by Head’s conviction that they “needed our own car”, was a critical step towards becoming a true constructor and laid the groundwork for their future technical dominance. Frank also bolstered the technical team by bringing in talents like Neil Oatley as a cartographer and Frank Dernie, who contributed expertise in suspension geometry, aerodynamics, and early computer programming.

Early Breakthroughs and First Titles (1979-1982)

The FW07, designed by Patrick Head, proved to be a game-changer. Crucial aerodynamic refinements by Head and Frank Dernie before the 1979 British Grand Prix marked the decisive breakthrough. At their home race in Silverstone, Clay Regazzoni, driving the Cosworth-powered Williams FW07, secured the team’s first Formula 1 victory. This rapid ascent, from a new team struggling for points in 1977 to a Grand Prix winner in just two years, vividly demonstrated the effectiveness of the Frank-Head partnership and their focused engineering approach.

Williams’ rise in Formula 1 was nothing short of “meteoric”. After finishing as the Constructors’ Championship runner-up in 1979, the team achieved a stunning double triumph in 1980, securing both its first Drivers’ and Constructors’ championships. Australian Alan Jones clinched the Drivers’ title with five Grand Prix victories in the FW07B, and the team dominated the Constructors’ standings by an impressive 54 points. The FW07B itself was a product of relentless development, boasting 30% more downforce than its predecessor, a testament to the continuous innovation driven by Patrick Head and chief aerodynamicist Frank Dernie. The Cosworth DFV engine, enhanced by John Judd, further contributed to this formidable package. This period firmly established Williams’ reputation for engineering excellence and a commitment to iterative improvement.

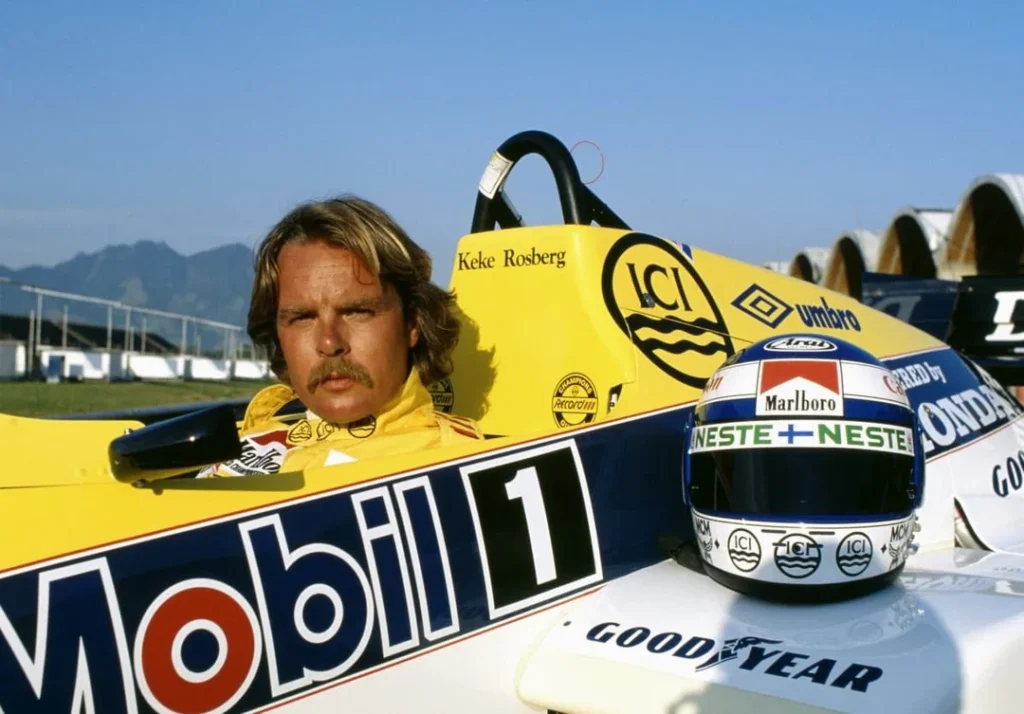

The team’s success continued into 1981, as Williams secured its second consecutive Constructors’ title, amassing 95 points with Alan Jones and Carlos Reutemann each contributing two race victories. In 1982, Keke Rosberg famously won the Drivers’ Championship with Williams despite recording only a single race win throughout the season. This unique achievement underscored the team’s ability to maintain consistency and capitalize on opportunities even in a highly competitive and often chaotic season. It also highlighted their resourcefulness in maximizing the performance of their customer Cosworth engine package against more powerful rivals.

The Turbo Era: Honda Power and Intense Rivalries (1983-1987)

The mid-1980s saw Williams strategically transition to Honda turbo engines. While it took some time for the partnership to fully gel, it eventually delivered immense success. This period also brought one of the most profound personal challenges for Frank Williams. In March 1986, a devastating road accident left him paralysed. Despite this life-altering event, Frank’s “astonishing self-discipline” and pragmatic attitude, encapsulated by his question, “How am I going to get out of this?” kept him at the helm. The unwavering support of his wife, Ginny, was crucial to his recovery and, by extension, to the team’s survival. This remarkable display of resilience from its founder permeated the entire team, demonstrating that Williams’ strength was deeply rooted in its human spirit.

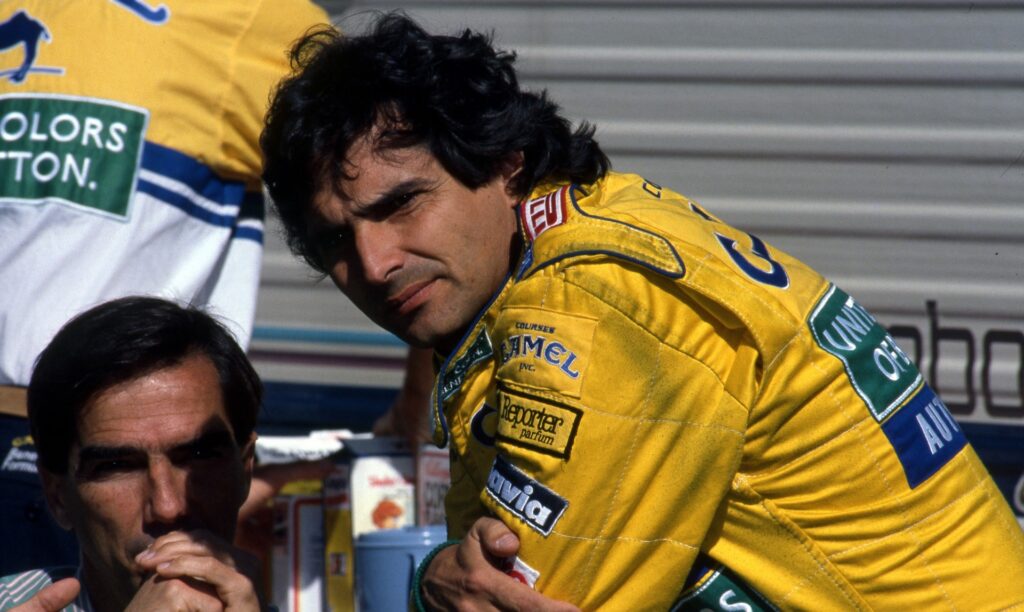

In 1986, the Williams-Honda FW11 was widely regarded as the “state of the art F1 car”. Its immensely powerful Honda engine allowed the team the luxury of running more aggressive aerodynamic setups, complemented by a well-engineered carbon-fibre chassis. The team secured nine Grand Prix victories and the Constructors’ Championship that year. However, the Drivers’ Championship narrowly eluded Nigel Mansell due to a dramatic tyre burst in the final race in Australia. The 1986 and 1987 seasons were also defined by an “increasingly bitter intra-team rivalry” between Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet. While this intense competition created internal friction, it also pushed both drivers and the team to extract every ounce of performance from their dominant machinery, ultimately contributing to Williams’ back-to-back Constructors’ championships in 1986 and 1987. This dynamic illustrated how competitive tension, when contained within a strong technical framework, can be a powerful accelerant for on-track success.

For the 1987 season, Williams introduced the improved FW11B. The Honda RA167E V6 turbo engine for that year was a marvel of engineering, achieving an “outlandish output of over 1000 hp”. This period highlighted that dominance in the turbo era was heavily reliant on securing a superior engine and then meticulously designing the car around it. From mid-season onwards, the team was unstoppable, winning race after race and clinching its second consecutive Constructors’ title. Nelson Piquet secured his third Drivers’ Championship. A particular highlight was Nigel Mansell’s “scintillating late race charge” to beat Piquet at Silverstone, a moment that further fueled the phenomenon known as “Mansellmania”. It is also noteworthy that the FW11 was the first Williams car designed using CAD-CAM (computer-aided design – computer-aided manufacture), showcasing the team’s early adoption of advanced design tools.

The Renault Partnership and Adrian Newey's Masterpieces

The seeds of Williams’ recovery from the loss of Honda engines were sown in 1989 with a strategic switch to Renault power. This partnership would usher in Williams’ most dominant era. Renault engines subsequently powered Williams’ drivers to an astonishing four Drivers’ and five Constructors’ Championships, making Renault their most successful engine supplier and the cornerstone of their 1990s supremacy.

A pivotal moment in this golden age was the arrival of Adrian Newey in 1990, who took over from Frank Dernie. Newey’s decision to join Williams was partly influenced by the team’s robust funding, which provided the necessary resources to develop groundbreaking ideas such as active suspension. This illustrates a critical dynamic in Formula 1: the ability of well-resourced teams to attract and retain the sport’s brightest technical minds, thereby accelerating their competitive advantage. The combination of Renault’s powerful engines and Adrian Newey’s unparalleled designing expertise created an almost unbeatable package, leading to Williams’ unrivalled dominance throughout the mid-1990s.

Newey’s impact extended far beyond individual Williams cars; he fundamentally reshaped Formula 1 car design. His pioneering work on the March 881 in 1988 effectively prototyped the aerodynamically-driven F1 cars that followed, introducing innovations like the fully integrated nose/front wing assembly and complex three-dimensional endplates. He also significantly evolved the reclined driver seating position, which became an industry standard for optimizing aerodynamics and packaging within the car. These advancements demonstrate how Williams, through Newey’s vision, was at the forefront of fundamental shifts in F1 car design philosophy, influencing the entire sport for decades.

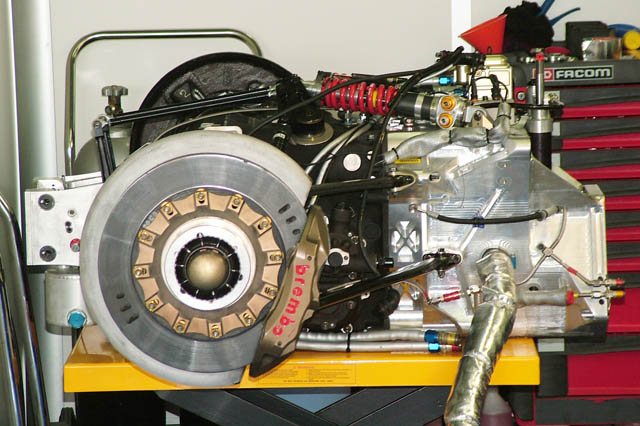

The FW14B (1992), a masterpiece designed by Patrick Head and Adrian Newey, was “far superior” to its rivals and “packed with innovative advancements,” most notably its active suspension system. While Lotus had experimented with active suspension earlier, Williams perfected the technology, giving the FW14B a decisive competitive advantage. The car’s sophisticated electronic systems managed its suspension, engine, gearshifts, and traction control via CAN bus. This technological edge allowed Williams to often qualify “a second ahead of their closest challenger”. Williams’ commitment to pushing technological boundaries, even with systems that would later be outlawed for performance reasons, underscored their innovative spirit and their relentless pursuit of every possible performance gain.

Williams F1 World Championships

The following table provides a concise overview of Williams Racing’s formidable championship record, highlighting their periods of dominance and the legendary drivers who contributed to their success.

Year | Constructors’ Champion | Drivers’ Champion |

1980 | Yes | Alan Jones |

1981 | Yes | No |

1982 | No | Keke Rosberg |

1986 | Yes | No |

1987 | Yes | Nelson Piquet |

1992 | Yes | Nigel Mansell |

1993 | Yes | Alain Prost |

1994 | Yes | No |

1996 | Yes | Damon Hill |

1997 | Yes | Jacques Villeneuve |

This table visually encapsulates Williams’ golden era, particularly the 1990s, where their engineering prowess and driver talent combined to deliver an almost unbroken string of titles. It underscores the team’s consistent ability to produce championship-caliber machinery and attract the world’s best drivers.

Key Architects of Success: The People Behind the Glory

Sir Frank Williams: The Indomitable Spirit

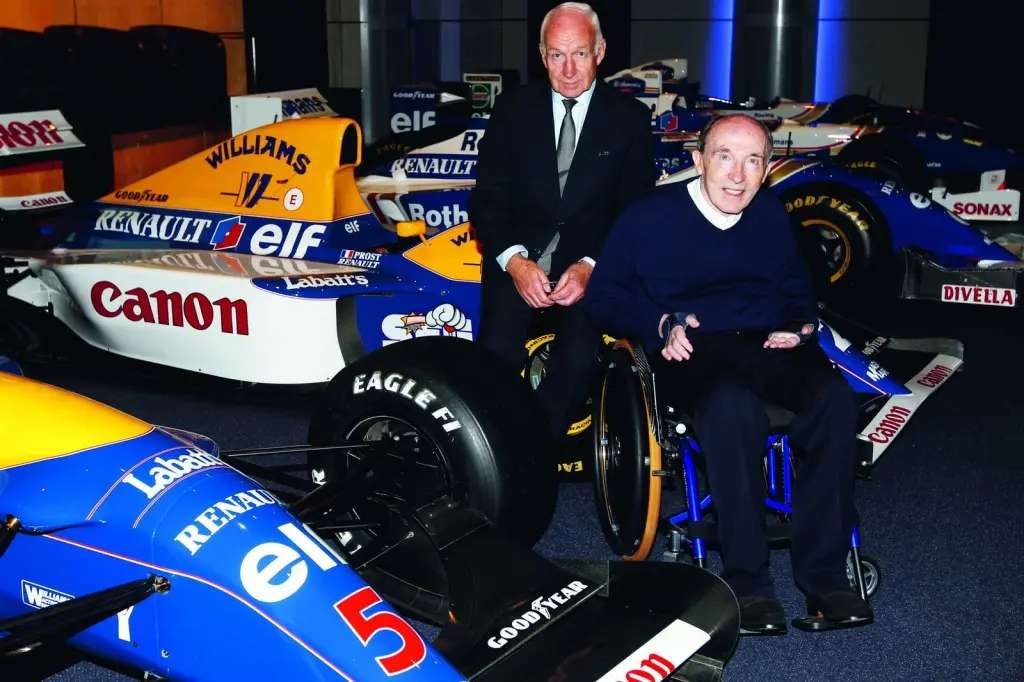

Sir Francis Owen Garbett Williams (1942–2021) was the very soul of Williams Racing, serving as its co-founder, team principal, and co-owner from 1977 until 2020. His career was defined by an “unwavering dedication,” “astonishing self-discipline,” and an immense “energy and enthusiasm” that Patrick Head identified as his most outstanding qualities. These personal attributes were the bedrock upon which the entire team’s identity was built.

Frank faced extraordinary personal and financial challenges throughout his journey. From operating his team from a public telephone box due to unpaid bills to the life-altering road accident in 1986 that left him paralysed, his resilience was tested repeatedly. Yet, he continued to lead the team, with his wife Ginny playing a “pivotal role” in his recovery and the team’s continued existence. His ability to not only survive but thrive despite such profound personal adversity showcased a leadership style rooted in sheer force of will, transforming him into a legendary figure whose personal battles seemed to mirror and even fuel the team’s on-track resilience.

His contributions to motorsport were recognized with numerous accolades, including being appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1987, receiving a knighthood in 1999 for “services to the Motor Sport Industry,” and being made a Knight of the Legion d’honneur by France for his work with Renault engines. The Frank Williams Memorial Trophy at the Silverstone Classic now stands as a tribute to his enduring legacy.

Under his leadership, Williams Racing achieved all 9 Constructors’ and 7 Drivers’ Championships, along with 114 Grand Prix victories. Frank gradually stepped back from direct involvement, first from the board in 2012 (replaced by his daughter Claire Williams) and eventually ceasing all involvement with the team’s sale in September 2020. This transition marked the poignant end of an era for the “privateer” model in Formula 1, acknowledging that the sport’s evolving economics and scale eventually necessitated a change in ownership structure, making his earlier achievements even more remarkable.

Sir Patrick Head: The Engineering Maestro

Sir Patrick Head was the indispensable technical counterpart to Frank Williams, co-founding Williams Grand Prix Engineering in 1977. While Frank focused on securing funding and managing the team, Head was responsible for its design and operations, where he was “strong on the engineering side”. This complementary partnership was absolutely essential for translating Frank’s ambitious vision into tangible on-track success.

Head’s genius was evident from the outset, particularly in his “pioneering work on the Williams FW07”. His innovative underbody ground-effect design was a breakthrough that “fundamentally changed the design of Formula One cars,” setting new standards for aerodynamic efficiency. This foundational design propelled the team to its first successes, including their first Grand Prix win in 1979 and their maiden World Championship in 1980. Head’s technical leadership was instrumental in the design of cars that collectively claimed all 9 Constructors’ and 7 Drivers’ titles under Williams’ banner. His early designs established a culture of relentless engineering innovation that became a hallmark of Williams’ golden age, proving that behind every great team principal, there is often an equally brilliant, though perhaps less publicly recognized, technical director whose innovations truly drive performance.

Adrian Newey: The Aerodynamic Visionary

Adrian Newey, widely regarded as one of Formula 1’s greatest designers, joined Williams in 1990, taking over from Frank Dernie. His decision to move to Williams was partly influenced by the team’s superior funding at the time, which provided the necessary resources to develop advanced concepts such as active suspension. This highlights a crucial aspect of Formula 1: the ability of well-resourced teams to attract and retain the brightest technical minds, thereby accelerating their competitive advantage.

Newey’s “designing expertise,” combined with Renault’s powerful engines, proved to be the catalyst for Williams’ unparalleled dominance throughout the mid-1990s. His impact, however, extended far beyond the immediate success of Williams. Newey’s work on the March 881 in 1988 had already established the template for aerodynamically-driven F1 cars, introducing innovations like the fully integrated nose/front wing assembly and complex three-dimensional endplates. Furthermore, he significantly evolved the reclined driver seating position, which became an industry standard for optimizing aerodynamics and packaging within the car. These innovations demonstrate how Williams, through Newey’s vision, was at the forefront of fundamental shifts in F1 car design philosophy, influencing the entire sport for decades to come by pushing the boundaries for all competitors.

Legendary Drivers: Profiles and Triumphs

Over its storied history, Williams Racing has been a crucible for some of Formula 1’s most legendary drivers, many of whom achieved their greatest triumphs while donning the distinctive blue and white livery.

Nigel Mansell: "Il Leone" and Red 5

Nigel Mansell, a British icon, was characterized by his “hugely determined, immensely aggressive and spectacularly daring” driving style, often described as a “win or bust approach”. His journey to the top was marked by fierce competition and unforgettable moments. His first Grand Prix victory came with Williams at the 1985 European Grand Prix, a moment that ignited the widespread phenomenon of “Mansell Mania”. After narrowly missing the 1986 championship due to a dramatic tyre failure, he delivered a scintillating performance at Silverstone in 1987, famously beating Nelson Piquet and “kissing the tarmac” in celebration. Mansell’s crowning achievement arrived in 1992, where he utterly dominated the season, securing nine victories in the iconic “Red 5” FW14B and clinching the World Championship with five races to spare. His departure from F1 for IndyCar immediately after his title, driven by financial disputes and the prospect of Alain Prost as a teammate, highlighted the intense personal and professional dynamics that could exist even within a championship-winning team. Mansell holds the unique distinction of being the only driver to have simultaneously held both the F1 World Drivers’ Championship and the American open-wheel National Championship, which he achieved after winning the IndyCar title in 1993.

Alain Prost: The Professor's Final Masterpiece

Alain Prost, universally known as “The Professor” for his cerebral and strategic approach to racing, made a highly anticipated return to Formula 1 with Williams in 1993 after a year-long sabbatical. Prost’s season was a masterclass in consistency and efficiency. He secured seven race victories, broke several records, and ultimately claimed his fourth World Championship before announcing his retirement from the sport at the end of the season. His triumph exemplified how a driver of immense experience and strategic acumen could perfectly leverage the advantages of a technologically superior car, culminating in a fitting end to a legendary career.

Nelson Piquet: The Artful Strategist

Nelson Piquet, a three-time World Drivers’ Champion, added his 1987 title to Williams’ growing tally. His period at Williams was marked by an intense, often bitter, rivalry with teammate Nigel Mansell. While challenging for team harmony, this fierce internal competition pushed both drivers to their absolute limits, extracting every ounce of performance from the dominant Honda-powered machinery and ultimately contributing to the team’s back-to-back Constructors’ titles.

Damon Hill: Carrying the Torch

Damon Hill, the son of two-time World Champion Graham Hill, began his journey with Williams as a test driver in 1992 before being promoted to a race seat in 1993. He secured his first Grand Prix victory at the 1993 Hungarian Grand Prix. Following the tragic death of Ayrton Senna in 1994, Hill courageously stepped up to lead the team, playing a crucial role in rebuilding morale and delivering strong performances under immense pressure. His intense championship battles with Michael Schumacher, including the controversial 1994 title decider, became a defining narrative of the mid-90s.34 Hill finally clinched the Drivers’ Championship in 1996 with eight wins. However, despite achieving the ultimate success, Williams controversially decided to drop him for 1997, a decision that underscored the demanding and often unsentimental nature of top-tier motorsport.

Jacques Villeneuve: The Fearless Finisher

Jacques Villeneuve, the charismatic son of legendary Gilles Villeneuve, made an immediate and impactful F1 debut with Williams in 1996, taking pole position in his very first race in Australia and finishing second to Damon Hill. In 1997, Villeneuve delivered on his immense promise, securing seven race victories and claiming the Drivers’ title after a “notorious championship showdown” with Michael Schumacher at Jerez. His fearless driving style and willingness to take risks, often reminiscent of his father, made him a captivating figure on the grid. Villeneuve was also one of the few Williams champions, alongside Alan Jones and Keke Rosberg, to defend his title while still with the team.

Beyond the Track: Innovation and Technology Transfer

Williams Racing has a rich history of pushing the boundaries of technological innovation within Formula 1, often leading the field with groundbreaking advancements.

Active Suspension: One of Williams’ most significant technological triumphs was the development and perfection of active suspension, particularly on the FW14B in 1992. While Lotus had experimented with the concept earlier, Williams refined it to provide a decisive competitive advantage, allowing the car to maintain optimal ride height and aerodynamic efficiency regardless of track conditions. This sophisticated system, which managed suspension, engine, gearshifts, and traction control via CAN bus, was so effective that it was eventually outlawed by the sport’s governing body to curb dominance and increase driver skill emphasis. This exemplifies Williams’ willingness to invest in and exploit advanced systems, even if it meant their innovations were eventually restricted.

Aerodynamics: Williams maintained a consistent focus on maximizing downforce and efficiency through continuous innovation in aerodynamics. From Patrick Head and Frank Dernie’s early work on ground effect with the FW07, which fundamentally reshaped car design, to Adrian Newey’s transformative designs that set industry-wide templates for integrated front wings and driver packaging, Williams consistently pushed the envelope of aerodynamic performance.

Hybrid Systems: Williams also played a significant role in the development of hybrid technology in motorsport through Williams Hybrid Power (WHP). This originated from F1’s Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems (KERS) development, introduced as an optional technology in 2009. Although Williams ultimately elected not to use their flywheel-based KERS in their F1 cars due to packaging issues, the underlying technology proved too valuable to discard.

Pioneering Collaborations with Engine Suppliers

Williams’ success has often been intertwined with its strategic partnerships with engine manufacturers, each collaboration marking a distinct era in the team’s history.

Cosworth (Early Years): In its formative years and during its first championship triumphs, Williams relied on Cosworth engines. These reliable and relatively cost-effective customer units allowed Williams to establish itself as a formidable force, demonstrating the team’s ability to extract maximum performance from readily available powerplants.

Honda (Mid-1980s): The partnership with Honda in the mid-1980s proved immensely successful, bringing immense power and leading to back-to-back Constructors’ Championships in 1986 and 1987. This period highlighted the critical importance of a strong manufacturer engine partnership in the turbo era, where engine development was a primary battleground.

Renault (1990s): The collaboration with Renault stands as Williams’ most successful engine partnership. Renault power units propelled Williams to five Constructors’ and four Drivers’ titles in the 1990s. This long-term, synergistic relationship between chassis and engine manufacturers was the cornerstone of Williams’ golden age, showcasing the profound impact of a unified technical vision.

BMW (2000s): In the early 2000s, Williams partnered with BMW, a collaboration that brought race wins but ultimately no championships. This period illustrated the changing landscape of F1, where even with a strong manufacturer partner, success was not guaranteed as the sport shifted towards manufacturer-backed “works” teams.

Mercedes (Current): Since the end of 2013, Williams has been a Mercedes engine customer. This partnership has provided a reliable power unit, but the team has largely struggled to escape the midfield in recent years.

Technology Transfer: F1 for the Real World

Williams Racing has consistently demonstrated its commitment to transferring cutting-edge Formula 1 technology and methodologies to broader commercial and societal applications, primarily through its divisions like Williams Advanced Engineering (WAE) and Williams Hybrid Power (WHP). This initiative underscores that Formula 1 is not merely a high-speed spectacle but a vital testbed for real-world innovation.

Supermarket Refrigeration: A notable example of this technology transfer is Williams’ repurposing of its aerodynamics expertise to enhance energy efficiency in supermarket refrigeration. Collaborating with Aerofoil Energy, Williams designed an aluminum device, reminiscent of an F1 car’s rear wing, that prevents cold air from escaping open supermarket fridges. This innovation has been adopted by major UK retailers, including Sainsbury’s, M&S, Tesco, and Asda, with Sainsbury’s alone reporting annual carbon savings of 8,763 tonnes.

London Buses (Regenerative Braking): Williams’ development of a flywheel-based Kinetic Energy Recovery System (KERS) for Formula 1, though not ultimately used in their own F1 cars due to packaging constraints, found a powerful application in public transport. The technology was sold to companies operating London’s iconic red buses, leading to the widespread implementation of regenerative braking systems across UK public transport. This has significantly contributed to reduced carbon emissions, improved fuel efficiency, and lower air pollution in urban environments.

Paediatric Surgery: Perhaps one of the most unexpected yet impactful transfers of F1 methodology occurred in paediatric surgery. In 2001, medical professionals at Great Ormond Street Hospital observed the striking similarities between the efficiency of an F1 pit stop and the critical process of transferring an infant after heart surgery. This realization sparked a unique collaboration with F1 teams, including McLaren and Ferrari, who imparted their knowledge on operational efficiency and clearly defined roles. By applying lessons from the highly synchronized pit stop, where each team member has a specific, critical task, the hospital saw a remarkable 42% reduction in technical errors during these crucial transfers. While not directly a Williams initiative, this exemplifies the broader culture of precision, efficiency, and continuous improvement that Williams, as a leading F1 team, embodies and contributes to the wider world.

Evolution and Challenges: Navigating the New Millennium

Williams Racing entered the 2000s with a formidable legacy, but the Formula 1 landscape was undergoing a significant transformation. The era of the plucky privateer was fading, replaced by a “battle of deep pockets” among automotive giants who increasingly ran their own “works” teams. This marked a profound shift from the independent model that had defined Williams’ earlier triumphs.

The team partnered with BMW from 2000 to 2005, a collaboration that brought renewed competitiveness and a string of race wins, particularly with drivers Ralf Schumacher and Juan Pablo Montoya. Williams, Ferrari, and McLaren consistently locked out the top three Constructors’ positions between 2000 and 2003, with Williams securing two Constructors’ vice-champion slots in 2002 and 2003. However, despite these victories, the team found it challenging to mount a sustained championship challenge against the dominant Ferrari team led by Michael Schumacher. The decision by BMW to depart Williams for another team for the 2006 season was a major blow, forcing Williams to return to Cosworth power for a year before partnering with Toyota. This period starkly highlighted the vulnerability of independent teams reliant on manufacturer engine supply in an increasingly competitive and financially driven sport.

The mid-to-late 2000s saw Williams struggle to maintain its competitive edge. The 2006 season was particularly disappointing, with 20 retirements and a drop to eighth in the Constructors’ standings. While there were flashes of speed, such as Nico Rosberg’s podiums in Australia and Singapore in 2008, these were not indicative of consistent championship pace. Despite developing an innovative double diffuser for the FW31 in 2009, the team failed to capitalize fully and finished seventh in the Constructors’ Championship, reflecting the tightening midfield competition.

The 2010s: A Decade of Decline and Digital Debt

The struggles continued and intensified into the 2010s, culminating in the 2011 season being recorded as their “worst season in team’s history,” yielding a mere five points and only three Q3 appearances. A brief resurgence in 2012, fueled by a return to Renault power, saw Pastor Maldonado secure Williams’ first win since 2004 at the Spanish Grand Prix. Nico Hülkenberg also delivered a surprise pole position in Brazil in 2010, the team’s first since 2005. However, these moments of brilliance were inconsistent, and the team largely remained in the midfield or at the back of the grid.

A critical, yet surprising, underlying cause of Williams’ prolonged decline was its reliance on “outdated technology” and a significant “overdependence on Excel spreadsheets” for managing core operations. In an era where top Formula 1 teams utilized cutting-edge software for logistics, supply chain management, and component tracking, Williams was still using spreadsheets to manage over 20,000 car components and coordinate a 700-person team. This operational inefficiency became a severe bottleneck, creating delays in component tracking, a lack of seamless communication, and ultimately hindering car performance on race day. This technological debt, despite the team employing some of the “greatest engineering minds” in motorsport, severely hampered their competitiveness. The team’s current principal, James Vowles, later attributed the team’s predicament to being “short-termist all the way through the last 20 years,” a period marked by insufficient investment in modern systems. This historical lack of long-term digital transformation and investment created a compounding disadvantage that manifested in tangible on-track performance issues, such as starting the 2024 season with an overweight car due to “archaic planning systems”.

Transition of Ownership: The End of an Era

The mounting financial pressures, exacerbated by poor performance in 2019 and the termination of the ROKiT title sponsorship, led Williams to announce in May 2020 that it was seeking buyers for a portion of the team. Claire Williams, then Deputy Team Principal, openly stated that the COVID-19 pandemic had exposed Formula 1’s “unsustainable model” for smaller, private teams, which disproportionately favored larger, manufacturer-backed operations.

A new chapter for Williams Racing began on August 21, 2020, when the team was acquired by Dorilton Capital, a US-based investment firm. The deal, which reportedly valued the team at €152 million, brought a successful conclusion to the strategic review launched earlier that year. This acquisition marked the profound end of the Williams family’s direct involvement in the team’s operations. Sir Frank and Claire Williams officially stepped down from their roles as Manager and Deputy Manager on September 6, 2020, with the 2020 Italian Grand Prix being their last in those capacities. This was a poignant moment, closing a chapter on one of Formula 1’s most iconic family-run teams.

Dorilton Capital’s stated intent was clear: to adopt a “long-term approach to investment” focused on “restoring the competitiveness of the team” and capitalizing on the sweeping new Formula 1 regulations. This acquisition signaled a new era, promising substantial, strategic investment to overcome the team’s long-standing challenges and return to its former glory.

Current Leadership and Structure

Under its new ownership, Williams Racing has embarked on a comprehensive rebuilding phase. The team is currently owned by Dorilton Capital. James Vowles serves as the Team Principal, having joined ahead of the 2023 season from Mercedes, where he held the position of Motorsport Strategy Director. Vowles is only the third Team Principal in Williams’ 48-year history, a testament to the stability of leadership the team once enjoyed. Pat Fry holds the crucial role of Chief Technical Officer.

For the 2025 Formula 1 season, Williams Racing’s driver lineup will consist of Alex Albon and the highly regarded Carlos Sainz Jr.. The signing of Sainz is considered a significant coup for the team, signaling its growing ambition and attractiveness. The team continues its partnership with Mercedes-AMG as its engine supplier. Beyond the core Formula 1 team, Williams Racing encompasses several key entities, including Williams Heritage, Williams Grand Prix Technologies, the Williams Driver Academy, and the Williams Experience Centre, reflecting a broader engagement with motorsport and technology.

Vision for the Future: The Road Back to Competitiveness

Dorilton Capital’s overarching vision for Williams Racing is ambitious: to “win multiple F1 championships” and return to the very front of the grid. This represents a significant shift from the previous objective of merely ensuring survival. James Vowles has articulated a clear strategic approach to achieve this, emphasizing a “long-term project” focused on “fixing the foundations” of the team. This involves making “strategic sacrifices” in the short term for greater competitiveness in the coming seasons, particularly in anticipation of the major regulation changes slated for 2026. The philosophy dictates prioritizing decisions that yield significant long-term gains over immediate, minor improvements.

The substantial investment from Dorilton Capital has been crucial in this rebuilding process. Over £42.5 million was initially injected to clear existing debts, with further funds allocated for working capital. This capital is being strategically deployed to refurbish and replace factory infrastructure, directly addressing the team’s historical “archaic planning systems” and technological debt. A key aspect of this transformation is a renewed focus on digital transformation, including a partnership with software firm Atlassian, aimed at replacing outdated systems and enhancing communication, workflow efficiency, and decision-making across the organization. The team is actively scaling its simulation capabilities from “tens to thousands per day” and deploying advanced AI tools to accelerate development.

A significant portion of the team’s current efforts is dedicated to the development of the 2026 car, with considerable simulator and wind tunnel time allocated to it. This strategic focus acknowledges the immense opportunity presented by the simultaneous overhaul of both car design and engine regulations in 2026, a scenario not seen in over a decade. Early signs of progress are encouraging; the team has shown improved performance, with Vowles noting they are “over-delivering” and currently sitting higher in the Constructors’ standings than before his tenure. The 2025 car, the FW47, is designed to undercut the minimum weight from the outset, providing valuable ballast flexibility for setup optimization.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Williams Racing’s place in Formula 1 history is cemented as one of the sport’s most successful and influential teams. Its journey from a struggling privateer to a dominant force, and now a team in a strategic rebuild, offers a compelling narrative of resilience and adaptation.

The team’s influence on engineering is undeniable. Its pioneering work on ground effect with the FW07, the perfection of active suspension on the FW14B, and Adrian Newey’s transformative contributions to aerodynamic design that set industry-wide templates all underscore Williams’ role in pushing the technological boundaries of the sport. Their innovations frequently challenged and ultimately shaped the sport’s technical regulations.

In terms of motorsport management, the enduring partnership of Sir Frank Williams and Sir Patrick Head serves as a powerful model of complementary leadership. Frank’s indomitable spirit, fierce independence, and unwavering determination defined the team for decades, even as the sport’s financial landscape evolved beyond the traditional privateer model. His personal battles and triumphs became intrinsically linked to the team’s identity, creating a unique and passionate following.

Williams Racing has also made an indelible contribution to British racing heritage. It provided a platform for legendary British drivers like Nigel Mansell and Damon Hill to achieve their World Championship dreams. The iconic “Red 5” and the fervent “Mansell Mania” remain vivid memories in the annals of British motorsport, symbolizing a golden era of national pride and on-track success.

Ultimately, Williams Racing represents not just a collection of championships and victories, but an enduring spirit of determination, innovation, and a relentless pursuit of excellence. Its story is a testament to the power of human will in the face of adversity and the constant evolution required to thrive at the pinnacle of global sport. This rich legacy continues to inspire, as the team embarks on a new chapter, driven by the ambition to return to its rightful place at the front of the grid.

Some genuinely good information, Glad I found this.