Formula 1 is often described as a sport, but at its granular, molecular level, it is a high-speed litigation of physics. The Technical Regulations, published annually by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), do not serve merely as a rulebook; they are a set of constraints defining a solution space. For the engineers at Brixworth, Maranello, Viry-Châtillon, and Sakura, the objective is not simply to comply with these regulations but to exploit the undefined spaces between them—the “grey zones.”

The era spanning from 2014 to 2025, known as the Turbo-Hybrid era, represents the most complex engineering challenge in the history of automotive competition. The transition from 2.4-liter naturally aspirated V8s to 1.6-liter V6 turbo-hybrids was not merely a change in displacement; it was a fundamental shift in the currency of performance. Where previous eras chased volumetric efficiency and maximum RPM, the hybrid era chased thermal efficiency and energy management.1 The restriction of fuel flow to 100kg/hour turned the internal combustion engine (ICE) into a chemistry experiment, forcing teams to extract every joule of energy from a finite chemical allowance.

This report investigates the technical warfare of this era, focusing on the two distinct dynasties that defined it: the architectural hegemony of Mercedes-AMG High Performance Powertrains (HPP) and the metallurgical renaissance of Honda. Through the lens of patent-worthy innovations, controversial fluid dynamics, and aerospace collaborations, we reveal how the limits of legality were pushed, how sensors were tricked by resonance, and how the alchemy of “Kumamoto plating” and “party modes” decided the fate of World Championships.

The paradigm shift in Formula 1 propulsion philosophy:

Era Characteristic | V8 Era (2006–2013) | V6 Turbo-Hybrid Era (2014–2025) |

Primary Objective | Airflow Maximization (Volumetric Efficiency) | Fuel Energy Conversion (Thermal Efficiency) |

Fuel Limit | Unrestricted (approx. 160kg/race) | 100kg/h flow rate; 110kg/race mass |

Hybrid Power | KERS (60kW / 6.7s per lap) | ERS (120kW MGU-K + Unlimited MGU-H) |

Thermal Efficiency | ~29% | >52% |

Dominant Philosophy | RPM & Acoustical Tuning | Thermodynamics & Energy Deployment |

The Silver Arrow Doctrine: Architecture as Destiny

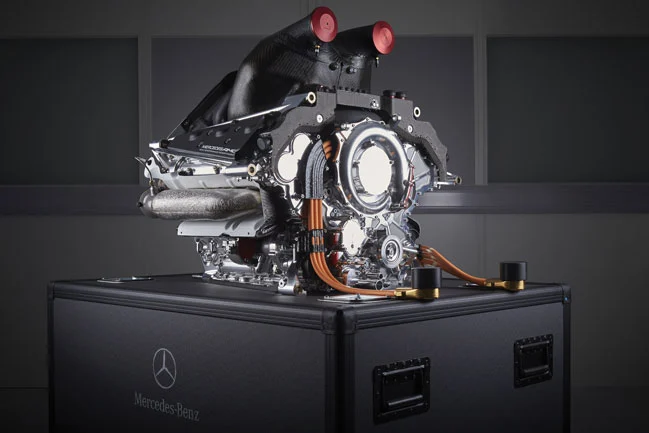

When the 2014 regulations were ratified, the vast majority of the paddock viewed the powertrain as a sum of bolt-on components: an engine, a turbocharger, and two electric motors. Mercedes-AMG HPP, under the technical stewardship of Andy Cowell, viewed it as a singular, integrated organism. Their dominance for seven consecutive seasons was rooted in a single, pivotal architectural decision made years before the lights went out in Melbourne: the split turbocharger.

In a conventional turbocharger layout, used by Renault and Ferrari in 2014, the turbine (driven by exhaust gas) and the compressor (driven by the turbine to pressurize intake air) are housed in a single unit, typically mounted at the rear of the engine block. This proximity creates a significant thermal management problem: the turbine operates at temperatures exceeding 900°C, while the compressor requires cool, dense air to maximize combustion efficiency. Heat soak from the turbine to the compressor heats the intake charge, reducing air density and increasing the likelihood of detonation (knock).

Mercedes devised the PU106A architecture to solve this thermodynamic conflict physically. They separated the compressor and the turbine, mounting the compressor at the front of the engine block and the turbine at the rear. The two components were connected by a long shaft running through the V-bank of the internal combustion engine.

Thermal Isolation and Intercooling

The primary advantage of this layout was thermal isolation. By placing the compressor in the “cold zone” at the front of the engine, away from the searing heat of the exhaust manifold and turbine, Mercedes ensured a naturally cooler intake charge. In thermodynamics, cooler air is denser, containing more oxygen molecules per unit volume. This allowed Mercedes to run significantly smaller intercoolers than their rivals. While Ferrari and Renault cars required large, drag-inducing sidepod radiators to cool the superheated air from their conventional turbos, the Mercedes W05 could utilize compact cooling solutions, creating a virtuous cycle of aerodynamic efficiency.

The Aerodynamic Ripple Effect

The implications of the split turbo extended far beyond the engine bay. The conventional turbo layout places a bulky housing at the rear of the engine, forcing the gearbox to be moved backward and compromising the “coke bottle” area—the crucial narrowing of the bodywork at the rear of the car that feeds airflow to the diffuser.

By moving the compressor to the front, Mercedes removed a significant volume of hardware from the rear of the chassis. This allowed the gearbox to be mounted further forward, shortening the effective wheelbase for packaging or allowing for a more tapered rear bodywork design. This architectural advantage meant that the Mercedes power unit was not just a horsepower generator; it was an active component of the car’s aerodynamic concept, enabling a level of rear-end downforce that rivals could not mechanically replicate.

MGU-H Placement and Shaft Dynamics

The challenge of the split turbo was the shaft. A steel shaft running the length of the engine block at 100,000 RPM is subject to immense torsional vibration and harmonic resonance. To mitigate this, Mercedes placed the Motor Generator Unit-Heat (MGU-H) directly in the center of the V-bank, coupled to the shaft. This positioning protected the MGU-H from crash damage and heat, but more importantly, the electrical machine acted as a damper for the shaft’s vibrations. This allowed for precise control over turbo speed, virtually eliminating turbo lag. When the driver applied the throttle, the MGU-H would spin the compressor instantly before exhaust pressure built up, delivering the immediate torque response of a naturally aspirated engine.

The Pursuit of 50% Thermal Efficiency

The target set by the FIA for the hybrid era was a thermal efficiency of 40%. For context, the previous generation of V8 engines achieved roughly 29% efficiency, wasting over 70% of the fuel’s energy as heat and sound. Mercedes arrived at the first test in 2014 already achieving 44% efficiency. By 2017, they had surpassed 50% on the dyno at Brixworth, a milestone unprecedented in gasoline automotive history.

Fluid Dynamics as a Weapon: The Oil Burning Saga

As the architectural advantages of the split turbo became understood and copied, the battleground shifted to the chemistry of combustion. Between 2015 and 2017, a controversial practice emerged that would define the mid-hybrid era: oil burning.

The Chemistry of Auxiliary Fuel

The FIA regulations strictly policed the flow of petrol. However, the consumption of engine oil was regulated primarily by environmental and reliability concerns, not performance limits. Engineers at Mercedes (and subsequently Ferrari) realized that modern synthetic engine oils are composed of long-chain hydrocarbons, not dissimilar to fuel. If this oil could be introduced into the combustion chamber, it would contribute to the energy release.

The benefits of burning oil were twofold:

- Energy Density: High-performance synthetic oils have a high calorific value, effectively bypassing the 100kg/h fuel flow limit by adding “unmetered” energy to the cylinder.

- Knock Suppression: By collaborating with petrochemical partners like Petronas, teams formulated oils rich in additives that improved the octane rating of the mixture. When introduced into the combustion chamber, these oils acted as anti-knock agents, allowing the engine to run more aggressive ignition timing and leaner fuel mixtures without detonating.

Mechanisms of Introduction

The methods for introducing oil into the combustion chamber were ingenious and varied.

- PCV Manipulation: The Crankcase Ventilation System, designed to recirculate blow-by gases, was tuned to separate oil vapor and feed it directly into the intake plenum.

- Valve Guide Permeability: Tolerances on valve stems and seals were loosened to allow a controlled seepage of oil from the cylinder head into the intake ports.

- Active Injection: There were persistent suspicions of “auxiliary oil tanks” ostensibly designed for replenishing the sump, being used to inject specific, high-volatility “qualifying oils” into the induction system on demand.

The 2017 Crackdown and the "Spa Loophole"

By 2017, the FIA recognized that oil burning had become a primary performance differentiator, particularly in qualifying. To curtail this, they issued a Technical Directive reducing the allowable oil consumption from an unlimited/generous tolerance to a strict 0.9 liters per 100km, effective from the Italian Grand Prix (Monza) onwards.

This regulation created a critical tactical juncture. The rule stated that the new 0.9L/100km limit would apply to any new engine specification introduced from Monza onwards. Engines introduced before that date would be grandfathered under the previous, more lenient 1.2L/100km limit.

Mercedes executed a masterstroke of logistical planning. They fast-tracked the introduction of their final Power Unit specification (Spec 4) for the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps—exactly one race before Monza. By introducing the engine at Spa, Mercedes locked in the 1.2L/100km limit for the remainder of the season for Lewis Hamilton and Valtteri Bottas. Ferrari, unable to ready their update in time, introduced their new engine at Monza, forcing them to adhere to the stricter 0.9L/100km limit.

This maneuver allowed Mercedes to burn 33% more oil than their rivals for the final seven races of the championship, a significant advantage in qualifying trim where every milligram of combustible material counted.

"Party Mode" and Technical Directive 37

The culmination of oil burning and aggressive mapping was the so-called “Party Mode” (Strat 2 in Mercedes nomenclature). Used primarily in Q3 and race restarts, this mode maximized boost pressure, RPM, and permitted maximum oil consumption to deliver a short-term power spike, estimated to be worth up to 0.3 seconds per lap.

In 2020, the FIA finally slammed the door on this practice with Technical Directive 37 (TD37). The directive mandated that teams must run the same engine mode in qualifying and the race. The intention was to ban Party Modes and hamper Mercedes’ qualifying dominance.v

However, the result was counter-intuitive. Because Mercedes no longer had to reserve engine life for the extreme stress of Party Mode in qualifying, they could afford to run a higher average power mode throughout the entire race distance. As Toto Wolff predicted, the ban effectively improved Mercedes’ race pace, as the engine life saved on Saturday was deployed on Sunday.

The Ghost in the Machine: Sensor Aliasing and Fuel Flow

While oil burning was a chemical loophole, the most sophisticated controversy of the era was electronic: the manipulation of the fuel flow meter (FFM) via signal aliasing.

The Ultrasonic Blind Spot

The FIA-mandated fuel flow meter, manufactured by Gill Sensors, utilized ultrasonic time-of-flight technology to measure fluid velocity. Crucially, the sensor did not measure flow continuously in an analog fashion; it sampled the flow rate at a specific frequency, approximately 2.2 kHz.

This digital sampling rate created a vulnerability known as aliasing. In signal processing, if a variation occurs at a frequency higher than the Nyquist rate (half the sampling rate), the sensor cannot accurately reconstruct the signal. Engineers realized that if they could synchronize the fuel pump pulses to occur in the “blind spots” between the sensor’s sampling intervals, they could inject extra fuel without the sensor detecting a breach of the 100kg/h limit.

The Resonance Trick

The method involved creating a harmonic resonance in the fuel line. By tuning the high-pressure fuel pump to pulsate at a frequency that was perfectly out of phase with the sensor’s sampling cycle, teams could theoretically push a burst of fuel through the meter between samples A and B.

- Scenario:

- Sample A (0.000s): Flow reads 99.9 kg/h (Legal).

- Interval (0.0002s): Pump pulses flow to 110 kg/h (Illegal, but unmeasured).

- Sample B (0.00045s): Flow reads 99.9 kg/h (Legal).

This technique allowed teams to exceed the flow limit by small but cumulative margins, providing more chemical energy for combustion.

The Sentronics Solution and Encryption

The FIA responded to growing suspicions—most notably surrounding Ferrari’s rapid straight-line speed gains in 2019—by introducing a secondary, encrypted fuel flow meter manufactured by Sentronics.

The Sentronics meter featured “anti-aliasing” technology. It utilized randomized sampling intervals, making it impossible for team software to predict when the measurement would be taken. Furthermore, the data from this sensor was encrypted and accessible only to the FIA, preventing teams from using the sensor data in a feedback loop to tune their pumps.

The introduction of this dual-sensor system in late 2019 coincided with a marked decrease in straight-line performance for certain teams, effectively closing the loop on electronic flow manipulation.

The Samurai’s Renaissance: Honda’s Return from the Abyss

While Mercedes was refining its dominance, Honda was living a public nightmare. Their return to Formula 1 in 2015 with McLaren was characterized by the “Size Zero” concept—an attempt to package the engine even more aggressively than Mercedes. The result was a catastrophe: the turbocharger was too small to generate sufficient boost, and the MGU-H could not harvest enough energy, leading to “clipping” (running out of electrical power) halfway down straights.

However, the trajectory from the “GP2 Engine” insults of 2015 to the World Championship in 2021 is one of the greatest engineering turnarounds in motorsport history. It was driven by a radical change in leadership and the integration of Honda’s aerospace and motorcycle divisions.

The "New Framework": RA621H

The turning point came under the leadership of Yasuaki Asaki, the Head of HRD Sakura. Known as a “maverick” within Honda’s conservative corporate culture, Asaki pushed for a complete redesign of the power unit for 2021, despite the company’s decision to leave the sport at the end of that year.

The 2021 engine, designated RA621H, was originally scheduled for 2022. Asaki convinced CEO Takahiro Hachigo to fast-track its development, compressing a two-year R&D cycle into six months. The “New Framework” architecture featured several radical changes:

- Compact Camshaft Layout: The camshafts were lowered and moved closer together. This reduced the overall height of the cylinder head, lowering the engine’s center of gravity.

- Bore Pitch Reduction: Honda reduced the distance between cylinder centers (bore pitch), making the V6 block significantly shorter. This allowed Red Bull to package the rear of the RB16B even tighter than before, enhancing airflow to the floor.

- Bank Offset Reversal: The cylinder bank offset was reversed (right bank forward, left bank back) to align better with the chassis structural loads.

Material Alchemy: Kumamoto Plating

To extract more power from the smaller RA621H, Honda needed to increase combustion pressure and temperature. The limiting factor was the durability of the cylinder walls. To solve this, Honda turned to its motorcycle division at the Kumamoto factory.

They adapted a proprietary cylinder sleeve plating technology known as “Kumamoto Plating.” This advanced surface treatment significantly reduced the coefficient of friction between the piston rings and the cylinder liner.

- Thermal Conductivity: The plating had superior thermal transfer properties, allowing heat to dissipate from the combustion chamber into the water jacket more efficiently. This prevented “hot spots” that lead to knocking.

- Rapid Combustion: With better heat management, Honda could implement “Rapid Combustion” geometry, running higher compression ratios and more aggressive ignition timing without risking engine failure.

- Reliability: The reduced friction meant less wear, allowing the engine to maintain peak performance for longer durations. While rival engines lost horsepower as they aged due to degradation, the RA621H maintained its “fresh” performance curve deep into its lifecycle.

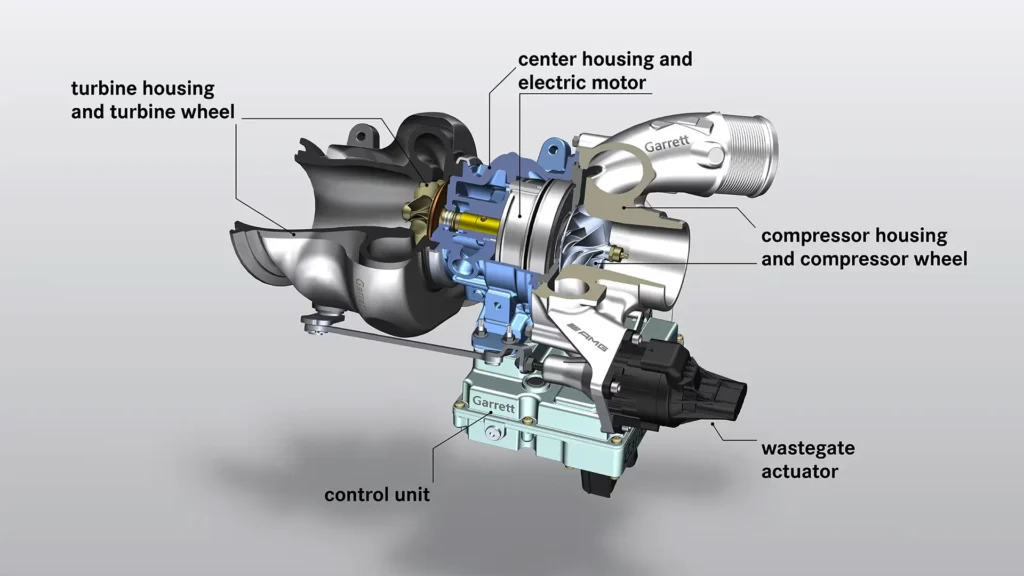

Aerospace Integration: The IHI Turbocharger

The failures of the “Size Zero” era were largely due to turbo inefficiency. To rectify this, Honda established a deep technical collaboration with IHI Corporation, the manufacturer of the turbochargers, and the HondaJet aerospace division.

The collaboration brought genuine jet engine technology to the F1 power unit:

- Single-Crystal Superalloys: The turbine blades were manufactured using single-crystal nickel-based superalloys, similar to those used in high-bypass turbofan jet engines. These materials have no grain boundaries, providing exceptional resistance to creep (deformation) at high centrifugal loads and temperatures exceeding 1000°C.

- Airfoil Optimization: HondaJet engineers redesigned the aerodynamic profile of the compressor and turbine blades using aerospace computational fluid dynamics (CFD). This allowed the turbo to spin up faster (reducing lag) and operate efficiently at a wider range of mass flow rates.

- Shaft Dynamics: The vibration issues that plagued the long shaft in 2015-2017 were solved using shaft balancing techniques derived from the HF120 jet engine program.

This collaboration transformed the Honda turbo from a liability into a weapon. By 2021, the Honda MGU-H harvesting was so efficient that it could effectively run in a “self-sustaining” mode, feeding energy directly to the MGU-K without draining the battery.

Energy Warfare: The Strategy of Clipping

The physical battles of 2021 were visible on track, but the strategic war was fought in the Energy Management System (EMS). Red Bull and Honda adopted a counter-intuitive strategy known as “clipping” to manage their energy deployment against Mercedes.

The Mechanics of Clipping

“Clipping” occurs when the EMS cuts the electrical power delivery to the MGU-K before the car reaches the end of a straight. To the observer (and the driver), this feels like the car hits a “wall” of resistance, as the 160 horsepower of electrical assist vanishes, leaving only the internal combustion engine to push the car against aerodynamic drag.

While clipping hurts top speed, Red Bull utilized it as a strategic tool. By cutting deployment early on the straights, the system saves battery charge (State of Charge – SoC). This ensures that the Energy Store is never fully depleted.

- The Tactical Advantage: By clipping at the end of the straight, Red Bull ensured they had 100% electrical torque available for the next acceleration event. In F1, lap time is gained primarily in the traction zones (exiting corners), not at terminal velocity. The Honda strategy prioritized having a full battery for every corner exit, giving Max Verstappen superior punch out of slow corners compared to Mercedes, who often ran a more sustained deployment profile.

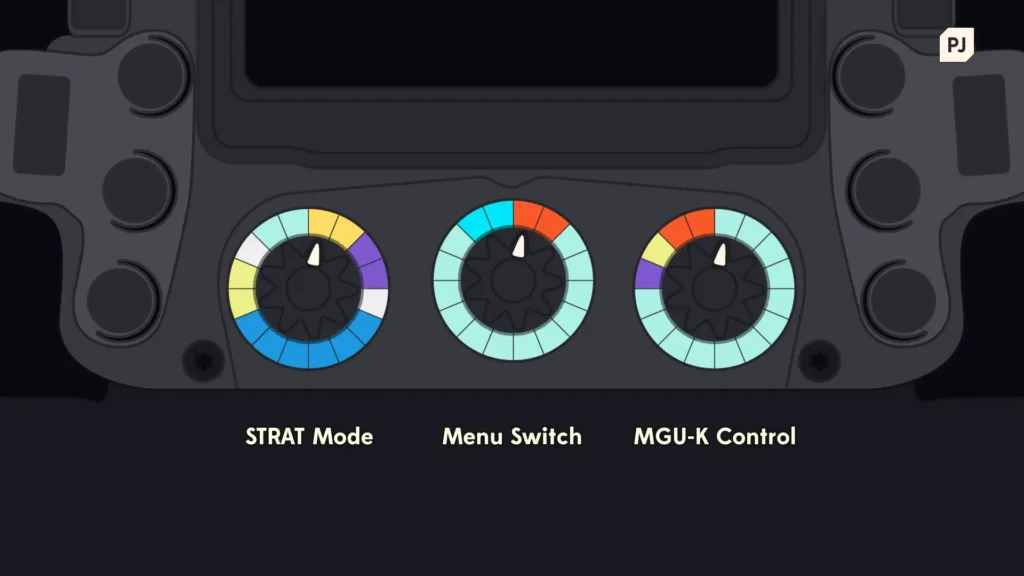

Strat Modes and Deployment Profiles

The steering wheel of the Red Bull featured various “Strat” (Strategy) modes that controlled this behavior.

- Strat 2: Typically a qualifying or “attack” mode. This minimizes clipping, deploying energy all the way to the braking zone for maximum lap time, at the expense of draining the battery.

- Strat 11: A race-sustainable mode. This introduces calculated clipping to keep the battery level neutral (harvesting = deployment) over the course of a lap, preventing the driver from ever finding themselves with a “dead” battery during a battle.

The efficiency of the IHI/Honda MGU-H was critical here. Because the MGU-H can harvest unlimited energy (unlike the MGU-K, capped at 2MJ/lap), the Honda PU could harvest aggressively on the straights (via exhaust gas) and feed that power directly to the MGU-K, bypassing the battery entirely. This “direct drive” loop allowed Red Bull to maintain high deployment levels even while managing the battery SoC.

The Legacy of the RA621H and the Red Bull Dynasty

The 2021 season concluded with Max Verstappen’s championship, a victory built on the foundation of the RA621H. However, the story did not end with Honda’s official withdrawal. The intellectual property of this engine became the cornerstone of Red Bull Powertrains (RBPT).

The “New Framework” engine proved to be exceptionally adaptable to the 2022 ground-effect regulations. Its compact size allowed Adrian Newey to design the RB18 and RB19 with cavernous underfloor tunnels, maximizing the ground effect downforce. The reliability of the Kumamoto-plated block allowed Red Bull to focus development on aerodynamics rather than engine firefighting. The engine, rebadged but fundamentally Honda, powered Red Bull to the most dominant seasons in F1 history in 2022 and 2023.

Technical comparison of the 2021 Championship contenders.

Feature | Mercedes-AMG F1 M12 | Honda RA621H |

Architecture | Split Turbo (Established 2014) | Split Turbo (New Compact Framework) |

Combustion Tech | Pre-Chamber Ignition (TJI) | High-Speed Combustion + Kumamoto Plating |

Turbo Tech | In-House / BorgWarner | IHI / HondaJet Aerospace Alloys |

Center of Gravity | Low | Ultra-Low (Compact Camshafts) |

Philosophy | Peak Power & Efficiency | Packaging & Drivability |

2026 and Beyond: The Next Battleground

As the sport moves toward the 2026 regulatory overhaul, the lessons of the turbo-hybrid era have shaped the future rulebook. The FIA has moved to close the very loopholes that defined the last decade, while opening new ones.

The Death of the MGU-H

The defining technology of the era, the MGU-H, will be banned in 2026. The FIA deemed it too complex, expensive, and irrelevant to road cars. This removal fundamentally changes the energy equation.

- Turbo Lag Return: Without the MGU-H to spin the turbo electrically, traditional turbo lag becomes a threat.

- Torque Fill: The MGU-K power will nearly triple to 350kW (approx. 470hp). It will be tasked with “torque filling”—masking the turbo lag by deploying massive electrical torque instantly while the turbo spools up.

- 8.2 Active Aero and “Manual Override”

To compensate for the loss of MGU-H harvesting, the 2026 cars will feature Active Aerodynamics. Wings will flatten on straights to drastically reduce drag, lowering the energy required to maintain top speed. Additionally, a new “Manual Override” mode will replace DRS, allowing a chasing driver to deploy extra electrical power up to 355kph to attempt an overtake.

The New Grey Zones

History teaches us that simplification merely shifts the location of the loopholes. With the 2026 regulations shifting to an energy flow limit (MJ/lap) rather than a mass flow limit, and the introduction of 100% sustainable fuels, the next war will be fought in the chemical synthesis of these fuels and the software algorithms that manage the massive 350kW electrical deployment. The “Unfair Advantage” is dead; long live the Unfair Advantage.

Conclusion

The story of the Formula 1 Turbo-Hybrid era is a testament to the fact that the “spirit of the regulations” is a myth; there is only the text, and what can be engineered in its silence.

Mercedes dominated the first half of the era by reading the text of the 2014 rules and realizing that architecture—the split turbo—was the key to thermal efficiency. They sustained that dominance by exploiting fluid dynamics, turning oil into fuel until the FIA legislated the practice out of existence.

Honda, conversely, proved that even a catastrophic start can be salvaged through cross-disciplinary humility. By treating the F1 engine not just as a car part, but as an aerospace component requiring jet-grade materials and motorcycle-grade coatings, they built a power unit capable of ending the Silver Arrow dynasty.

The legacy of this era is not just the trophies, but the technological spinoffs—from 50% thermal efficiency (now a target for road cars) to the advanced material sciences of Kumamoto and Brixworth. As the sport resets for 2026, the engineers are already searching for the next grey zone, the next resonance frequency, and the next hidden tank that will define the future of speed.