O País do Automobilismo (The Country of Motorsport)

Brazil’s relationship with Formula 1 is unique, defined by an explosive cocktail of dazzling

natural talent, deep-seated national passion, and monumental tragedy. For millions of

Brazilians, the sight of the green, yellow, and blue flag cresting a podium finish transcends

mere sporting achievement; it is a source of intense national pride, especially during periods

of economic or political turbulence. Motorsport is not just a recreational pursuit in Brazil; it is a

cultural cornerstone.

This profound connection has fueled a remarkable dynasty in the sport. Since the first

tentative steps in 1951, Brazil has exported a staggering amount of world-class talent,

contributing 33 drivers to the Formula 1 World Championship grid. This collective effort has

resulted in a haul of 101 Grand Prix victories and 293 podium finishes, metrics that solidify

Brazil’s standing as one of the sport’s perennial powerhouses.

At the apex of this history sit three titans—the World Champions who etched Brazil’s name

into the F1 record books: Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson Piquet, and Ayrton Senna. Together, they

secured the coveted World Drivers’ Championship title eight times (1972, 1974, 1981, 1983,

1987, 1988, 1990, 1991). Their dominance created a golden age that established a benchmark

for excellence that succeeding generations have constantly striven to meet.

Furthermore, the spiritual home of automobilismo in Brazil, the Autódromo José Carlos Pace, better known as Interlagos, stands as one of the most iconic circuits on the calendar. Known for its challenging, old-school layout, dramatic elevation changes, and the intense, carnival-like atmosphere provided by the vibrant city of São Paulo, Interlagos continues to be the stage where Brazil’s motor racing history is simultaneously celebrated and written.

This history is not linear; it is a story of five distinct eras, each one building on the legacy of

the last. The early pioneers fought simply to enter the field, establishing the foundational

aspiration. Their efforts were repaid by the champions of the 1970s and 1980s, who formalized

Brazil’s presence. The subsequent generations, defined by the endurance of Rubens

Barrichello and the heartbreak of Felipe Massa, kept the flag flying during periods of

transition. This comprehensive exploration charts the course of every Brazilian Formula 1

driver, documenting their careers, achievements, and the indelible mark they left on the

fastest sport in the world, tracing the Brazilian F1 history from its humble beginnings to the

current promise of new talent.

Era I: The Pioneers – Laying the Foundation (1950s–1960s)

The first two decades of the Formula 1 World Championship era were characterized by limited

budgets, nascent technology, and the massive logistical challenge for non-European drivers

to participate. For Brazilians, securing a drive meant overcoming immense financial hurdles,

resulting in sparse, privateer-led entries. These foundational drivers, however, were crucial in

establishing the initial link between Brazil and the global stage of motor racing.

Francisco ‘Chico’ Landi (Debut 1951): The Undisputed Master

The journey began with Francisco Sacco Landi, better known as Chico Landi, who holds the

distinction of being the first Brazilian ever to participate in a Formula 1 Grand Prix. Landi

made his debut at the 1951 German Grand Prix, driving for a privateer entry.

Landi’s career, active between 1951 and 1956, was typical of the era, involving multiple

privateer teams and driving machinery from manufacturers like Maserati and Ferrari. His initial

ambition was driven by a genuine passion, having already been the undisputed master of

pre-war racing in Brazil, where he helped popularize the sport. Unlike other early competitors

from wealthy backgrounds, Landi hailed from a modest middle-class family, enhancing his

status as the most popular Brazilian driver of his time.

Landi’s greatest historical achievement was becoming the first Brazilian to score points in

the World Championship. This feat occurred at the 1956 Argentine Grand Prix, where he

finished fourth. Reflecting the resource constraints of early F1, he earned his 1.5 career

points by sharing the drive of the Officine Alfieri Maserati 250F with Gerino Gerini. This

shared drive vividly illustrates the struggle: for a Brazilian talent to score points, it required

pooling resources and drivers—a stark contrast to the massive factory efforts that would

emerge later. Landi thus represents the initial aspiration of Brazilian motorsport, fueled by raw

talent fighting against European dominance in both technology and funding.

The Early Entrants: Gino Bianco, Hermano da Silva Ramos, and Fritz d’Orey

Landi’s precedent paved the way for a handful of other Brazilian drivers in the decade,

although their F1 careers remained fleeting. Landi’s precedent paved the way for a handful of other Brazilian drivers in the decade, although their F1 careers remained fleeting.

Gino Bianco (Debut 1952): Bianco made his F1 entry in 1952, racing for the Escuderia Bandeirantes. He participated in three races, showcasing the Brazilian effort to pool resources to secure entries in the World Championship calendar.

Hermano da Silva Ramos (Debut 1955): Da Silva Ramos participated in seven Grand Prix

entries across 1955 and 1956, driving for the French Gordini team. He managed a best finish of eighth place, a respectable result in an era dominated by factory teams like Mercedes and

Ferrari.

Fritz d’Orey (Debut 1959): D’Orey’s brief career included three entries, driving for Tec-Mec

and Scuderia Centro Sud. Like many drivers of his time, his career was curtailed, with injury

playing a role.

These early entrants established the principle of Brazilian participation, even if success remained distant. Their struggle highlights the immense resource gap that needed to be bridged, setting the stage for the systematic, career-defining investment that would characterize the next generation of Brazilian motorsport heroes.

Era II: The Rise of Champions – Establishing Dominance (1970s–1980s)

The 1970s marked a dramatic shift. Brazil transitioned from struggling to secure a single grid

spot to producing drivers who could compete for, and secure, World Championships. This era

was defined by a new wave of ambitious, well-supported talent, most notably the two

champions who set the stage for the golden age: Emerson Fittipaldi and Nelson Piquet.

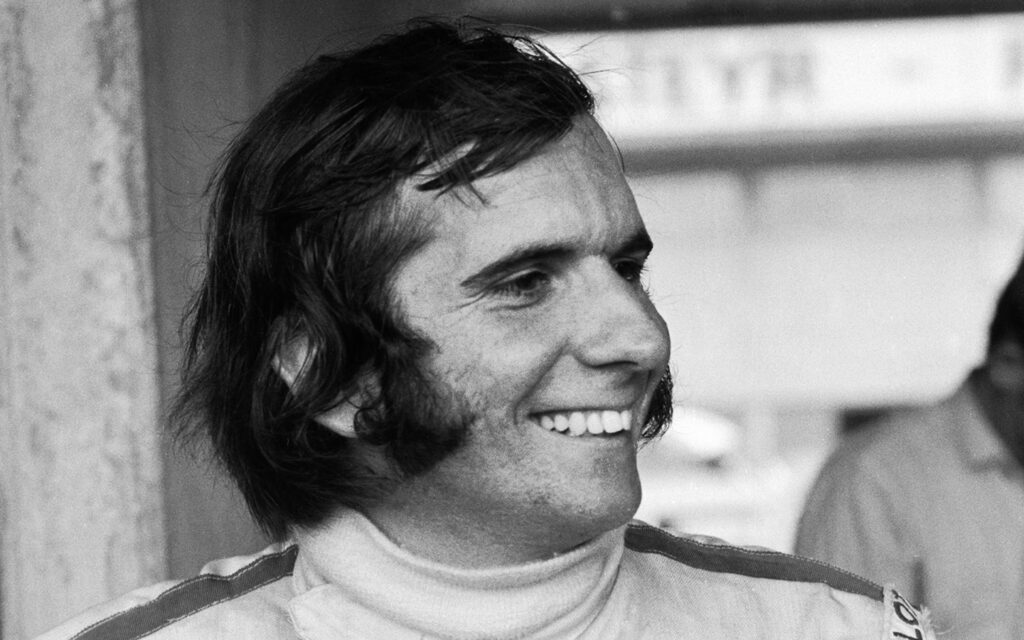

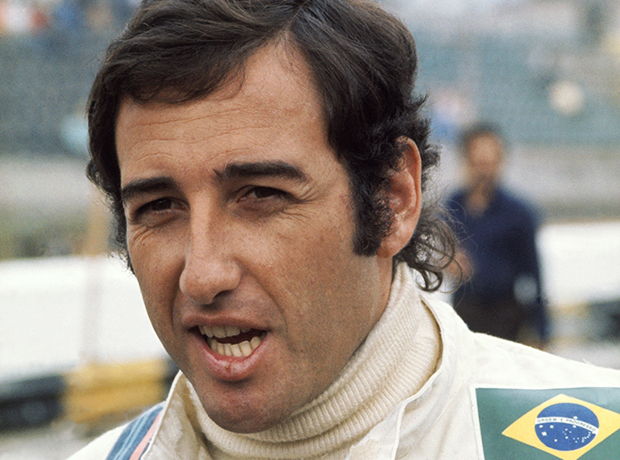

Emerson Fittipaldi (Debut 1970): The Golden Boy and Pioneer Champion

Emerson Fittipaldi’s arrival symbolized the professionalization of Brazilian motor racing. Moving to Europe and rapidly graduating from Formula Two, he made his Formula One debut for Team Lotus at the 1970 British Grand Prix. Fittipaldi possessed a driving style characterized by “amazing anticipation, coordination, and reflex,” enabling him to operate with smooth precision at high speeds.

Fittipaldi was thrust into the spotlight quickly, becoming Lotus’s lead driver in his fifth Grand

Prix after the tragic death of Jochen Rindt. He immediately responded by winning the first

post-Rindt race at the United States Grand Prix.4 His breakout season came swiftly.

The Record-Breaking Champion

In 1972, Fittipaldi secured his first World Drivers’ Championship, becoming, at the age of 25, the youngest F1 world champion at the time, a record that stood for 33 years. This achievement was monumental; it validated Brazil as a supplier of not just competitive drivers, but of true world-beaters. Fittipaldi had legitimized the aspirations begun by Landi two decades earlier.

He went on to clinch his second title in 1974 with McLaren, helping the team secure its first-ever Constructors’ Championship. Fittipaldi’s success across two different teams (Lotus and McLaren) in different regulatory periods demonstrated his adaptability and skill, yielding a total of 14 wins and 35 podiums in his F1 career.

The National Dream: Fittipaldi Automotive

Fittipaldi’s ultimate legacy was not just statistical but nationalistic. Prior to the 1976 season, he “surprised the paddock” by leaving the competitive McLaren team to join Fittipaldi Automotive. This effort, also known as Copersucar, was founded by his brother, Wilson Fittipaldi Júnior, and was intended to be a wholly Brazilian-backed factory effort, using technology and engineering prowess developed by the nation. While the team struggled financially and technically, never achieving the desired success, this ambitious venture was a powerful statement of Brazilian self-determination, proving that the nation aimed not only to produce world-class drivers but also to build world-class machinery.

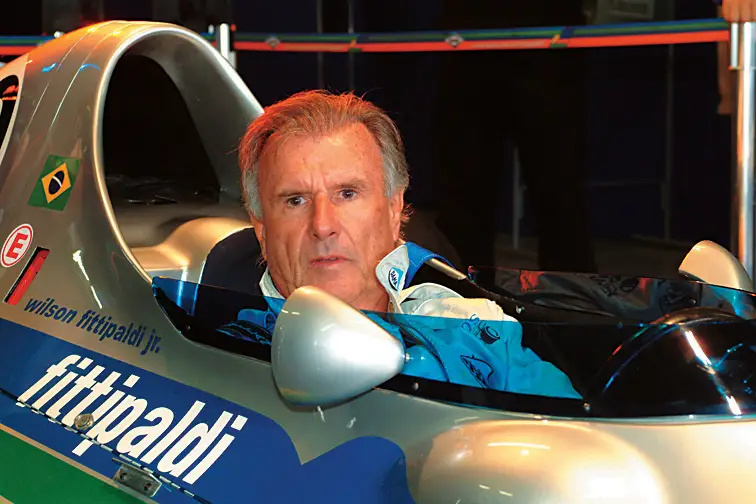

Wilson Fittipaldi Júnior (Debut 1972) and the Engineering Aspiration

Wilson Fittipaldi Júnior, Emerson’s older brother, made his debut in 1972 with Brabham. While his statistics (35 starts, 0 wins) did not match his brother’s, his contribution was instrumental in the business and infrastructure of Brazilian F1. He was the driving force behind the Copersucar project, pouring immense energy into developing the first and only full-fledged Brazilian F1 team. This deep dive into the engineering side further broadened Brazil’s impact, extending the legacy beyond the cockpit and into the factory.

José Carlos Pace (Debut 1972): Interlagos’ Immortal

José Carlos Pace, who debuted in 1972, raced for teams including Surtees and Brabham.

Although his career statistics (72 starts, 1 win, 6 podiums) might appear modest compared to

the champions, his place in Brazilian history is sacred.

Pace achieved his single, defining victory at the 1975 Brazilian Grand Prix. This home win cemented his status as a national hero. Following his tragic death in a private plane crash in 1977, the Interlagos circuit was officially renamed Autódromo José Carlos Pace. This act demonstrates that in Brazilian motorsport, influence is measured not just by WDC trophies, but by individual moments of heroism and the deep emotional connection forged with the fans. The naming of the nation’s premier circuit after Pace ensures his impact is perpetually linked to the track’s “electric atmosphere” and “old-school layout”.

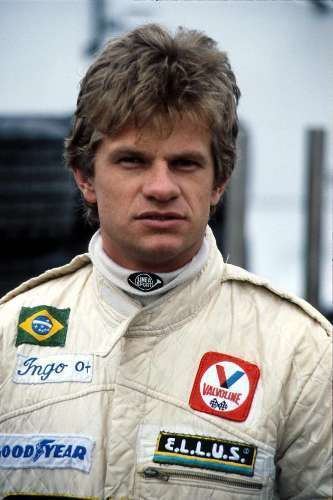

The Mid-70s Bridge: Luiz Bueno, Ingo Hoffmann, and Alex Ribeiro

The success of Fittipaldi inspired other Brazilian drivers to seek F1 berths, proving the talent pipeline was expanding:

Luiz Bueno (Debut 1973): Bueno made a single Grand Prix start at the 1973 Brazilian Grand Prix.

Ingo Hoffmann (Debut 1976): Hoffmann had six F1 entries, often associated with the Fittipaldi team during its attempts to gain stability. He later became a legend in the Brazilian Stock Car scene.

Alex Ribeiro (Debut 1976): Ribeiro had 20 entries over sporadic appearances in 1976, 1977, and 1979, driving for small teams like Hesketh and March. These drivers collectively represented the critical mass of talent pushing for grid spots, a necessary condition for sustained excellence.

Nelson Piquet (Debut 1978): The Pragmatic Strategist

Nelson Piquet Souto Maior entered F1 in 1978 with Ensign, rapidly transitioning to Brabham. Piquet’s trajectory was marked by a calculating, often controversial, ambition. He began his career by prioritizing success over tradition, using his mother’s maiden name, Piquet, to hide his racing endeavors from his disapproving father. This early calculated risk set the tone for a career defined by strategic execution.

Piquet was quickly recognized as a prodigy in European motorsport, setting a record for the most wins in Formula Three in a season upon the advice of Emerson Fittipaldi.

The Three-Time World Champion

Piquet’s career was defined by his mastery of the rapidly evolving technological landscape of the 1980s. He secured three World Drivers’ Championship titles (1981, 1983, 1987), tallying 23 wins and 60 podiums.

Piquet’s driving style contrasted sharply with Fittipaldi’s earlier fluidity and Senna’s later intensity. He was hailed as the pragmatic engineer—a meticulous strategist focused intensely on car setup and race management, particularly crucial during the brutal, high-power turbo era. His second title in 1983, driving the Brabham-BMW, marked the first WDC won with a turbocharged engine, signifying his superior technical adaptability.

Piquet’s final title in 1987 came during his stint at Williams, where he was embroiled in a “heated battle with teammate Nigel Mansell,” a rivalry marked by intense personal animosity. Piquet’s ability to secure the title despite this high-pressure, fractured internal dynamic speaks to his mental resilience. He himself reflected that overcoming difficult periods helped him strengthen himself mentally to achieve subsequent business successes.

The success of Piquet and Fittipaldi proved that Brazil was an F1 powerhouse, capable of

producing champions across different generations and technological specifications. This

paved the way for the ultimate icon of the sport.

Era III: The Golden Age of Senna – Intensity and Iconography (1980s–1990s)

The late 1980s and early 1990s are universally regarded as the zenith of Brazilian involvement

in Formula 1, an era defined almost entirely by one man: Ayrton Senna da Silva.

Ayrton Senna (Debut 1984): The Rain Master and National Hero

Ayrton Senna made his debut with Toleman in 1984, quickly moving to Lotus and then McLaren, where he achieved immortal status. Senna secured three World Drivers’ Championships (1988, 1990, 1991), accumulating 41 wins and 80 podiums in just 161 starts.

Signature Traits and Defining Rivalry

Senna’s signature racing trait was his almost religious commitment to perfection and speed.

He defined the concept of the modern, intense racing athlete. He was famously known as the

Rain Master, capable of finding grip and speed in treacherous wet conditions that paralyzed

his competitors.

His career was inexorably linked to his bitter rivalry with Alain Prost. This decade-spanning feud—one of the most compelling and dramatic in sporting history—pushed the ethical and competitive boundaries of the sport, creating global headlines and defining the spectacle of F1 for a generation.

Cultural Iconography and Legacy

Senna transcended sport in a way few athletes ever have. For Brazilians, he was an ambassador, a symbol of national resilience, discipline, and success in a challenging world. When he won, the nation celebrated collectively, feeling a profound sense of shared achievement. His sudden and tragic death at Imola in 1994 halted the golden age and plunged Brazil into mourning, leaving a void that was both sporting and deeply spiritual. His legacy remains the benchmark against which every succeeding Brazilian driver, and many international drivers, are measured.

A Decade of Depth: Exporting Talent

The success of Piquet and, especially, Senna created a massive surge of interest and financial support for Brazilian junior motorsport, resulting in an unprecedented number of drivers reaching the F1 grid during this period, even if they often found themselves in uncompetitive machinery.

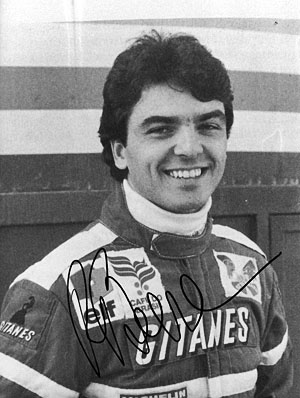

Chico Serra (Debut 1981): Serra’s 18 entries included the distinction of being the final driver

for the original Fittipaldi team before its collapse, underscoring the conclusion of that national

project.

Raul Boesel (Debut 1982): Boesel had stints with March and Ligier. While he did not secure points in F1, his talent was undeniable, and he later established a successful career in American IndyCar and endurance racing, demonstrating the quality of the talent pool.

Roberto Moreno (Debut 1982):

The Super-Sub Moreno holds a special place in F1 lore. Known for his determined sporadic drives across numerous teams (Lotus, Benetton, Forti), his persistence paid off dramatically. He scored a career-defining moment by achieving a stunning, lone podium (2nd place) for Benetton at the 1990 Japanese Grand Prix. This drive proved that when given a competitive car, Moreno possessed the raw speed to perform at the absolute highest level.

Maurício Gugelmin (Debut 1988):

Gugelmin made 74 entries, racing for March and Leyton House. He achieved a memorable milestone by scoring a single podium (3rd place) in his debut season, a significant accomplishment in a field dominated by Senna and Prost.

Christian Fittipaldi (Debut 1992):

The dynasty continued with Christian Fittipaldi, the son of Wilson and nephew of Emerson. Racing for Minardi and Footwork (40 entries), he successfully maintained the family’s presence in F1. He is also famously remembered for a spectacular somersault crash during the 1993 Italian Grand Prix where he emerged unharmed.

The sheer volume of Brazilians driving during the late 80s and early 90s (Serra, Boesel, Moreno, Gugelmin, C. Fittipaldi, Barrichello) illustrates the robustness of the talent pipeline cultivated under the shadow of Senna’s glory. The era was an export boom, solidifying Brazil’s global standing in motorsport far beyond the accomplishments of the champions alone.

Era IV: The Transitional Years – Endurance and Near Misses (2000s–2010s)

Following Senna’s death, Brazil entered a prolonged phase defined by the dedicated presence of veteran drivers who maintained the country’s high representation on the grid, striving relentlessly for the elusive fourth World Championship. This era was characterized by longevity, resilience, and heartbreaking near misses.

Rubens Barrichello (Debut 1993): The Iron Man of F1

Rubens Gonçalves Barrichello debuted with Jordan in 1993, beginning a remarkable career that spanned almost two decades. He raced for seven teams, most notably Ferrari (2000–2005), and later Brawn GP and Williams. Rubens Gonçalves Barrichello debuted with Jordan in 1993, beginning a remarkable career that spanned almost two decades. He raced for seven teams, most notably Ferrari (2000–2005), and later Brawn GP and Williams.

Barrichello’s career is defined by sheer statistical endurance. He holds the Formula 1 record for the most Grand Prix starts (322) and most entries (326), earning him the moniker “The Iron Man of F1”. During his time with Ferrari, alongside Michael Schumacher, Barrichello played a crucial supporting role, contributing to five consecutive World Constructors’ Championships. He also finished runner-up in the World Drivers’ Championship twice (2002 and 2004).

Despite his sustained excellence and 11 career wins, Barrichello never secured the WDC title.

He holds the record for the most podiums for a non-World Champion (68). His success, particularly his maiden victory at the 2000 German Grand Prix, kept the Brazilian flag flying high. Post-F1, Barrichello transitioned seamlessly back to Brazilian motorsport, becoming a two-time champion in the highly competitive Stock Car Pro Series (2014, 2022). Barrichello’s high statistical output but zero WDCs epitomizes the structural challenge of this era: maintaining world-class skill while often occupying a secondary team role behind a dominant teammate.

Felipe Massa (Debut 2002): The Heartbreak of Interlagos

Felipe Massa debuted in 2002 with Sauber, eventually earning a coveted seat at Ferrari (2006–2013) before finishing his career with Williams. Massa accumulated 11 wins and 41 podiums during his 269 starts.

A key achievement for Massa was becoming the first Brazilian driver since Ayrton Senna to win his home Grand Prix in 2006. He repeated this feat later in his career, further cementing his popularity at Interlagos.

The Tragedy of 2008

Massa’s career is most dramatically defined by the outcome of the 2008 World Drivers’ Championship. In what remains arguably the most dramatic title climax in F1 history, Massa won the final race, the Brazilian Grand Prix, and was World Champion for mere seconds, only to lose the title by one point to Lewis Hamilton on the last corner of the last lap.

This heartbreak was compounded by later revelations regarding the 2008 Singapore Grand Prix (Crashgate), an incident of race-fixing that allegedly impacted the championship outcome. Massa is currently pursuing legal action against the FIA regarding the results of the 2008 championship, a fact that underlines how deeply the quest for a fourth Brazilian title remains entangled with unresolved issues of sporting integrity and fairness.

Massa also endured a life-threatening injury during the 2009 Hungarian Grand Prix qualifying when debris struck his helmet at high speed, highlighting the immense physical and mental resilience required to compete at this level. Like Barrichello, Massa transitioned successfully to Formula E and the Brazilian Stock Car Pro Series post-F1.

The Millennial Generation: High Volume, High Hopes

The 2000s saw a large number of Brazilian drivers enter F1, continuing the tradition of exporting talent, often with substantial backing, but rarely with the opportunity for front-running success.

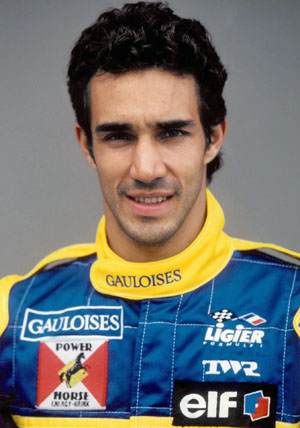

Pedro Diniz (Debut 1995):

Diniz had 98 entries across Forti, Ligier, Arrows, and Sauber. His presence was largely notable for the substantial sponsorship packages he brought to the

midfield teams.

Ricardo Rosset (Debut 1996):

Rosset participated in 26 races, including being part of the

ill-fated Lola project in 1997.

Tarso Marques (Debut 1996):

Marques had sporadic stints with Minardi over multiple years (24 entries).

Ricardo Zonta (Debut 1999):

Zonta raced for BAR and Jordan, with a total of 36 entries. He

maintained a presence in motorsport through subsequent test and reserve driver roles.

Luciano Burti (Debut 2000):

Burti’s promising career, encompassing drives for Jaguar and

Prost, was tragically interrupted by two severe accidents in 2001, forcing a premature end to

his F1 efforts.

Enrique Bernoldi (Debut 2001):

Bernoldi raced for Arrows (28 entries), known for his

aggressive, spirited driving style in the highly competitive midfield.

Cristiano da Matta (Debut 2003):

An accomplished ex-CART champion, da Matta struggled

to translate his American open-wheel speed to success during his two years with Toyota.

Antônio Pizzonia (Debut 2003):

Pizzonia gained experience during sporadic replacement

drives for Jaguar and Williams (20 entries).

The depth of participation in this era demonstrates that the core skill set of Brazilian motorsport remained world-class, but the structural opportunity to achieve ultimate championship success was limited, resulting in high output but a WDC drought.

Era V: The Modern Generation – The Search for the Next Champion (2010s–Present)

The most recent era of Brazilian F1 drivers is defined by the persistence of dynastic names

and a renewed effort to break back into the top echelons of a more streamlined, professionalized F1 environment.

Legacy and Transition

Nelson Piquet Jr. (Debut 2008):

The son of Nelson Piquet, Nelsinho Piquet drove for Renault, scoring one podium finish. His legacy, however, became tragically linked to the infamous “Crashgate” scandal at the 2008 Singapore Grand Prix, where he was instructed to crash deliberately—a controversy that defined his short F1 career.

Bruno Senna (Debut 2010):

Carrying the immense weight of his uncle Ayrton’s name, Bruno Senna successfully reached F1, driving for HRT, Lotus, and Williams. His 46 entries ensured the iconic Senna name remained present on the grid, symbolizing the dynastic commitment to the sport.

Lucas di Grassi (Debut 2010):

After a single season with Virgin (18 entries), di Grassi demonstrated significant adaptability, transitioning to become a highly successful pioneer and champion in the nascent Formula E series, proving Brazilian talent can dominate new

electric formulas.

The Recent Presence

Felipe Nasr (Debut 2015): Nasr raced for Sauber (39 entries). His career defining moment came at the 2016 Brazilian Grand Prix, where he scored critical points for Sauber. These points proved essential, providing the financial stability necessary for the team’s continued existence, showcasing the direct, tangible impact Brazilian drivers can have even in the lower midfield.

Pietro Fittipaldi (Debut 2020): Pietro, the grandson of Emerson Fittipaldi, debuted for Haas in 2020, continuing the Fittipaldi dynasty into its third generation. This persistence highlights the powerful dynastic nature of Brazilian motorsport, where family legacy ensures continuous national media and sponsorship interest.

Gabriel Bortoleto (2025 Debut): The Future Hope

After nearly a decade without a full-time, front-running Brazilian prospect, the nation looks

toward Gabriel Bortoleto. Born in São Paulo, Bortoleto represents the current culmination of

the meritocratic feeder series structure.

Bortoleto enters F1 in 2025 with Sauber (Kick Sauber, which will transition to the Audi factory

team). His position is not predicated on legacy or sporadic drives but on systematic

dominance, having secured the FIA F3 Championship in 2023 and the FIA F2

Championship in 2024.

Crucially, Bortoleto is managed by Fernando Alonso’s A14 agency and has signed a multi-year

deal with Sauber. This strategic positioning signifies that the international market views

Bortoleto as a stable, long-term investment for a future manufacturer project (Audi in 2026).

His arrival represents a clean slate, offering the potential to break the current WDC drought, a

structured attempt to recapture the dominance enjoyed by Fittipaldi and Piquet decades ago.

Comparative Analysis: The Pantheon of Champions

The three Brazilian World Champions—Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson Piquet, and Ayrton Senna—not only defined their respective eras but represent three distinct approaches to speed, strategy, and race management.

Fittipaldi vs. Piquet vs. Senna: Stylistic Differences

Champion | Signature Style | Era Mastered | Psychological Profile |

Emerson Fittipaldi | Smooth precision, excellent feel for tire limits. | 1970s: Shift to wing cars and sponsor-driven teams. | The ‘Golden Boy’—intuitive, pioneering, charismatic. |

Nelson Piquet | Meticulous technical setup, tire management, strategy. | 1980s: Turbocharging, ground effects, and radical engineering. | The ‘Pragmatic Engineer’—calculating, highly adaptive, disciplined. |

Ayrton Senna | Sheer commitment, legendary wet-weather pace, late braking. | Late 1980s/Early 1990s: High-downforce, electronic aids, V10 power. | The ‘Intense Artist’—uncompromising, spiritual, single-minded. |

Emerson Fittipaldi was the pioneer who proved success was possible. His driving was characterized by the ability to blend smooth lines with aggression, using his “amazing anticipation, coordination, and reflex” to extract performance from the temperamental, early ground-effect cars. He achieved success across different car generations, thriving in the shift from Lotus’s experimental designs to McLaren’s organized professionalism.

Nelson Piquet represented a mastery of engineering. His titles in 1981, 1983, and 1987 saw him navigate the most rapid period of technological change F1 has ever seen. He was less reliant on raw emotional speed and more focused on meticulous feedback and setup. This focus allowed him to master the complex, volatile nature of early turbo engines and radical chassis designs, such as the Brabham BT52 with its revolutionary design elements. His success was technical, grounded in meticulous preparation.

Ayrton Senna redefined intensity. His speed often seemed supernatural, particularly in the

rain. Senna’s brilliance lay in his ability to push beyond the apparent limits of the car and human endurance. He dominated the high-downforce, electronic era, mastering the complex systems and exploiting the V10 engines of the late 80s and early 90s. His success was not just technical but deeply psychological; his relentless commitment pushed rivals, most notably Prost, to their breaking points.

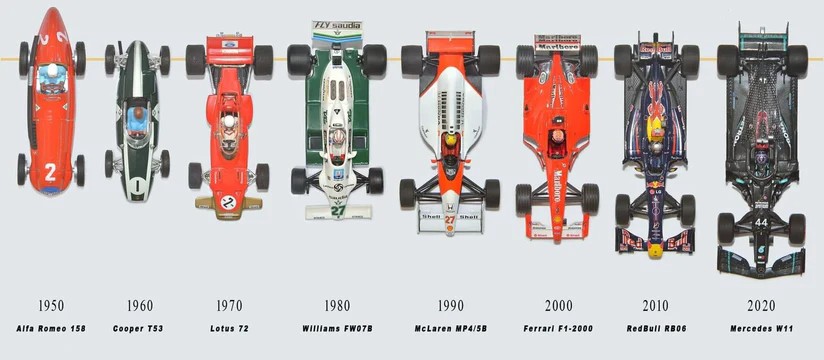

Correlation with Technological Revolutions

The historical success of the Brazilian champions is remarkably correlated with the most significant technological revolutions in F1 history. Fittipaldi broke through during the shift to standardized professionalism and sponsor-driven teams. Piquet mastered the switch to turbocharging and radical ground effects, necessitating a new level of engineering partnership. Senna dominated the high-downforce, electronic era. This correlation demonstrates a crucial characteristic of Brazilian driving ethos: a capacity for daring, fluid, and rapid adaptation to technically demanding machinery, allowing them to extract peak performance when the rules or technology radically shifted.

Brazil's Importance in F1’s Global Popularity

The collective dominance of these three champions across three decades solidified F1’s global profile, especially in South America. Senna’s iconic status, in particular, transcended mere racing, making F1 accessible and compelling to a massive, passionate global audience. The narrative established by these champions—of daring speed, dramatic rivalries, and national pride—is central to F1’s global cultural narrative.

Legacy Beyond the Cockpit: Brazil’s Enduring F1 Influence

Brazil’s contribution to Formula 1 extends far beyond the collective 101 victories and 33 drivers. The nation has provided critical infrastructure, cultural depth, and a self-sustaining dynastic structure that ensures its influence remains profound.

The Soul of Interlagos: Autódromo José Carlos Pace

The Autódromo José Carlos Pace, universally known as Interlagos, serves as the symbolic heart of Brazilian motorsport. Officially named after the 1975 race winner, the circuit is nestled “between two large reservoirs” on the outskirts of São Paulo.

The track is revered by drivers and fans alike for its challenging, “old-school layout and electric atmosphere”. Its distinct features, including dramatic elevation changes and the legendary “Senna S” at Turn 1, demand absolute commitment and skill. The notoriously unpredictable São Paulo weather frequently adds an “extra layer of excitement,” often making the Brazilian Grand Prix one of the most dramatic and title-deciding events on the calendar.

Interlagos is not merely a venue; it is a cultural crucible where national identity and sporting drama converge. The city of São Paulo, a massive melting pot of cultures, pulses with a vibrant, carnival-like energy that infects the race weekend. This potent combination of demanding racing and fan fervor ensures Interlagos remains a non-negotiable anchor for the World Championship schedule. The continuous enthusiasm for this event demonstrates that the passion for F1 is culturally embedded, guaranteeing a captive, engaged audience for future generations of Brazilian talent.

The Dynastic Structure and Talent Pipeline

One of Brazil’s most unique contributions is the multi-generational family commitment to F1. The continuous involvement of the Fittipaldi family, spanning three generations (Emerson, Wilson, Christian, and Pietro) over half a century, illustrates a profound, almost inherited, dedication to the sport. The return of the Senna name through Bruno further solidified this dynastic presence.

This powerful dynastic structure ensures that the F1 narrative is perpetually sustained within

the nation, fueling continuous media interest, securing sponsorship opportunities, and motivating young talent. While some of these legacy drivers may not have reached the heights of their predecessors, their presence acts as an informal motorsport academy, ensuring that the necessary skills and contacts remain within the national ecosystem, supporting the next crop of drivers like Gabriel Bortoleto.

Post-Retirement Influence and Global Reach

Brazilian drivers have also been instrumental in elevating other areas of global motorsport

post-F1.

American Open-Wheel Success: Following his F1 career, Emerson Fittipaldi achieved massive success in American open-wheel racing, winning the 1989 CART title and becoming a two-time winner of the Indianapolis 500 (1989, 1993). This success helped bridge the transatlantic divide, popularizing American racing globally and showcasing the versatility of Brazilian talent.

National Motorsport Elevation: The return of veterans like Rubens Barrichello and Felipe

Massa to the Stock Car Pro Series has significantly elevated the profile and competitiveness

of Brazilian national motorsport. Barrichello’s two titles in the series demonstrate that top-tier

driving talent continues to circulate within the country, maintaining high standards for the

domestic racing ladder.

New Racing Formulas: Lucas di Grassi’s rapid transition and championship success in Formula E exemplify Brazilian adaptability in new, rapidly evolving technological series. This

suggests that the core skill—extracting performance from highly specific, technically demanding machinery—remains a hallmark of Brazilian driving, just as it was for Piquet in the 1980s.

Timeline Summary Table

The following table provides a comprehensive overview of every Brazilian driver who has participated in the Formula 1 World Championship, from the 1950s pioneers to the modern prospects, summarizing their vital statistics and enduring significance. Timeline Summary of Every Brazilian F1 Driver.

Driver Name | Debut Year | Active Years | Teams | Races / Wins / Podiums / Titles | One-Line Legacy Note |

1951 | 1951–1953, 1956 | Maserati, Ferrari (Privateer) | 6 / 0 / 0 / 0 | The undisputed pioneer and first point scorer for Brazil. | |

1952 | 1952 | Maserati | 3 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Early participant in the Escuderia Bandeirantes era. | |

1955 | 1955–1956 | Gordini | 7 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Mid-fifties entrant who achieved a best finish of 8th. | |

1959 | 1959 | Tec-Mec, Scuderia Centro Sud | 3 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Early participant whose career was curtailed by injury. | |

1970 | 1970–1980 | Lotus, McLaren, Fittipaldi | 144 / 14 / 35 / 2 | Brazil’s first World Champion and F1’s “Golden Boy”. | |

1972 | 1972–1975 | Brabham, Fittipaldi | 35 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Brother of Emerson and founder of the Brazilian Copersucar team. | |

1972 | 1972–1977 | Surtees, Brabham | 72 / 1 / 6 / 0 | Immortalized by his single home GP win; the Interlagos circuit namesake. | |

1973 | 1973 | Surtees | 1 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Only started his home Grand Prix in 1973. | |

1976 | 1976–1977 | Fittipaldi | 6 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Known for success in Brazilian Stock Car racing post-F1. | |

1976 | 1976–1977, 1979 | Hesketh, March, Fittipaldi | 20 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Consistent, though mostly uncompetitive, privateer entrant. | |

1978 | 1978–1991 | Brabham, Williams, Lotus, Benetton | 204 / 23 / 60 / 3 | The calculating strategist who mastered the turbo era with three WDCs. | |

1981 | 1981–1983 | Fittipaldi, Arrows | 18 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Final driver for the Fittipaldi team before its collapse. | |

1982 | 1982–1983, 1987 | March, Ligier | 30 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Later found success in endurance and Indy Car racing. | |

1982 | 1982, 1987, 1989–1992, 1995 | Benetton, Jordan, Forti | 42 / 0 / 1 / 0 | Known as the “Super-Sub” with a surprising Benetton podium. | |

1984 | 1984–1994 | 161 / 41 / 80 / 3 | The legendary “Magic Senna,” known for intense skill and dedication. | ||

1988 | 1988–1992 | March, Leyton House, Jordan | 74 / 0 / 1 / 0 | Scored a memorable third-place podium in his debut season. | |

1992 | 1992–1994 | Minardi, Footwork | 40 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Son of Wilson, notable for F1 and later successful CART career. | |

1993 | 1993–2011 | Ferrari, Brawn, Williams | 322 / 11 / 68 / 0 | The Iron Man: F1 record holder for most starts and non-champion podiums. | |

1995 | 1995–2000 | Forti, Ligier, Arrows, Sauber | 98 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Note worthy primarily for his consistent sponsorship support. | |

1996 | 1996–1998 | Footwork, Lola, Tyrrell | 26 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Part of the doomed Lola project in 1997. | |

1996 | 1996–1997, 2001 | Minardi | 24 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Had multiple short stints with Minardi. | |

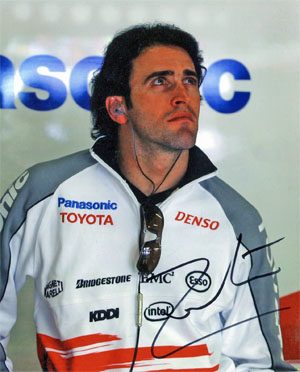

1999 | 1999–2001, 2004–2005 | BAR, Jordan, Toyota | 36 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Known for sports car racing successes alongside F1 reserve roles. | |

2000 | 2000–2001 | Jaguar, Prost | 15 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Career tragically cut short by two major accidents in 2001. | |

2001 | 2001–2002 | Arrows | 28 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Known for his fierce, short-lived midfield battles. | |

2002 | 2002, 2004–2017 | Sauber, Ferrari, Williams | 269 / 11 / 41 / 0 | The face of the 2000s, tragically losing the 2008 title by one point. | |

2003 | 2003–2004 | Toyota | 28 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Ex-CART champion who struggled to translate speed to F1 success. | |

2003 | 2003–2005 | Jaguar, Williams | 20 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Known for sporadic replacement drives at Williams. | |

2008 | 2008–2009 | Renault | 28 / 0 / 1 / 0 | Son of Nelson Piquet, infamous for the “Crashgate” controversy. | |

2010 | 2010–2012 | HRT, Lotus, Williams | 46 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Nephew of Ayrton, carrying the iconic name into the modern era. | |

2010 | 2010 | Virgin | 18 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Later became a champion and fixture in Formula E. | |

2015 | 2015–2016 | 39 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Scored vital points for Sauber at the 2016 Brazilian Grand Prix. | ||

2020 | 2020 | 2 / 0 / 0 / 0 | Grandson of Emerson, maintaining the Fittipaldi name in F1. | ||

2025 | 2025– | 20 / 0 / 0 / 0 | F2 and F3 champion, representing the current hope for a Brazilian revival. |

The Undying Flame of Brazilian Motorsport

Brazil’s Formula 1 legacy is one of unparalleled passion, marked by periods of soaring triumph and profound heartache. The journey, spanning more than seven decades, began with the struggle of Chico Landi to achieve 1.5 shared points in 1956, and culminated in a collective total of 101 victories and eight World Drivers’ Championships.

This heritage demonstrates that success in F1 for Brazilian drivers has never been guaranteed; it has been earned through sheer force of will, technical adaptability, and an emotional connection to the sport that few nations can rival. From Emerson Fittipaldi’s pioneering youth and Nelson Piquet’s calculating pragmatism to Ayrton Senna’s transcendental intensity, Brazil has produced drivers uniquely capable of mastering the technological and psychological demands of F1 across every major era.

Even during the transitional years, the endurance of Rubens Barrichello—the sport’s most experienced driver and the non-champion with the most podiums —and the tragic near-miss of Felipe Massa in 2008 kept the flame of championship aspiration alive. These careers illustrate that the core Brazilian skill level remained world-class, even when structural opportunities for titles were limited.

The symbolic heart of this passion remains Interlagos, the Autódromo José Carlos Pace, where the vibrant, carnival atmosphere of São Paulo guarantees a spectacle beloved by fans and drivers alike.

Today, Brazil stands on the cusp of a new era. The ascent of Gabriel Bortoleto, entering F1 in 2025 as a reigning F2 and F3 champion with a multi-year deal backing the future Audi factory effort, signals a return to a highly structured and meritocratic path to the top. Bortoleto carries the torch passed down from the three champions, representing the hope that the golden era can return.Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The history of Brazilian Formula 1 drivers is a testament to the fact that talent and tenacity can overcome resource gaps and historical challenges. The enduring pride, the vibrant colors of the national flag in the stands, and the collective memory of Magic Senna ensure that Brazilian motorsport will continue to inspire the next generation, eager to write the next victorious chapter in F1 history.Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The subsequent time I read a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I imply, I do know it was my choice to read, but I truly thought youd have one thing interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about one thing that you may repair in the event you werent too busy in search of attention.